Like Toronto’s dairy industry, the city’s meat processing trade began on farms and in small, local businesses. By the 1850s, however, the industry began to expand, largely fuelled by Britain’s demand for high quality pork.

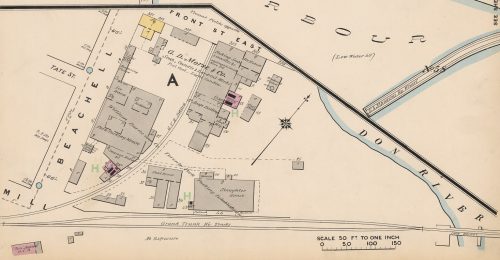

William Davies (1831-1921), the father of Toronto’s pork processing industry, believed in the superiority of Canadian pork and recognized the opportunity to develop a market for it in Britain. Davies made his first shipment of pork products to England in 1860 and by 1874 he had built the country’s first large-scale hog slaughtering facility on Front Street East near the Don River.

William Davies, who started his career in England selling groceries and pork products, also established a chain of meat and grocery stores in Toronto. Canada’s first retail grocery chain not only sold fresh meat processed in Davies’ plant, but also Davies-branded products such as cooked meats, plum pudding, pickles, and tea.

In a write-up about the business published in 1877, Davies was said to be installing equipment to produce blood and bone meal, which were used as fertilizer. The sale of animal by-products was vital to the profitability of meat packers. In addition to fertilizer, common by-products included tallow, lard, sausage casings, offal (organ meats), hides, and soap. Note the areas of the plant labelled Rendering Tallow and Soap Boiling.

Davies’ plant was the first in Canada to use a continuous rail system to move pigs from slaughtering to dressing and was the first to adopt artificial refrigeration He also advocated improvements in hog breeding to develop a better pork product. Even Toronto’s “Hogtown” moniker is said to be a reference to the number of pigs handled by Davies’ plant – over 500,000 in 1900 alone.

Following a series of scandals and financial setbacks that badly damaged the company’s reputation, William Davies Co. merged with the Harris Abattoir Co. to form Canada Packers in 1927, later becoming part of Maple Leaf Foods in 1991.

With the increasing domination of larger firms such as William Davies Co., there was widespread concern about the monopolization of the meat packing industry. The opening of the Municipal Abattoir on Wellington Street just east of Tecumseth Street in 1914 was, in part, a response to this issue.

Built and run by the City of Toronto, the Municipal Abattoir aimed to provide a centralized, sanitary, affordable slaughterhouse for independent, small-scale meat packers. However, the gradual decline of the independent packer combined with the facility’s high slaughtering costs made the Municipal Abattoir a financial liability. Two years after opening it was operating at only 19% of its total capacity.

In 1960, the plant was sold to Quality Meat Packers. One of the country’s last abattoirs located in a major urban centre, the plant closed its doors in April 2014, the victim of escalating pork prices. At the time of its closure Quality Meat Packers accounted for approximately 25% of Ontario’s total pork production.

In 1903 the Union Stock Yards opened for business on a site at the south-west corner of St. Clair Avenue West and Keele Street. Although distant from the heart of the city’s existing meat industry, the new location offered room to expand and good access to railway lines. The yards offered paved pens and alleys, a modern drainage system, and adjacent hotels, offices, banks, and streetcar routes – all necessary for the efficient operation of business. Incentives offered by the Union Stock Yard Company in the form of low-cost land deals were an additional benefit.

While the Stock Yards were initially envisioned as a site to buy and sell livestock, they quickly attracted meat packers such as Levack (1905), Gunns (1907), Swift Canadian (1911), and Harris Abattoir (1913), who were able to purchase their livestock from dealers operating in close proximity to their slaughtering operations. Other packing companies would later follow, including Hunnisett Ltd.(1932), Canadian Dressed Meats (1940), Prime Packers (1954), Grace Meat Packers (1960), and St. Helen’s Meat Packers (1980). The majority of these businesses set up shop on the north side of St. Clair Avenue West.

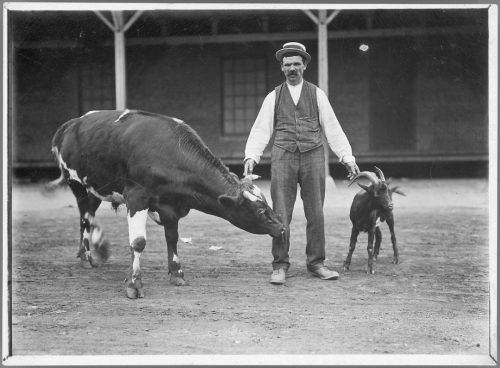

When livestock arrived at the Union Stock Yards, they were herded into pens on the south side of St. Clair Avenue West before being moved to the abattoirs on the north side. Lead animals were used to guide livestock into forcing pens, while avoiding the slaughterhouse themselves.

As the animals had to cross St Clair Avenue to get to the abattoir, livestock drives across the street were large and frequent. In one two-week period in October 1946, Swift Canadian conducted an average of 15 drives per day with 700 head of livestock per drive. Unsurprisingly, traffic blockages were a frequent problem. The abattoirs proposed building a tunnel under St. Clair but this was never realized.

In 1944, the Government of Ontario took over the Union Stock Yards from an American corporation that had acquired ownership in the mid-1930s. The newly renamed Ontario Stock Yards continued as a major source of employment and economic activity in the city after the Second World War. However changes within the industry, including the decline of rail shipments of livestock, the trend toward direct sales of animals for slaughter, and the migration of meat packing operations out of major metropolitan areas, all signalled that the age of the Stock Yards was coming to an end.

After more than 90 years of business, the Ontario Stock Yards closed its doors in 1994. Subsequent redevelopment of the site has combined big box retail with residential development, although a few meat packers still remain in the neighbourhood.