Over the course of the 20th century, there were several proposals which would have significantly modified Toronto’s existing street system.

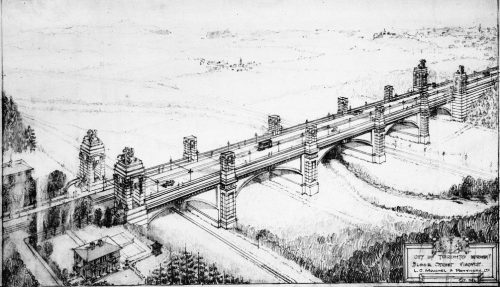

By the start of the 1900s, the growth in suburban development east of the Don River had made it clear that a bridge was needed over the Don Valley. Even so, the project was rejected by the electorate three separate times, in 1910, 1911 and 1912, until an alternate proposal by the Civic Improvement Committee addressed cost and aesthetic concerns.

When the work was tendered in 1913, bidders were free to submit their own designs, in steel or in concrete. They were also asked to provide two alternate designs, one that included the construction of a lower subway deck, and one that didn’t. The result was a fascinatingly diverse selection of unsuccessful proposals for what eventually would be realized as the Prince Edward Viaduct.

Ultimately, the span over the Don was built of steel on concrete piers, with a lower deck that was eventually used when the Bloor-Danforth line opened in 1966. For more information on the construction of the Bloor Street Viaduct, or more formally the Prince Edward Viaduct, please see our web exhibit, Bridging the Don.

By the late 1920s, with the increase in car ownership, downtown traffic congestion had increased significantly. The need for more thoroughfares through the city core became pressing. One improvement was to extend University Avenue – which then terminated at Queen Street – southwards.

In May 1928 the new Advisory City Planning Commission was appointed to recommend the best route for the extension. The Commission reported back the following spring recommending University Avenue be continued south to Richmond Street, then extended in a south-easterly direction, terminating at Front Street opposite the newly opened Union Station.

To mask the shift in alignment at Richmond Street, the Commission suggested the construction of a monumental traffic circle, Vimy Circle. In the centre, traffic would circulate around a vast memorial to Canada’s war dead. The commission also envisaged an axial road, running south-easterly from the circle to merge with Wellington at Spadina. However, the recent stock market crash of October 1929 had altered the appetite for such expensive works. The scheme was ultimately shelved with just the University Avenue extension being completed, and Vimy Circle being dismissed as a frill.

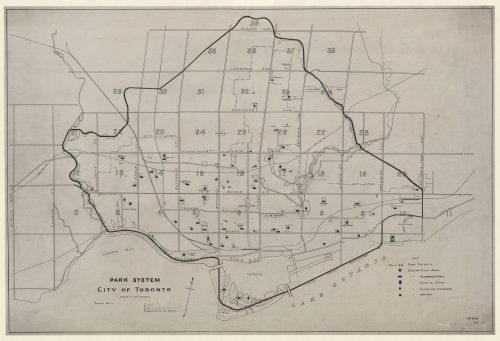

In 1912, gaining inspiration from the City Beautiful movement, the recently-established Toronto Harbour Commissioners released their master plan for the development of the Toronto waterfront. This plan called for a new boulevard along the waterfront. Partially completed as Lake Shore Boulevard, its extension through Toronto Island via bridges at the eastern and western gaps, was never realized.

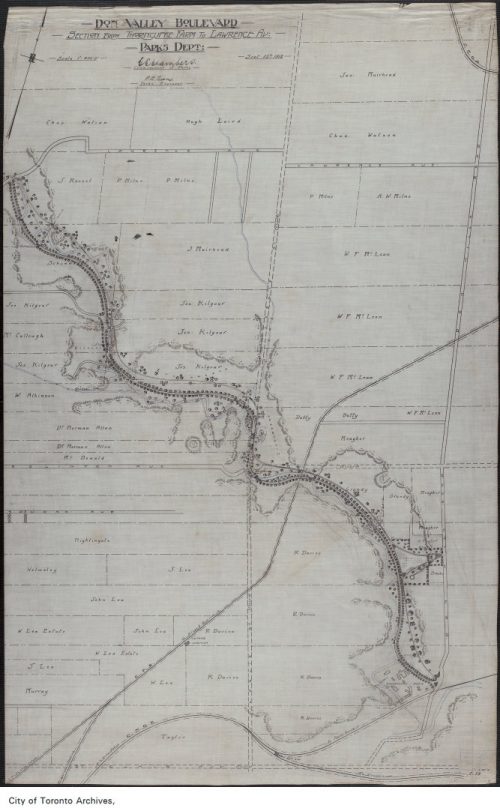

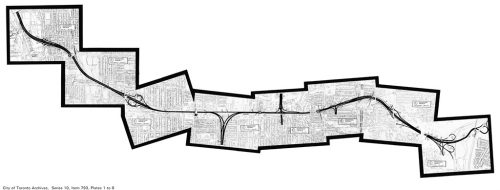

Drawing from the same inspiration, and the incessant lobbying of the Guild of Civic Art for Toronto, the City’s Parks Department developed plans for a ring road system around the city that would have incorporated the lakefront boulevard. A boulevard hugging the course of the Humber River and Black Creek in the west, would have linked to a similar boulevard in the east following the Don River.

The boulevard system was developed to deal with Toronto’s lack of continuous thoroughfares through the city. Although most of these designs were never constructed, they can be seen as clear precursors to the proposed developments after the Second World War.

Postwar road schemes focused less on creating beautiful civic spaces, and more on moving automobiles. The City’s 1943 master plan envisaged the construction of a network of either sunken or elevated “superhighways.” The idea was expanded in Toronto’s 1959 Official Plan, which featured an inner ring of expressways circling the downtown core, and an outer ring surrounding the new Metro Toronto.

The politics of pushing expressways through established residential neighbourhoods proved difficult. An early casualty was the Crosstown Expressway. Its route would have followed an east-west alignment parallel to Dupont Street, cutting through Rosedale. The Crosstown would have had links to the Spadina Expressway from the north, and the proposed Christie-Clinton Expressway, which would have run south to meet with the Gardiner.

In 1971, organized opposition saw the Province cancel the Spadina Expressway in mid-construction. The Spadina Expressway would have carved its way through the the Cedarvale and Nordheimer Ravines, razing large sections of the established neighbourhoods of Forest Hill and the Annex. This expressway was planned to link Highway 401 with the Crosstown Expressway. Only the stretch north of Eglinton Avenue, known as the Wiliam R. Allen Road, was constructed.

Three years later, the cancellation of the Scarborough Expressway spelled the end of the era of superhighway building in Toronto.

Back to Introduction

Next page – Public Transportation