In its earliest days Toronto relied on small local producers for its daily supply of milk. As the city’s population grew milk had to be brought in from farms outside the city. By 1909 Toronto received nearly 20,000 gallons of milk each day from approximately 900 farms within a 40-mile radius, sometimes travelling for up to 36 hours before reaching the consumer.

The city’s milk supply chain was vulnerable to contamination from multiple sources: cows infected with bovine tuberculosis, typhoid, and diphtheria; unsanitary stables and milk houses; and dairymen and their families suffering from contagious disease. Unscrupulous producers were also known to adulterate milk with chemicals, chalks, and dyes to disguise changes in taste and colour caused by storage at improper temperatures.

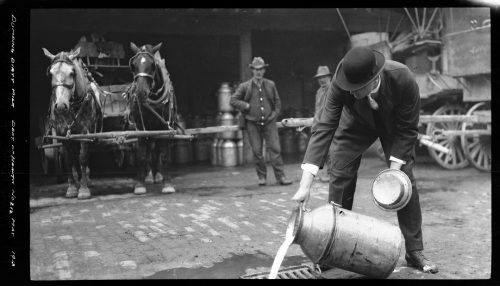

Milk arriving in Toronto was tested by City milk inspectors to ensure it was clean, free from chemicals or other contaminants, stored at the correct temperature, and contained the required amount of milk fat. Contaminated milk was destroyed by emptying it into the sewer. Sometimes it would be dyed red and returned to the farmer, in a can marked with a red “condemned” sign.

To improve the safety of the city’s milk supply, Council passed By-law 5791 (1911) which regulated the production, handling, and distribution of milk. Three years later, Toronto’s Medical Officer of Health issued an ordinance making pasteurization compulsory for all milk sold within the city. Pasteurization involves heating raw milk to a high temperature, then cooling it quickly before bottling. This improves the storage life of milk and kills disease-causing microorganisms such as those that cause tuberculosis, typhoid, and salmonella.

To assist in the monitoring of dairies and dairy farms, the Dept. of Public Health created a report card to grade the condition of cows, stables, and milk houses. Businesses scoring over 80% were published in the department’s Health Bulletin. The first report, published in late 1912, listed only 10 dairies. Three months later the number had climbed to 15 and included two prominent producers, Caulfield’s and City Dairy.

Caulfield’s Dairy started in 1888 as a one-wagon operation founded by Samuel Caulfield, an immigrant from Belfast. Originally located in Parkdale, the dairy eventually moved to premises on Roncesvalles Ave. By the 1920s, business was booming.

Caulfield’s had grown to include at least seven distribution branches, over 100 delivery routes, a chain of retail dairy bars, and a modern new facility at 45 Howard Park Ave. (1927). Caulfield’s success didn’t go unnoticed. In 1929, Caulfield’s, just like City Dairy, was bought out by the Borden Company, an American business looking to expand into the Canadian market.

Caulfield’s most notorious employee was Edwin Alonzo Boyd, bank robber and leader of the Boyd Gang. In 1939, Boyd’s father secured him a position at Caulfield’s loading and unloading crates of milk bottles for $18 a week. Things went sour when Boyd was transferred to a new role cleaning milk vats on the night shift. According to Boyd, “The vats would be scummy from the milk and they had to be cleaned with lye and boiling water and sprayed with a hose. The lye was pretty potent stuff. I didn’t know if it was dangerous for me or not.”* Unhappy with the work, he quit after only one month.*From Edwin Alonzo Boyd: The Story of the Notorious Boyd Gang by Brian Vallee.

City Dairy was the brainchild of Toronto businessman and philanthropist Walter E.H. Massey who wanted to create a safe and sanitary milk supply for Toronto’s citizens. Massey’s first experience in the dairy business was with Dentonia Dairy (est. 1896-1897), a 250-acre experimental farm and dairy operation located at Danforth and Pharmacy avenues on the site of the family’s summer home. The farm, which was originally intended to supply Massey’s family with milk, was noted for its progressive dairy facilities including a testing lab and steam-powered sterilization equipment.

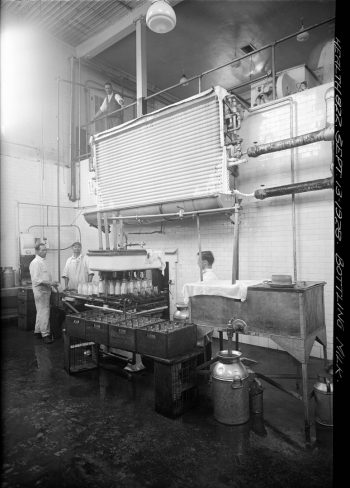

Realizing the demand for pure milk on a city-wide scale, Massey applied his experiences with Dentonia to a new enterprise, City Dairy. Located at 485 Spadina Crescent, the dairy was designed by Toronto architect George Martel Miller (who also designed the Gladstone Hotel) and was equipped with all the latest machinery, including the world’s largest commercial clarifier for filtering milk. City Dairy made its first milk delivery on January 30, 1901.

In addition to creating a state-of-the-art facility, City Dairy conducted 75,000 tests annually at its in-house laboratory to ensure its milk was free from contagions. It also hired a team of milk inspectors, ten years before the City, to examine conditions on suppliers’ farms. These practices, combined with the early adoption of pasteurization in 1903, gave City Dairy a valuable advantage in Toronto’s highly competitive dairy market. By 1915, City Dairy controlled 40% of the milk business in Toronto. Unfortunately, Walter Massey did not live to see it. He died in September 1901 from typhoid contracted during a business trip to Ottawa.

In 1930 City Dairy was bought out by the Borden Company. The Spadina Crescent complex served as the headquarters of Borden’s ice cream and fluid milk operations until 1962, when the land was required for development by the University of Toronto. Today the buildings serve as administrative offices for various U of T programs and services.