The TTC has a long history of providing services to people with disabilities. In 1926, the Motor Coach Department initiated a service to transport children using wheelchairs. The children were picked up from their homes, wherever they were located in the city, and taken to the Wellesley Street School. By 1930, the number of coaches employed for this purpose had increased from three to four.

In 1948, at the suggestion of the Kiwanis Club of West Toronto, the TTC dedicated one of its buses to be used for moving people who used wheelchairs. The bus was altered by removing the seats and securing blocks to the floor for a wheelchair securement device. The rear door was widened and an access ramp was provided. There was space for eight people using wheelchairs. Prior to this, transport for individuals using wheelchairs often had been provided by ambulances. The first use of this special bus was on January 22, 1948 to transport Second World War veterans for a day trip to the Art Gallery. The veterans were enthusiastic and looked forward to future outings to hockey games and other events.

A different kind of accessibility issue was addressed by a demonstration project called GO Dial-a-Bus, introduced in the fall of 1973. Funded by the Ontario government, but operated by the TTC, the project was devised to address a lack of regular service in certain areas of Metro Toronto that had lower population densities. It was an experiment to see if customers would accept a premium fare, demand-responsive service. The project started with a few mini-vans that could accommodate 11 passengers. The Dial-a-Bus picked passengers up at their door, and delivered them to places such as shopping malls, hospitals, and subway stations. The project was also used to investigate the potential of Dial-a-Bus as a transit service for customers with mobility issues.

The stated objective was to get cars off the road during peak rush hours, and the project did make a minor dent in traffic. However, demand was rather low, while costs were very high. The demonstration project ended in early 1975.

In 1973, the Social Services and Housing Committee of Metro Toronto requested that the TTC, along with other agencies, investigate the feasibility of providing specialized transportation services for people who were unable to use conventional public transportation. As a result of their work, a two-year pilot project named Wheel-Trans, Phase I, started operating on February 3, 1975 with 46 customers.

[ca. 1977]

Fonds 16, Series 836, Subseries 4, File 8, Item 2.

After nearly 50 years of service, Wheel-Trans now provides 4.2 million trips a year to over 42,000 customers.

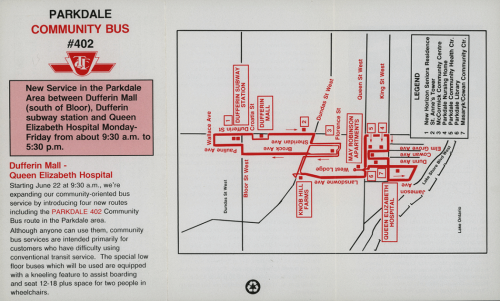

Late in 1990, the TTC initiated the Community Bus, another new service to make public transit more accessible for a greater number of people. The general objective of the community bus service was to meet travel needs not addressed by the existing grid configuration of routes, to provide coverage to such neighbourhood hubs as civic buildings, medical facilities, community centres, plazas, and arenas, and to provide an alternative to having to book a Wheel-Trans ride in advance. Target areas were those with large numbers of seniors, non-working adults, children, and single-parent households.

The first community bus route travelled along a six-mile route throughout the Lawrence and Bathurst area linking together several seniors’ homes, the Baycrest Centre, the Lawrence Square Shopping Centre, and the Lawrence West subway station. The Lawrence Manor route was such a success that four new community bus routes were launched in 1992. The new wheelchair-accessible routes, in South Don Mills, Parkdale, East York, and North Bathurst proved to be popular with a dedicated group of customers.

While there was a continuing increase in community bus passenger numbers into the early 2000s, by the 2010s, the numbers had declined as more of the TTC’s conventional bus, streetcar, and subway trains and stations became more accessible. Several community bus routes remain in place, still serving their neighbourhoods after almost thirty years.

Since the 1990s, the TTC has taken a leadership role in transforming its fleet and infrastructure to be accessible for people of all abilities. Citizen advocacy in this transformation has been and continues to be pivotal. The TTC instituted the Advisory Committee on Accessible Transit (ACAT) in 1992. This committee provides a mechanism for ongoing public participation in decisions affecting accessible transportation in Toronto. The Committee is comprised of volunteer members, who either are or represent the needs and concerns of seniors and persons with disabilities. ACAT meets monthly and reports directly to the TTC Board.

In recent years, concern for accessibility has influenced every aspect of the TTC’s operations. The first accessible subway station, Downsview (now renamed Sheppard West) opened in 1996. Two-thirds of the system’s subway stations are now accessible, with a target date of 2025 for all stations to have elevators, wide fare-gates, and power-operated doors. The first accessible full-sized buses entered service in 1996, and in 2011, the entire bus network became accessible. In 2014 the first streetcars that accommodated wheelchairs and scooters were introduced, and with the retirement of the last of the older streetcars in 2019, the entire streetcar fleet is now accessible. The TTC has also improved wayfinding and signage and used design and technology to make life easier for all. Included among the planned innovations are interactive touch screens that provide trip-planning and local area information in multiple languages, and beacon technology that allows customers, including those with vision loss, to navigate through stations using their smart devices. Accessibility benefits everyone.