A new 2,600m2 park is coming to 229 Richmond St. W. The site is currently leased to a restaurant and used as an outdoor patio. Waawaatesi, the proposed design by West 8 Urban Design and Landscape Architecture and team has been selected as the winning design through a two-stage design competition.

While we aim to provide fully accessible content, there is no text alternative available for some of the content on this site. If you require alternate formats or need assistance understanding our maps, drawings, or any other content, please contact Lara Herald at 416-394-5723.

The timeline is subject to change.

This project has been classified as a Collaborate project based on the International Association of Public Participation Spectrum. This means we aim to partner with the public, stakeholders and rightsholders in each aspect of the design process, including the development of design options and the identification of a preferred design.

Waawaatesi (Firefly in Anishinaabemowin) was selected from the shortlisted designs as the winning design by a jury of experts in landscape architecture, architecture, urban design, art, curation, climate resilience, and Indigenous design. The Jury’s decision was based in part on the public’s feedback, as well as each proposed design’s ability to meet the evaluation criteria and technical requirements identified by the City.

Read the full Jury Report.

Over the next two years, the proposed design will be refined into a final detailed design. Additional opportunities for public engagement, including selecting a permanent name for the new park, will occur in advance of construction.

Waawaatesi is a park with a night life and a winter attitude, who is not afraid to share silenced stories and urgent agendas. In a place where skyscrapers have eaten up the city, Waawaatesi becomes the compass, lighting the trail to renewal and transformation. She is the boutique and alternative backstage platform of Toronto’s Downtown Arts district: an authentic place for people of all walks of life to discover unique integrated experiences of landscape, light, and performance. Waawaatesi will be Toronto’s first park with a curator and her own tailored calendar of arts events and installations. This is a place where traditional myths are given contemporary mediums.

Waawaatesi (Anishinaabemowin: firefly) symbolizes the cycle of life, healing, and the passage of time. Along with the creek that used to cross the site who was buried by Toronto’s rapid urbanization, fireflies have all but disappeared from the urban landscape. Her name calls attention to the power of the unseen and supernatural.

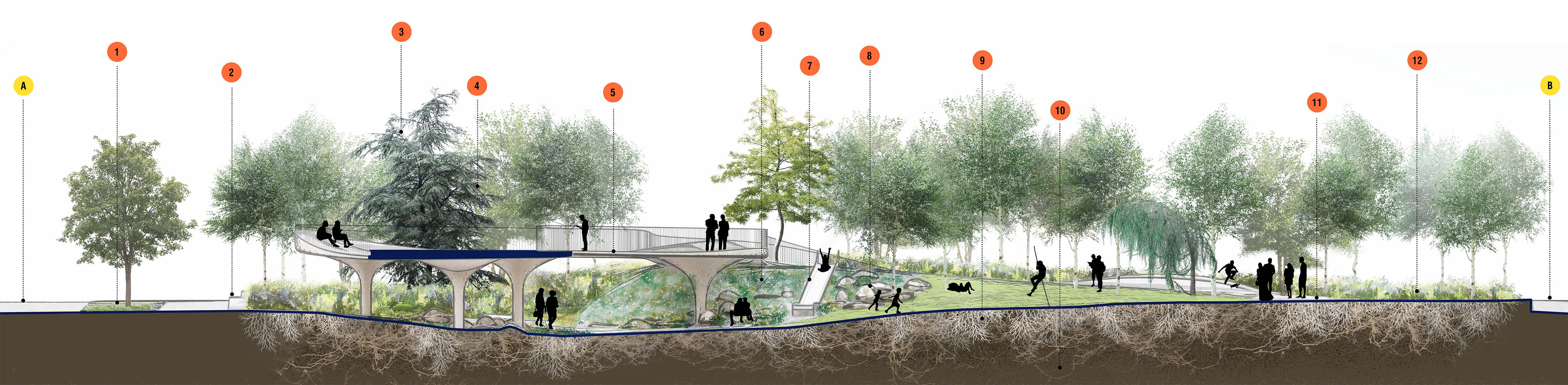

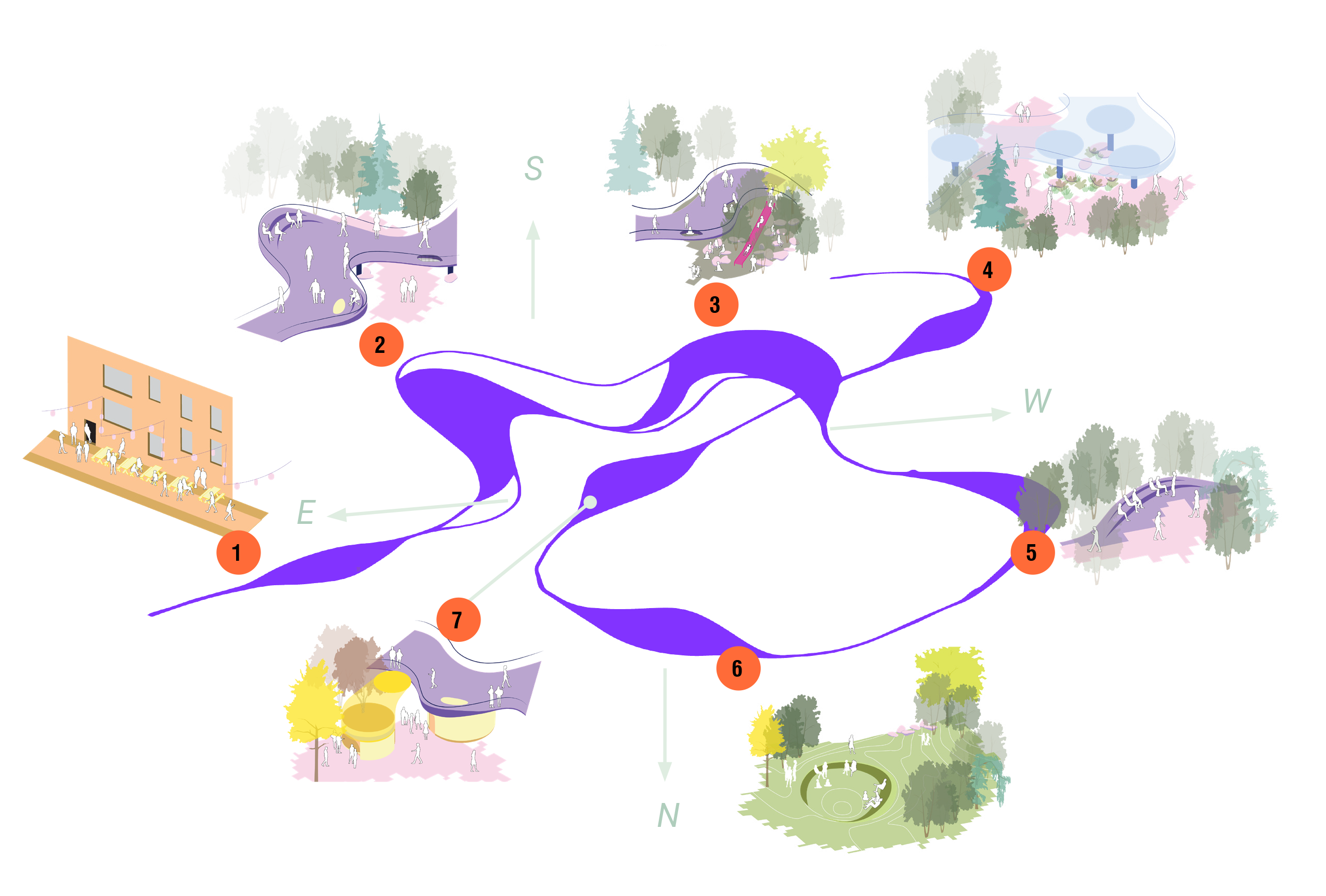

Waawaatesi invites you to enter a multi-level journey through the woodlands from each of the four directions, as actor and audience in the theatre of life. A stream-like trail leads you along seven stepping stones with different experiential qualities. The Eastern Gateway – humane laneway and park welcome, The Balcony – place to watch and perform, The Riverbed Playscape – with hammocks and slide, The Grove – for fireflies, The Green – to gather, The Source – of water and light, and The Canvas – for light. Her seasonally shape-shifting art piece Aki Illuminations (Anishinaabemowin: Earth Illuminations) celebrates solstice, equinox, and transformation.

In Waawaatesi, a stream-like trail leads you along seven stepping stones corresponding to different park program elements, each with their own experiential quality.

The path and its winding through the changing experiences, seasons, and sounds of an urban park area metaphor for life: constantly in transformation, whether it be through the colour of the trees or the sounds of children or decay of leaves.

In the tradition of landscape architecture, parks and gardens are illusions of reality. The changing of seasons; the cycles of life. The teaching of the Seven Stepping Stones shared with us by elder Shelley Charles (Mandawke) brings depth and layers to outdoor public culture.

The teaching shares the story of people who have lost their way and in need of guidance. The searchers look along the water for seven stepping stones to help find their way back to the trail where there is food, water, and community. While this teaching refers to a specific sacred place, when applied to Waawaatesi, it teaches us to never go too far off the path without coming together as humans. This teaching also reminds us of the power of water to shape, even where water is unseen.

Between January and September 2023, the City held a two-stage design competition for the design of the new park at 229 Richmond St. W.

The two-stage design competition was open to design teams, including international talent, and had to include a Landscape Architect in good standing with the Ontario Association of Landscape Architects. The first stage of the competition was a Request for Supplier Qualifications (RFSQ). The applicants were evaluated by an evaluation committee based on their qualifications, work experience, and approach to the park site.

The five highest-rated teams were shortlisted and invited to participate in Stage Two of the competition. These teams were:

In the second stage of the competition, the shortlisted applicants responded to a Request for Proposals (RFP) and submitted conceptual designs for the new park. Applicants presented their design ideas to the Design Jury made up of experts in landscape architecture, architecture, urban design, art, curation, climate resilience and Indigenous design.

The two-stage design competition was open to design teams, including international talent. Each team was led by a Landscape Architect in good standing with the Ontario Association of Landscape Architects. The teams also included:

In this stage, the City collected applications from eligible design teams. The applicants were evaluated based on their qualifications, work experience, and approach to the park site.

Stage One RFSQ submissions were reviewed by an Evaluation Committee made up of City Staff and the Professional Advisor to the Design Competition. The five highest-rated teams will be shortlisted and invited to participate in Stage Two. Each shortlisted team received an honorarium of $10,000.

The application submission deadline closed on March 23, 2023 at 12 p.m. EST.

In this stage, the shortlisted applicants submitted conceptual designs for the new park. The applicants received a competition brief in the form of a Request for Proposals (RFP), which outlined the submission requirements and provided additional material required to develop the designs. This stage included an orientation session and a site tour.

The shortlisted applicants presented their design ideas to the Design Jury. The design ideas were also shared on this page. A Professional Advisor collected and summarized all feedback on the design ideas from the Community Advisory Group, the Park Steering Committee, and the community. The feedback will inform the Design Jury’s recommendation.

The design competition was judged by a Jury of experts in landscape architecture, architecture, urban design, art, curation, climate resilience and Indigenous design. Adjudication took place in November 2023. The Jury was:

The following designs were shortlisted and considered by the jury but were ultimately not selected.

This is the Electric Forest. In Anishinaabemowin, Waasamoo-mitigoog means electric forest/trees. Throughout the design, our Indigenous Placekeeper led us through teachings about the history of pine and cedar and their importance to this land and its people. The Eastern White Cedar has medicinal and spiritual significance, symbolizing strength and resilience. The Eastern White Pine has deep connections to Treaty 13 and is known in Haudenosaunee as “the tree of peace”. The park’s dominant curvaceous forms take their cues from these trees.

The name also alludes to Electric Circus, the unscripted and kinetically vibrant MuchMusic show. MuchMusic, the Canadian institution that sparked energy and defined a spirit of belonging and open-minded culture-making in this neighbourhood for decades, was a generation’s natural cultural lab. As the park’s name conjures up the spirit of curiosity and experimentation that was MuchMusic, it integrates this with a powerful meditation about land and regeneration. The park is to be a place electrified by charged histories and the regenerative power – mentally, psychologically, and ecologically – of a forest.

If this proposal is about regenerating living environments, it also strives to do so playfully and without austerity. Joy, contemplation, awe, and delight are foremost in our mind. A little bit nature; a little bit culture; and every bit wild, this park is designed as an energy source in the city. With the power of the ancestral forests and the vibrancy of MuchMusic all but turned off from the Queen and John neighbourhood, Waasamoo-mitigoog/Electric Forest is a playful reignition of a public place in our city.

oneSky Park/Bezhig Giizhig (in Anishinaabe) – “we all see it there, one sky.”

The new park at 229 Richmond St. W. faces the challenge of creating a park amidst a rapidly changing area. Situated in a mid-block of downtown, it is close to bustling streets and major attractions, yet surrounded by a neighbourhood undergoing substantial transformation.

While these changes are anticipated in a thriving city, they pose day-to-day difficulties for community members seeking an engaging outdoor environment connected to nature. In this dynamic setting, how can equilibrium be established? Where is the common ground that unites us?

The sky provides a universal connection. We all share the same celestial view, experiencing the same moon, sun, and stars. The sky is a constant presence, regardless of alterations in our tangible surroundings, symbolizing our shared human experience.

oneSKY embodies these collective insights: encompassing land and sky, water and wind, with clarity and purpose. It serves as a beacon of unity and harmony in a changing urban landscape.

The vision for this urban transformation is to seamlessly blend nature with urban living and use all the great qualities that the site contains today.

The three key goals of our oneSKY vision is to:

Our park design proposal aims to breathe new life into an old parking lot, ensuring that it not only becomes a lush park but is also future-proofed for generations to come.

Imagine a lush verdant garden in the heart of the city. Imagine it is nestled within a large, sculpted landform – an open palm sculpted in stone. The hand symbolizes the animism of the earth. In cradling the garden, it guides us to care for nature.

It is called Nookomis for this sense of caring guidance. In some Anishnaabe origin stories Nookomis fell from the moon to the earth and gave birth to the mother of the Anishnaabe people. Also associated with the moon, Nookomis is connected to all life on earth, and her gentle hand has long guided the Anishnaabe people in the cycles of life including planting, harvesting, hunting, gathering and ceremony.

Nookomis literally translates as “my grandmother.” The teachings of our grandparents occupy a privileged place in society.

Nookomis Garden is a physical manifestation of the gifts we are offered by the natural world – the stone of the earth, the waters, the soil and the plants that nourish us. Cradled within the hand, these features come together into a lush, dense forest planting. The surrounding mounds carry plantings found within the oak woodland native to these lands.

Nookomis Garden is meant as a meditation on “how to live the good life.” It is a place connected to its surroundings and accommodating of larger crowds, while offering opportunities for quiet contemplation in nature. It is a place for gathering, sharing stories, and honouring the gifts offered by the natural world.

Narratives are powerful tools that shape memory, influence values, and drive behaviour. River Park is centred around reimagining the narrative of urban parks to transform relationships between people and nature in a time when such a shift is urgently needed. The park restores the connection between the city and its natural water systems, paying homage to a lost creek, paved over in the 19th century. The design is guided by three core gestures: tracing the path of the river, lifting the edges to create banks, and connecting the city along the edges. The river, flowing through the park, serves as both a subtle topographic change and an ephemeral water feature, emphasizing the importance of water in the urban landscape. The edges offer spaces for daily life and events, including a pavilion, canopy, stage, and a tilted lawn. Tree-lined corridors connect the park to the city, drawing in adjacent activities and reflecting the character of surrounding buildings. The spectacular sculpture, Resurgences, creates a magnificent and startling gateway off Richmond Street as a monument to the city’s lost rivers.

In proposing the name River Park, we seek to shift the narrative surrounding our relationship with nature and each other. This naming process presents an opportunity to connect with the generational history of this area and its evolution, learn about the building practices and decisions that have led to the present, and instill an optimistic view of the future. We envision River Park as a place for reflection, storytelling, and cultural exchange, fostering inclusivity and equity.

This project has a Community Advisory Committee (CAC) made up of representatives of the Spadina-Fort York area. The CAC’s mandate is to provide a forum for feedback, guidance and advice to the project team at key decision points during the community engagement process. The CAC will meet approximately six times throughout the project. The CAC is not a decision-making group and does not speak on behalf of the entire community.

This project has an Indigenous Advisory Circle (IAC) made up of representatives of the city’s Urban Indigenous population. The IAC’s goal is to inform Indigenous Placemaking opportunities and provide feedback and guidance on the overall design for the new park. The IAC will meet three times during Community Engagement Phase 3. The IAC is not a decision-making group and does not speak on behalf of the entire Spadina-Fort York community or the city’s Urban Indigenous population.

The park goals were developed in this phase of the community engagement process using the outcomes of a visioning survey that engaged over 3,000 participants, Community Advisory Group feedback and an internal City stakeholder group meeting. The park goals will guide the park design development.

Eight park goals were developed using the feedback collected during this phase.

The park’s location in the heart of the Entertainment District should provide inspiration for the program and design. The design should reflect and enhance the neighbourhood’s cultural scenes by providing flexible spaces that can support cultural programming. During design development, the design team will continue to consult with the local arts community to determine future programming needs.

The park should be responsive to the adjacent urban context and should draw on the rich cultural and built heritage of the neighbourhood, including the area’s manufacturing history and days as a hub of youth and club culture.

The park should be an oasis and a peaceful green “backyard” for the many downtown residents.

As part of the City’s Reconciliation Action Plan, the park design should incorporate Indigenous knowledge, world views and language(s). The park program should be responsive to the needs of urban Indigenous people for safe places to engage in ceremony, gather and heal. Indigenous people must be included on the design team.

Innovation and artistry should inform the design holistically. A public artist or collective must be included on the design team.

Provide a high standard of design excellence, quality of place and attention to detail. High-quality durable materials, innovative technologies and design excellence should be combined with careful attention to the City’s operating parameters.

The park should set new standards for sustainability in park design and operations by using the lens of net-zero, climate resilience and material life-cycle analysis at all stages of the design. This park should strive to reach the City’s goal of net zero by 2040.

Toronto has one of the most diverse urban populations in the world and the park should support social activities for a wide range of people, groups and civic organizations, including unhoused people. The Entertainment District is a mixed-use neighbourhood, where increasing numbers of residents live among offices, entertainment venues, retail and dining.

From September 18 to September 27, those who identify as Indigenous to Canada could apply to be a member of the Indigenous Advisory Circle (IAC). The IAC received fewer applicants than the project team originally expected. As a result, the IAC will be formed during Phase 3 of the engagement process.

Eight park goals were developed using the outcomes of the feedback collected during this phase of the community engagement process.

On January 9, the Community Advisory Committee had their second meeting.

From September 28 to November 4, the community shared their vision and ideas for the new park and rated the ideas of others in a thought exchange activity. The activity had 3,303 participants, 1,968 thoughts shared and 50,557 ratings.

Download the November 2022 online thought exchange activity summary.

On November 15, the Community Advisory Committee had their first meeting.

In October, a Community Advisory Committee (CAC) was put together, consisting of park experts and working professionals within the surrounding area of the park. Members were invited to help inform the park goals and design competition brief. Community members will be added to the CAC during Phase 3 of the engagement process.

In this phase of the community engagement process, the City will collect community feedback on the shortlisted designs from the two-phase design competition. At the end of this phase, the City will hire a design team.

From October 10 to 29, a survey collected feedback on the shortlisted design submissions for the new park. Participants were asked to evaluate the designs alongside the park design goals and to share their thoughts on each design.

Download the October 2023 survey summary.

In this phase of the community engagement process, the City will present the winning design to the community for feedback and revisions, which will inform the development of a detailed design.

Download the Phase 3 engagement summary.

On December 10, the project team hosted a feast at the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto from 6 to 8 p.m. for members of the Indigenous Advisory Circle, Community Advisory Committee, Technical Advisory Committee and Toronto’s Urban Indigenous population. Participants shared their experiences with the community engagement process.

On December 9, the project team held an open house at Metro Hall from 5 to 8 p.m. to share the updated park designs with community members and provide a final presentation on the park design process.

Download the December 9, 2024 Open House presentation.

On October 30, the project team met with members of the 229 Richmond Community Advisory Committee to gather feedback on the updated park designs.

On September 19, the project team met with members of the Indigenous Advisory Circle to discuss and collect feedback on the Indigenous placemaking elements proposed for the new park, as well as additional park design elements and goals.

From August 29 to September 15, those who identify as Indigenous to Canada could apply to be a member of the Indigenous Advisory Circle (IAC).

On August 19, the project team met with members of the 229 Richmond Community Advisory Committee to discuss and collect feedback on the winning design.

Download the August 19, 2024 Community Advisory Committee meeting minutes.

From May 29 to June 16, community members were invited to apply to the project’s existing Community Advisory Committee (CAC). CAC members will help develop the winning park design.

The site was secured as parkland in 2019 through a transaction involving CreateTO and multiple City Divisions. The transaction resulted in:

Downtown Toronto has one of the lowest parkland provision rates in the city at 5.5m2 per resident (based on the 2016 census) and 1.8m2 per resident and employee. The city-wide average is 28m2 per resident and 18m2 per resident and employee respectively. Nearly 16,000 people live within a 0.5km radius of the new park site, and 52,000 more come to work in this area. This project will create much-needed parkland in a rapidly growing neighbourhood.

A design and construction budget of $10 million has been secured for this project. The new park will be referred to by its location until it is officially named. The park naming process is separate from the park design process.

The future park is located between Richmond Street West to the north and Nelson Street to the south. West of the new park is the future site of a high-rise residential and commercial development at 241 Richmond St. W and 133 John St. with construction starting in 2024. East of the new park are two commercial heritage buildings at 221 Richmond St. W and 30 Duncan St. The site was used as a surface parking lot since the early 1980s. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was leased to local restaurants for summer patio use.

The park site is part of the King-Spadina Heritage Conservation District (HCD), which is an evolved historic district, with a concentration of late-19th and early-20th century residential and commercial buildings, three historic parks and a network of laneways. These historic resources reflect the District’s evolution from an institutional and residential neighbourhood to a warehouse and manufacturing area over the course of the 1880s to 1940s. For the first half of the 20th century, the District was Toronto’s primary manufacturing and warehouse area. After World War II, many industries left the downtown core and relocated to suburban locations.

Subsequent waves of development in the mid to late 20th century saw the regeneration of the District through the adaptive reuse of residential and commercial buildings for a variety of uses. In the 1980s to early 2000s, the area was a mecca for youth culture, as the empty industrial buildings were repurposed as nightclubs and bars. In the last 20 years, a boom of condominiums has transformed the area, creating a mixed-use neighbourhood with offices, bars, restaurants, cultural venues and high-rise residential buildings.