Why was a subway needed? Quite simply, Yonge Street – Canada’s longest street, and Toronto’s busiest – was not wide enough to accommodate the traffic trying to use it. As a 1945 TTC document puts it,

The present congestion of traffic on Toronto streets threatens the very economic life of our City. Its welfare varies with the ease and efficiency with which people and goods can move throughout the city. The Commission does not propose to stand idly by and allow this deterioration of its services and of the city itself to take place. There must be a gradual separation of public and private vehicles, both of which are now trying to operate on the narrow streets originally designed for horse-drawn traffic.

“Statement of Policy,” Rapid Transit for Toronto, Toronto Transportation Commission, 1945, City of Toronto Archives, TTC reference materials, Box 3

A subway would remove commuters from those narrow streets, freeing up space for other traffic.

The Queen Street subway was never built. However, at the time, a second, lower station was built underneath Queen station, in case the Queen subway was built later. This unused station is one of two (the other is under Bay station) used by the TTC for training and commercial film shoots.

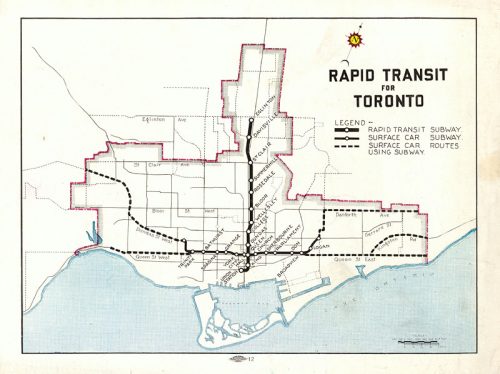

The proposed subway would run from Toronto’s railway hub, Union Station, through the office and shopping districts of downtown, to the edge of the developed city at Eglinton Avenue. Connecting buses along major east-west streets such as Eglinton and St. Clair avenues would serve the growing suburbs. Downtown, the subway was to be entirely underground, but once it entered the less densely populated (and cheaper) lands north of Bloor Street, it would come intermittently to the surface. There would be twelve stations in all, over a distance of 4.6 miles (7.4 km). The plans, designed by transportation consultants Norman D. Wilson and DeLeuw, Cather & Company, also included a subway running east-west on busy Queen Street, but this was never built.

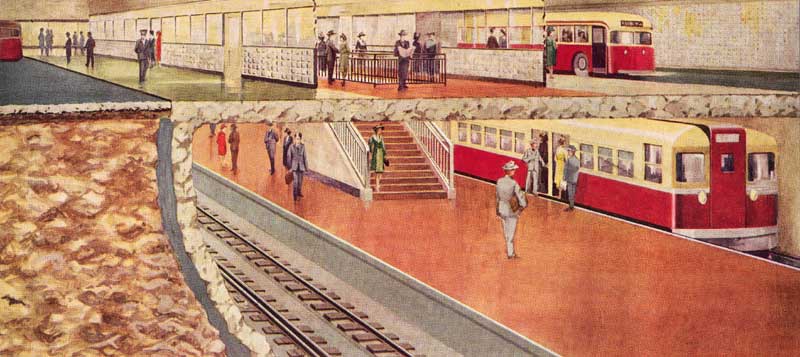

Passengers could transfer between the subway and buses while protected from the weather. Buses served Toronto’s growing suburbs west, east, and south of the older city core.

The depth of the stations was chosen so that passengers would not have to walk too far from street level to the subway train. As an added advantage, a shallow subway was cheaper to build than a deeper one.

Plans for a subway system had been put forward since 1910, but had always been considered too expensive. However, in the municipal election of January 1, 1946, voters approved the subway plan by a majority of almost ten to one. More detailed planning and the search for skilled workers to build the project took additional time, and construction began on September 8, 1949.

Back to introduction

Next page – Groundbreaking