Of the 4,963 Canadians who embarked on the raid, 10 per cent (560) were either born, lived or enlisted in what is now Toronto. More than 144 Toronto residents survived while there were many on the homefront who also supported the war effort as well as families who kept the morale of the prisoners up through letters and care packages.

On the morning of August 19, Captain John Anderson was in charge of a landing craft with over 100 men on board. When it arrived on Puys Beach, the boat was heavily attacked. Thinking quickly, Anderson organized Bren gunners to return fire, even operating a gun himself. When the boat reached the shore, Anderson ensured the landing of all unwounded men as well as a three-inch mortar and its ammunition. Despite being wounded in the head by shell splinters during the initial gunfire, Anderson continued to motivate and direct his men until the end of the raid. He was later evacuated to England.

Captain John Anderson displayed unwavering selflessness by continuing to lead his men despite his own injury. He was later awarded the Military Cross for his bravery.

Stephen Michell and Doreen Cambridge were next door neighbours on Vaughan Road, and their families quickly became fast friends. The Cambridge family moved to England in 1938, but fate would soon bring Stephen and Doreen back together during the Second World War. Stephen enlisted in the Royal Regiment at the start of the war, first training at Fort York, then Iceland and finally arriving in England in 1941. Asked by his uncle who was also a friend, to deliver mail to the Cambridges upon his arrival in England, Stephen and Doreen quickly reconnected with each other. While Stephen prepared for what would be known as the Dieppe Raid, he spent his leave with Doreen who was an active member of the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Corp (CWAC).

Like almost 2,000 of his fellow soldiers, Stephen was taken as a Prisoner of War at the Dieppe Raid. However, he and Doreen continued writing faithfully to each other. During this time, Doreen kept herself busy with the CWACs, rerouting mail to dentists stationed throughout the conflict zones.

Stephen was a member of the camp band, who many years later composed the march “Men of Dieppe” in tribute. Stephen and the band used their music to engage in subversive activities to derail German success. The band even aided in helping 52 men escape, playing loudly to cover up the sound of a tunnel being dug.

Stephen married Doreen in England after he was liberated in 1945. They returned to Toronto and moved to Hastings Avenue before building a home on Havendale Road. Stephen took a job with Canada Post and the couple welcomed four children. In 1958, the family relocated to Huntsville.

Stephen continued to compose music and published two books about his experiences, “They Were Invincible”, published in 1967 and a second, full version, “Profile on Twelve Platoon” published by his son in 2019. He played in the Muskoka District Band well into his golden years.

He played in the Muskoka District Band well into his golden years. He passed away in 1994. Stephen’s march, “Men of Dieppe”, is still played by the Royal Regiment, and other military bands today.

Doreen later becomes Huntsville’s first ever Red Cross Homemaker: a role where women would provide homecare to local families when a parent became ill.

Doreen passed away in 2008 and her husband passed away in 1994. Stephen’s march, “Men of Dieppe”, is still played by the Royal Regiment, and other military bands today.

Following Stephen’s death, his son was was digging through his stack of hand written manuscripts, when he came across an untitled poem written in his father’s hand.

What has happened to the world we once knew?

The world that vibrated with the Warmth of human friendship.

A love of simple things; an old beat-up jalopy, a guitar, the twinkling lights of small towns passed in the moonlight.

In those not-so-far distant days we laughed… loved… and danced to the throbbing beat of drums and keening note of saxophones and strident brass.

With full hearts and empty pockets, we toasted Eros… and were gay.

Then came the call: the bugles blew, and like the fools of every generation, we responded to the sound; aware, as all the world was well aware, a monster had arisen, and must be speedily dispatched… demolished… and interred.

The follies of the fathers must be passed down to the sons, as it has ever been since time in memorial, and therefore we must answer for the folly of Versailles.

In our blood and in the blood of millions upon millions far away, the debt must be repaid.

And as we went… millions of marching feet; each of us wearing bandoliers filled with tiny messengers of death, small, lethal hornets that hum and kill; dispatched from tubes of steel, each one intended for the heart of a brother, far away.

When Cain slew Abel, he was condemned by his kind; Outcast… adrift, a creature to be avoided and abhorred; while we, the product of a higher degree of culture, were dispatched with, love and kisses from our kin, and the blessings, and the prayers of the clergy.

It just shows how much we have advanced in a few thousand years.

Three thousand miles away, our brothers waited for us to arrive so that they could match their powers of annihilation with ours.

There was nothing personal about it; it was just that they were under orders, as were we.

The lies we both were told, were superfluous, just fodder for our consciences. On no account must we be allowed to bear the guilt of having violated the commandment:

Thou shalt not kill; thou shalt not…

During the Second World War, one of the only ways soldiers could keep in touch with their families back home was through letter writing. Sadly, it was also the only way for families to contact the government if their son had gone missing or was confirmed to be killed in action.

Today, these letters serve as riveting, first-hand accounts of a world at war. The following selection of letters are written by or about Torontonians who took part in the Dieppe Raid.

Read on to discover what it felt like to be an active serviceman, a prisoner of war, a civilian, and a family member of a lost loved one.

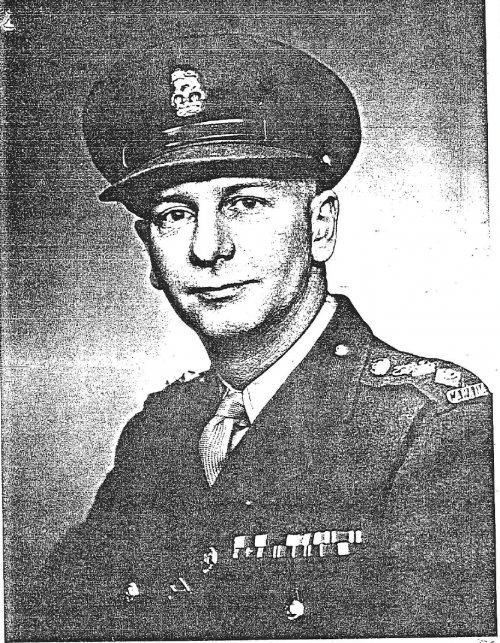

John Graham Housser was born in Toronto in 1914. He attended Upper Canada College and St. Andrew’s College. Prior to enlisting in the army, he worked for the Bank of Nova Scotia and C.T. Financial Services Inc. In 1936, John enlisted in the Royal Grenadiers as a Second Lieutenant, before transferring to the Royal Regiment of Canada in 1938.

When war broke out in 1939, John volunteered for active service, serving in both Iceland and England. On August 19, 1942, Captain Housser embarked on the Dieppe Raid where he was taken Prisoner of War and held at Offlag 7B in Eichstatt, Germany until liberation in 1945. Housser was awarded the Military Cross for his brave leadership at Dieppe.

Upon returning to Toronto following the war, John rejoined the army reserve as served as a Reserve Major in the Royal Regiment. He continued in the army until his retirement as Brigadier General in 1958.

While detained as a POW, John wrote nearly 100 letters back home to his parents and sister, Jane, who lived on Warren Road. His family saved each letter, and they were eventually given to the Ontario Archives by John’s wife.

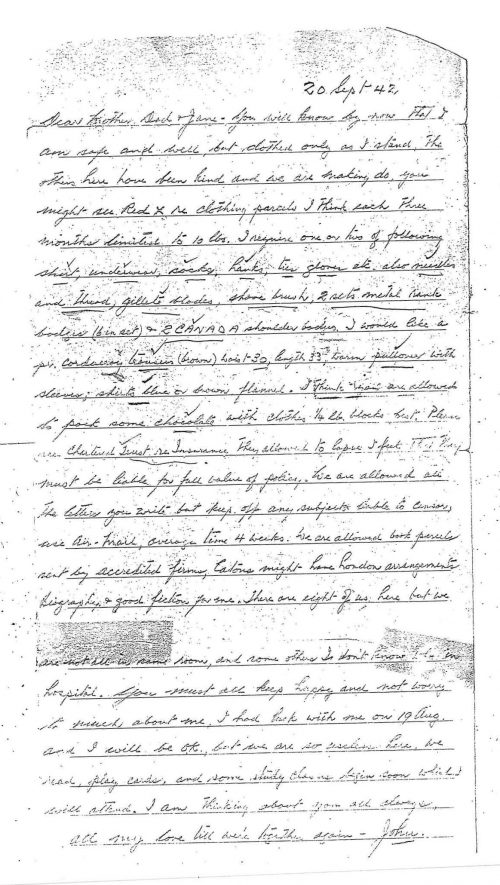

20 Sept. ‘42

Dear Mother, Dad and Jane,

You will know by now that I am safe and well but clothes only as I stand. The others here have been kind and we are making do. You might see Red Cross re clothing parcels. I think each three months limited to 15-10 lbs. I require one or two of the following short, underwear, socks, hanks, ties, gloves, etc. Also needles and thread, Gillette blades, shoe brush, 2 sets of metal rank badges (bin set), and 2 CANADA shoulder badges.

I would like a pair of corduroy trousers (brown) waist 30, length 33, warm pullover, with sleeves; shirts blue or brown flannel. I think you are allowed to pack some chocolate with clothes, ¼ lb blocks best. Please see Charlinch Trust re insurance. They allowed it to lapse. I feel that they must be liable for full value of policy. We are allowed all the letters you write but keep off any subject liable to censor, use Air-Mail, average time 4 weeks. We are allowed book parcels sent by accredited firms, Eatons might have London arrangements Biography and good fiction for me. There are eight of us here but we are all in same room, and some others I don’t know are in hospital. You must all keep happy and not worry too much about me. I had luck with me on 19 Aug and I will be ok, but we are so useless here. We read, play cards, and some study classes beginning, which I will attend. I am thinking about you always.

All my love ‘til we’re together again – John.

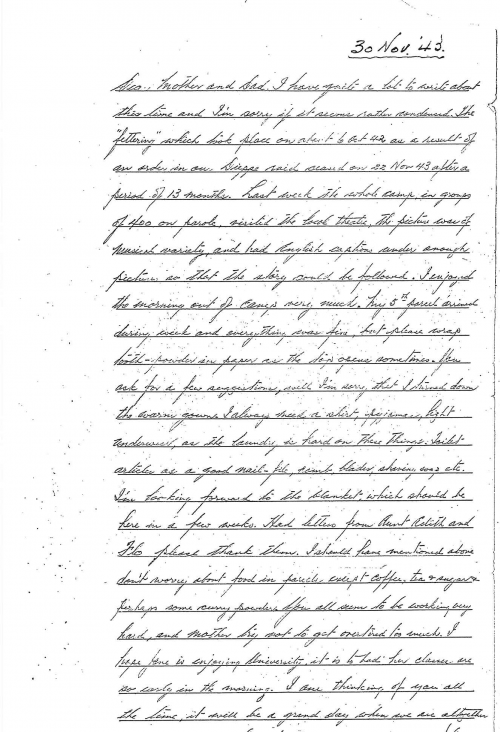

30 Nov. ‘43

Dear Mother and Dad,

I have quite a lot to write about this time and I’m sorry if it seems rather condensed. The “fettering” which took place on about 6 Oct. ’42 as a result of an order in our Dieppe raid ceased on 22 Nov 43 after period of 13 months. Last week the whole, in groups of 400 on parole, visited the local theatre. The picture was of musical variety and had English captions under enough pictures so that the story could be followed. I enjoyed the morning out of camp very much. My 5th parcel arrived during week and everything was fine, but please tooth-powder in paper as the top opens sometimes. You ask for a few suggestions, well I’m sorry that I turned down the warm gown. I always need a shirt, pajamas, light underwear, as the laundry is hard on these things. Toilet articles as a good nail file, comb, blades, shaving soap, etc. I’m looking forward to the blanket, which be here in a few weeks. Had letters from Aunt Edith and Flo please thank them. I should have mentioned above don’t worry about food in parcels except coffee, tea and sugar and perhaps some curry powders. You all seem to be working very hard and Mother try not to get overtired too much. I hope Jane is enjoying University. It is too bad few classes are so early in the morning. I am thinking of you all the time. It will be a great day when we are all together again. Tons of love to you all.

Your son,

John

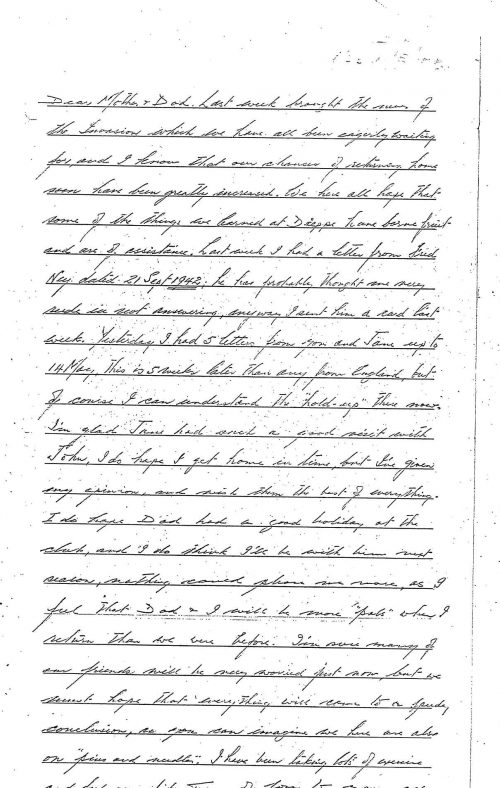

12 June ‘44

Dear Mother and Dad,

Last week brought the news of the invasion which we have all been early waiting for and I know that our chances of returning home soon have been greatly increased. We have all hope that some of the things we learned at Dieppe have become fruit and are of assistance. Last week I had a letter from Jud Ney dated 21 Sept 1942. He has probably thought me very rude in not answering. Anyways, I sent him a card last week. Yesterday I had 5 letters from you Jane up to 14 May. This is 5 weeks later than any from England, but of course I can understand the hold up there now. I’m glad Jane had such a great visit with John. I do hope I get home in time, but I’ve given my opinion and which them the best of everything. I do hope Dad has a great holiday at the club, and I do think I’ll be with him next season. Nothing could please me more, as I feel that Dad and I will be more “pals” when I return than we were before. I’m sure many of our friends will be very worried just now, but we must hope that everything will come to a speedy conclusion, as you can imagine we here are also on “pins and needles.” I have been taking lots of exercise and feel very fit. Tons of love to you all. I think of you constantly.

Your son,

John

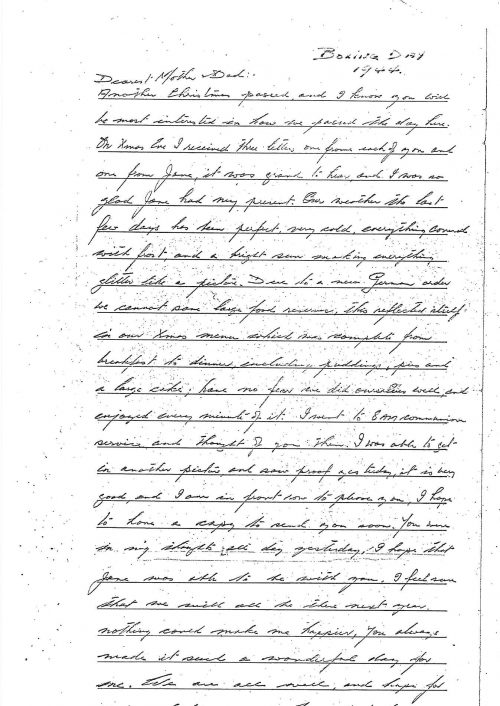

Boxing Day 1944

Dear Mother and Dad,

Another Christmas passed and I know you will be most interested in how we passed the day here. On Xmas Eve I received three letters, one from each of you and one from Jane. It was great to have and I was so glad Jane had my present. Our weather the last few days has been perfect; very cold, everything covered with frost and a bright sun making everything glitter like a picture. Due to a new German order, we cannot save large food reserves. This reflected itself in our Xmas menu which was complete from breakfast to dinner, including, puddings, pies, and a large cake. Have no fear we did ourselves well and enjoyed every minute of it. I went to 8 am communion service and thought of you then. I was able to get in another picture and saw proof of it today. It is very good and I am in front row to please you. I hope to have a cap to send you soon. You were in my thoughts all day yesterday. I hope that Jane was able to be with you. I feel sure that we will all be there next year. Nothing could make me happier. You always make it such a wonderful day for me. We are all well, and hope for some skating soon. My best to everyone but tons and tons of love to yourselves.

Your son,

John

Here are a few other letters:

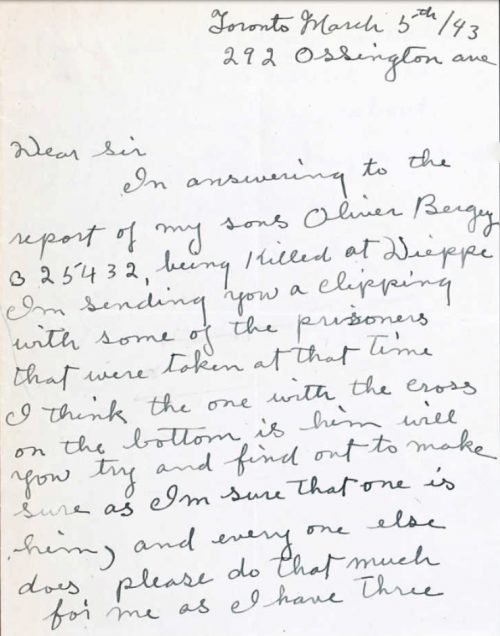

An example of a mother writing to find out the status of her son.

Toronto March 5th/ 43

Dear Sir,

I am answering to the report of my son Oliver Bergey B25432 being killed at Dieppe. I am sending you a clipping with some of the prisoners that were taken at that time. I think the one with the cross on the bottom is him. Will you try and find out to make sure, as I am sure that one is him, and everyone else does. Please do that much for me, as I have three others besides him in active service and I would like to let them know about Oliver, as they keep writing for word of him.

Yours truly,

Mrs. Helen Bergey

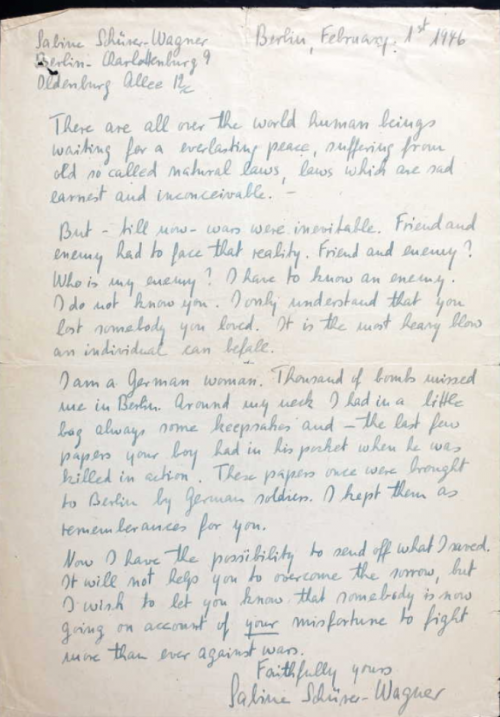

Sabine Schiner-Wagner

Berlin, February 1st, 1946

There are all over the world human beings waiting for everlasting peace, suffering from old so called natural laws, laws with are sad, earnest and inconceivable.

But – ‘til now – wars were inevitable. Friend and enemy had to face that reality. Friend and enemy? Who is my enemy? I have to know an enemy? I do not know you. I only understand that you lost somebody you loved. It is the most heave blow an individual can befall.

I am a German woman. Thousands of bombs missed me in Berlin. Around my neck, I had in a little bag always some keepsakes and – the last few papers your boy had in his pocket when he was killed in action. These papers once were brought to Berlin by German soldiers. I kept them as remembrances for you.

Now I have the possibility to send off what I saved. It will not help you to overcome the sorrow, but I wish to let you know that somebody is now going on account of your misfortune to fight more than ever against wars.

Faithfully yours,

Sabine Schiner-Wagner

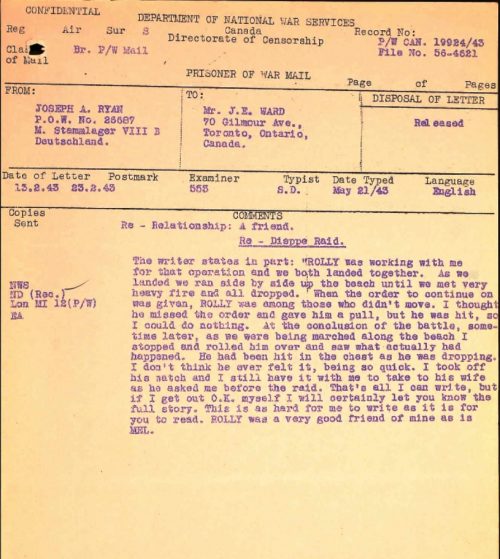

Lance Corporal Ryan, a prisoner of war, wrote to the father of Private Roland Edward Ward, describing how Ward was killed at Dieppe.

TO:

Mr. J.E. Ward

Toronto, ON

13.2.43

“ROLLY was working with me for that operation and we both landed together. As we landed we ran side by side up the beach until we met very heavy fire and all dropped. When the order to continue on was given, ROLLY was among those who didn’t move. I thought he missed the order and gave him a pull, but he was hit, so I could do nothing. At the conclusion of the battle, sometime later, as we were being marched along the beach I stopped and rolled him over and saw what actually had happened. He had been hit in the chest as he was dropping. I don’t think he ever felt it, being so quick. I took off his watch and I still have it with me to take to his wife as he asked me before the raid. That’s all I can write, but if I get out O.K. myself I will certainly let you know the full story….”

Joyce Crook was born on Dillworth Crescent in East York in 1926. After the war started, many young men she grew up with were signing up to go overseas, filling the neighbourhood with uniformed soldiers. At school, Joyce and her classmates participated in making “bundles for Britain,” with each student knitting a seven-inch square that would be sewn into larger blankets for soldiers.

She was 16 years old in 1942 when soldiers landed on Dieppe. She still remembers an afternoon in early September when her mother mentioned a visit from the ice delivery man who told her that his only son had been killed during the Raid. That tragedy, and the tragedies of her neighbours stuck with Joyce over the years.

A decade later, Joyce decided to visit Dieppe on a trip to Europe. Standing on the beach, she could picture the landing crafts carrying the men from her neighbourhood, and many other Canadians to the beaches of Dieppe.