Pile driving, earth moving, and concrete pouring were only the beginning. Track, lighting, signal equipment, and other working elements of the subway had to be installed. Cosmetic finishing was also required to provide the convenient, comfortable, modern commute the TTC promised its riders.

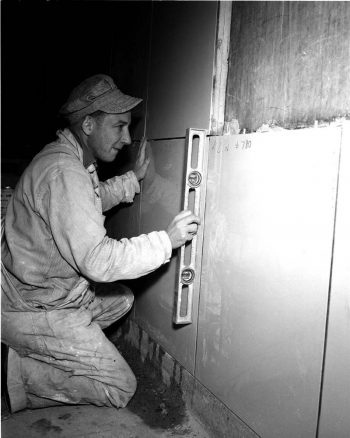

Tiles used in the stations were made of opaque glass bonded to a concrete backing. The large wall tiles, such as the ones shown here, were in light shades of yellow, green, and grey. On the platforms, narrow bands of darker tiles (black, red, green, or blue) were placed at the junction of wall and ceiling. Each station had a different tile/band colour combination, so that passengers could easily recognize stations.

The TTC used one of the earliest-built tunnels to test over 100 paints for their endurance of temperature and humidity extremes, abrasion, mildew, and general dirt. Ninety percent failed the sixteen-month test. The chosen paint was a chlorinated rubber-based paint that was tinted to match each station’s wall tiles.

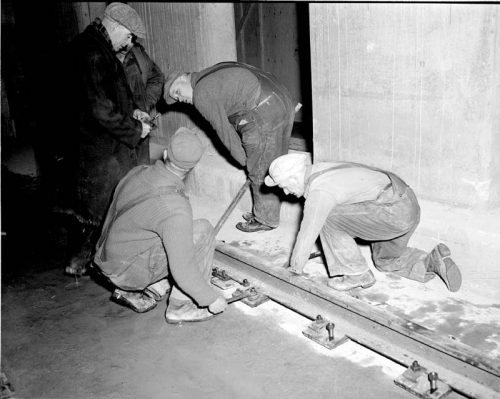

To reduce noise and vibration in the underground parts of the subway, heavy rubber pads were sandwiched between the steel rail plates (on which the rails rested) and the concrete floor to which they were bolted.

Subway cars were made by the Gloucester Railway Carriage & Wagon Company in London, England, which had also built many cars for the London tube. The TTC initially ordered 104 cars, of which 100 were steel. The last four cars, identical in appearance, were aluminium, so that the TTC could test whether the lighter aluminium cars cost less to run. (The TTC chose exclusively aluminium cars for the University subway line built in the 1960s.) The cars were 57 feet long; eight in total could fit the 500-foot station platforms.

The subway cars were designed with both comfort and efficiency in mind. The floors were made of cork and rubber to reduce noise, and the paint was of a special sound-deadening type. The windows could be opened at the top. Light levels were high enough to allow reading in the tunnels, and several lights per car were battery-operated in case of power failure. The 62 seats per car were covered in vinyl, and every one was located, said the TTC, “within five steps of the nearest doorway.”

All stations but one contained an underground mezzanine level, where passengers paid fares and obtained transfers before proceeding down another escalator to the subway level. The exception was Dundas, where due to soil conditions the track level had to be as close to the surface as possible. Therefore, Dundas station had no mezzanine level, and passengers paid fares on the same level where they boarded the subway trains.

Transfers had to be obtained from a dispenser (as this man shown is doing) and then inserted into a separate slot in the centre of the same machine to be stamped with the station name and time.

The subway cars were attached in pairs, with a driver’s cab (a very small control room) at each end. This arrangement meant trains could go in either direction without having to turn around first.

Back to introduction

Next page – Open for Business