This guide focuses on the history of the Chinese community in Toronto, and is illustrated with selections from the Archives’ collection of photographs, documents and drawings.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through Library and Archives Canada in the production of this guide.

This research guide is available in Chinese.

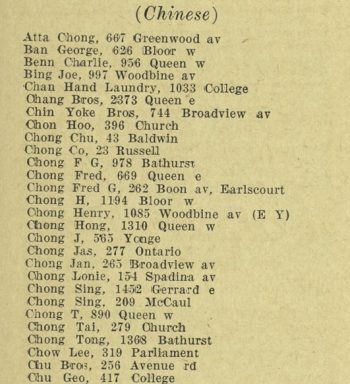

1878 – A Toronto city directory shows Mr. Sam Ching among the first Chinese working in Toronto. He ran a laundry downtown, at 9 Adelaide Street East. Over the next several decades, the directories show Chinese-run laundries spreading through the city.

1882 – A weekly bulletin from the Toronto YMCA mentions that nine of 16 Chinese living in Toronto were attending Bible classes on Queen Street West. A 1910 report from Cooke’s Presbyterian Church noted that its classes after Sunday evening service attracted over 100 Chinese students. Students learned the alphabet and simple words, as well as hymns and scripture lessons.

1902 – The Laundry Association asked Toronto City Council to levy a license fee on all laundries. It wanted to stop Chinese newcomers from starting more laundries. By then, about 100 Chinese-run laundries were operating in Toronto.

The City’s Property Committee approved a license fee of $50. The Chinese opposed the amount and wanted a lower fee reflecting the number of workers at a workplace. In the end, a fee of between $5 and $20 was adopted. The amendment was made by Alderman William Peyton Hubbard, Toronto’s first African-Canadian politician.

1905 – The Toronto Star newspaper notes some Chinese were starting a local branch of the Chinese Empire Reform Association. It sought to reform China’s monarchy. Chinese Freemasons, who had emerged a few years earlier in Toronto, supported another way to modernize China. They backed Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s revolution by borrowing funds against their building on York Street.

1909 – The City Directory shows a cluster of Chinese shops located at Queen Street East, at George Street. Another cluster was at Queen Street West at York Street. Chinatown emerged on Elizabeth Street, north of Queen Street. Earlier, a large Jewish community had lived in the Elizabeth Street area.

1910 – The Toronto Chinese Christian Association started a reading room and held English and Bible classes. In 1919, it became the Young Men’s Christian Institute, which conducted prayer and fellowship meetings, as well as open-air services. It also worked with students from China. In 1928, members helped start the Chinese Church of Christ, which became a Presbyterian congregation in 1956.

1911 – City assessment rolls show Mr. Gip Kan Mark was the first Chinese to own property on Elizabeth Street. On the first floor of 16 Elizabeth Street, a three-storey building, was a wholesale grocer, Ying Chong Tai. Its neighbours included a blacksmith, dairy, veterinary surgeons and horse stables.

Census returns show that from 1911 to 1941, Toronto had the third most populous Chinese community in Canada, after Vancouver and Victoria. To oppose the 1923 Canadian law that blocked Chinese immigration, a national organization emerged in this city because Toronto was closer to Ottawa.

1912 – In January, fifteen hundred Chinese gathered at Victoria Hall to celebrate the founding of the Republic of China, and the end of Chinese dynastic rule. A parade through downtown Toronto also marked the occasion. Toronto Mayor George Geary attended the celebration banquet held at the Chinese Freemasons’ hall.

1918 – Council Proceedings show City Council asking the Police Commissioners to grant business licences only to applicants who were British-born or naturalized British subjects. The Consul General from China appeared before the Police Commissioners to protest. The Chief Constable reported to Council that denying licenses was not possible, because subjects of allied nations, including China, held treaty privileges.

1919 – A mob of 400 men and boys stampeded through the Elizabeth Street Chinatown in November, smashing glass windows and looting Chinese stores. Mayor Thomas Church told the rioters, “I must have order in the city.”

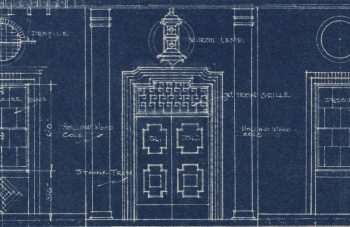

1922 – Assessment Rolls show a change of ownership at 24 Elizabeth Street, when the property was bought by the Lung Kong Brotherhood. The group tore down the existing structure and erected a three-story building. People surnamed Liu, Kwan, Cheung and Chiu had formed this group in Toronto in 1911 to provide mutual help for one another and to the support community.

1925 – A newspaper story told of a thousand Chinese marching along Queen, University and Dundas Streets to attend a service at Victoria Hall to mark the death of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, Father of the Chinese Republic.

1928 – City officials ordered Chinese café owners to fire their white waitresses. In 1914, Ontario had passed a law making it illegal for Chinese employers to hire white women. Ontario’s Chinese raised $2000 to fight the law. The Consul General from China intervened, and the law was not enforced until 1928. The law addressed unfounded fears that Chinese employers would take advantage of white women. Restaurants in Chinatown tended to serve Chinese cuisine, while Chinese-run cafes in other parts of Toronto usually served western food.

1933 – The Chinese United Dramatic Society was formed. Its predecessor was World Mirror, the first Chinese music group in Toronto, established about 1919. Toronto’s several Cantonese opera groups entertained the community, and also provided low cost board and lodging for the jobless and destitute. The Chinese United Dramatic Society invited music performers to come from Hong Kong and Guangzhou and train local amateurs. It purchased land at 96-98 Elizabeth Street and built a large hall with a capacity of 250 seats.

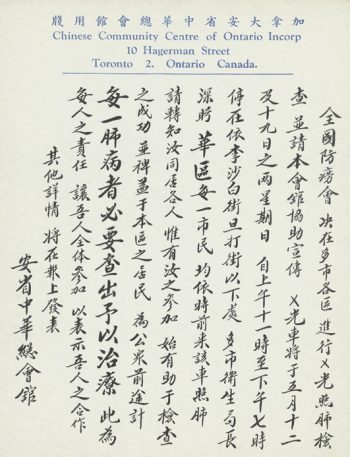

1937 – When the Sino-Japanese War started, the Chinese Patriotic League of Ontario was formed, with headquarters in Toronto. The Lung Kong Brotherhood provided office space for the League, and covered its operating expenses. The League raised funds for China’s war effort. In 1938, it looked into sending Dr. Norman Bethune to China. In 1941, one project of Ontario’s 7,000 Chinese was a $100,000 Spitfire airplane fund.

1941 – Two days after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, China declared war on Germany and Italy. China and Chinese Canadians became part of the Allied War Effort. Chinese and whites in Toronto combined efforts on the China War Relief Fund so that all Canadians could help China’s war effort. Toronto Mayor Fred Conboy was a patron of the fund, which raised $170,000 in 1942. World War Two marked a turning point in race relations in Canada. After the war, Chinese Canadians across the country received the right to vote.

1946 – In preparation for a proposed new civic square, to be located west of old City Hall, City Council passed By-law 16548 which restricted land use on the site to public purposes or parking lots.

These two views show changes on Elizabeth Street. The left view, taken in 1937, shows two stores at 60 and 62 Elizabeth Street (in the shorter building). In 1940, owner George Ying added a 2nd floor, and rented the space to the International Chop Suey House, shown in the photo at the right, taken in 1958. Both photos show the grocery store Sang Hong Sang at 64 Elizabeth Street (at the right of both photos), which was open from 1920 to 1957.

1947 – On January 1, Toronto voters approved spending for a new civic square and city hall. Council Proceedings from 1948 to 1958 show the City’s acquisition of sites in the Elizabeth Street Chinatown. The new civic centre was intended to spur downtown investment and development. This caused some businesses from the southern part of the Elizabeth Street Chinatown to move to the northern end of the street, closer to Dundas.

1951 – Toronto’s Chinese population was about 3,000. Ten years later, the number increased to 6,700 as a result of the wives and children of the early Chinese immigrants finally coming to Canada.

1955 – City officials preparing for new City Hall expropriated the shops and restaurants of Chinatown where 500 people had been employed. Construction started in 1962.

1964 – City voters elected Ying Hope to the Toronto Board of Education, where he served as chair in 1968. He was elected as Ward 5 alderman in 1969, and re-elected 1972-1982.

1967 – Toronto’s Commissioner of Development reported that it was not feasible to fix the remaining buildings of old Chinatown on Elizabeth St., and urged that the site be used for local government purposes. Chinese Canadians, who wanted to save the remaining Elizabeth Street Chinatown, formed the Save Chinatown Committee.

Canada’s immigration laws let more Chinese (mostly from Hong Kong) enter. A new Chinatown emerged around Spadina Avenue and Dundas Street.

1969 – Council Proceedings contain a report from the Save Chinatown Committee. After the report, City Council endorsed the idea of keeping old Chinatown.

A report in the Toronto Association of Neighbourhood Services records (fonds 1014) mentions how the Chinese Information and Interpreter Service started at the downtown University Settlement. The Service later became independent. The Settlement also held language and citizenship classes for Chinese immigrants.

1972 – The City of Toronto Archives holds a 1909 photograph of the Beverley Street Baptist Church, built in 1886. In 1972, Chinese Christians purchased the building (a designated Heritage Site) and it became the Toronto Chinese Baptist Church.

1975 – The fall of Saigon marked the end of the Vietnam War. Four years later, “Boat People” refugees from Vietnam, including many ethnic Chinese, began arriving in Canada. The largest numbers settled in Montreal and Toronto.

1984 – Scarborough Council Minutes show how elected officials responded to the distribution of hate literature aimed at Chinese immigrants. As the Chinese population rose in Scarborough, residents expressed concerns about traffic and parking around Chinese shopping malls.

1985 – Olivia Chow was elected to Toronto School Board. In 1991, voters sent her to Toronto City Council where she served until 2006. She was elected Member of Parliament for the Trinity Spadina riding in 2006.

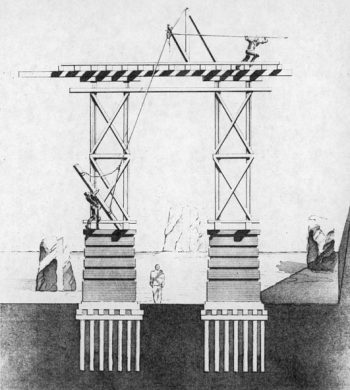

1989 – The Chinese community unveiled a memorial near Toronto’s downtown stadium to honour the Chinese workers who helped build the Canadian Pacific Railway.

1993 to 1997 – Hong Kong provided the most immigrants to Toronto (48,535 people, or 11 percent of newcomers). China provided the 3rd largest group (36,735 people). When the influx from Hong Kong declined after 1995, immigration from China rose. Newcomers from Hong Kong, Taiwan, China and Vietnam shared aspects of Chinese culture but came from different political systems.

1995 – A Markham town councillor complained that Chinese immigration and rapid commercial development were causing long-time residents to move away. The resulting protest from the Chinese community made news headlines across Canada and in Hong Kong.

1996 – A report by Statistics Canada staff shows the 335,200 Chinese living in Toronto (Census Metropolitan Area) formed the area’s largest visible minority group. They were 8% of the area’s total population. Toronto had Canada’s highest concentration of immigrants and visible minorities. Large numbers of Chinese lived in Scarborough, Richmond Hill and Markham.

Series 12, file 1953, item 23 and Series 12, file 1992, item 55R

Aerial views of Kennedy Road at Steeles Avenue, Markham (taken in 1953 and 1992), over the site of the Pacific Mall.

Pacific Mall opened in 1997 at the centre of the above view between Steeles, Kennedy and the railway tracks.

1998 – The Chinese Cultural Centre of Greater Toronto opened Phase One in Scarborough. It contained an art gallery, resource centre, reading room and classrooms.

2003 – Former Mayor Mel Lastman’s scrapbooks record how SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) had a serious impact on Toronto and its Chinese communities.

2006 – The 2006 census shows the 486,300 Chinese living in Toronto (Census Metropolitan Area) forming the area’s second largest visible minority group. They were 9.6 percent of the area’s total population.

2007 – In August, a Heritage Toronto plaque was unveiled at City Hall to commemorate the Elizabeth Street Chinatown. It is located at the north-west corner of Nathan Phillips Square, near the Archer statue.

The City of Toronto Archives research guide “Researching Your House” has been translated into Chinese.

Finding and using archival documents can differ from finding and using information from libraries.

For example, due to its great size, the Globe and Mail fonds* (Fonds 1266) is not fully described but many of its photographs are available. The Archives’ database contains many references to the Chinese in Toronto, but not every Globe and Mail item appears in it. Researchers should check the photographer’s logs (in the Research Hall) for further items. As well, some images are available as digital files or as microfilm, while others exist only in their original form.

*A fonds is a body of records that was created by a person or organization while carrying out its functions.

Immigration is a Federal responsibility. Library and Archives Canada’s Canadian Genealogy Centre has a guide to Chinese genealogy and family history.

Birth, marriage and death records are kept by the Provincial government. The Archives of Ontario website has several guides for doing family research.

Municipal assessment rolls and other records reflect immigrant activity around land and buildings. The Vancouver Public Library has a site for research into Chinese-Canadian genealogy

A good place to start is books and articles already written about Toronto’s Chinese. These can be found in the Archives’ Gencat database, using search terms such as “Chinese” or “Chinatown” in Monographs, under Level of Arrangement. Search also Papers and Theses in Forms Part Of field. Always check the bibliography and footnotes in published items for related materials, especially for articles that have not been catalogued as books.