In 1837, William Gooderham (1790-1881) established Toronto’s first permanent distillery at the mouth of the Don River, using surplus grain from the milling business he had started with business partner James Worts (ca. 1792-1834). The combination of milling and distilling was not unusual in Upper Canada. As millers, Gooderham and Worts were already producing a waste by-product known as “middlings” that was being purchased by local distillers and transformed into whisky, the alcoholic beverage of choice during this period.

Unlike beer, whisky was more shelf-stable, had a higher alcohol content, and was made with readily available ingredients. It was also cheaper to buy than imported liquor which was heavily taxed. Gooderham’s first batch of whisky was completed in 1837; nearly a third of it was purchased by Joseph Lee, a storekeeper on King Street East near Frederick Street.

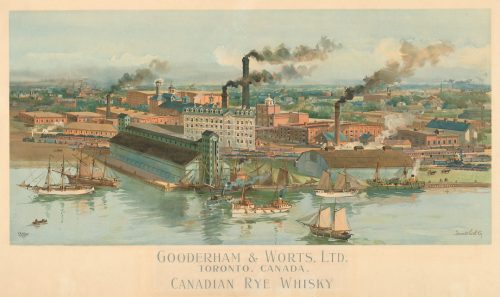

Between 1859 and 1861, Gooderham & Worts built one of the most modern distilleries in Canada, capable of producing over two million gallons of whisky per year. By 1877 Gooderham & Worts was hailed as the largest distillery in the world, with extensive facilities that included a private wharf, grain elevators, and a cooperage for barrel making. Construction continued on the site until 1895 when the last building – the Fire Pump House – was completed.

In 1916 the distillery complex was leased to the Imperial Munitions Board for use as a chemical manufacturing factory, a well-timed business move that coincided with the beginning of prohibition in Ontario. Under the leadership of Col. Albert E. Gooderham, the plant made approximately 1,000 tons of acetone annually, a component of gunpowder.

After the end of the war, the distilling operation remained dormant until businessman and bootlegger Harry Hatch bought it in 1923. Four years later, he merged Gooderham & Worts with his most recent acquisition – Hiram Walker Ltd. The newly created company continued to bottle liquor under the G&W brand; however, by 1957 the company had ceased all whisky production at that site. Instead, the plant shifted to rum and industrial alcohol – a line of business G&W had entered into in 1902.

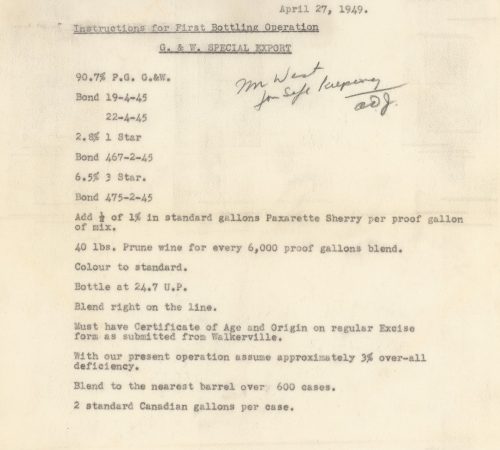

Likely created by the distillery’s Blender, this appears to be a recipe-in-progress rather than instructions for the production line.The notes describe a product containing a blend of 90.7% G&W whisky (Bond 19-4-45 and 22-4-45), 2.8% 1 Star (possibly a heavy-bodied rye, Bond 467-2-45), and 6.5% 3 Star (barley or rye malt, Bond 475-2-45).The bond numbers refer to a method of tracking the production date of spirits stored in the distillery’s warehouse. For example, “19-4-45” refers to a specific batch of barrels numbered 19, plus the month (4=April) and year (45=1945) in which those barrels were placed in the warehouse.Because the recipe is dated April 27, 1949, the Blender was working with four-year old whisky.

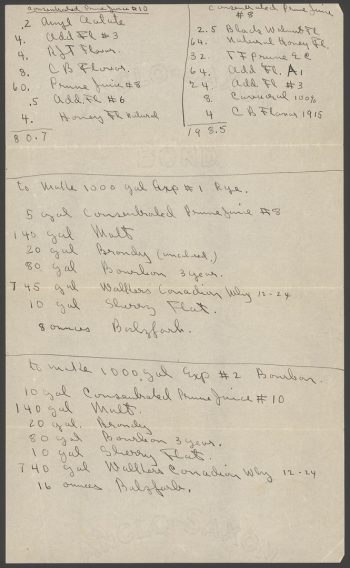

This document contains formulas for four products: #8 and #10 prune juice, Export #1 Rye, and Export #2 Bourbon.Prune juice was commonly used as a blender; the fact that Gooderham & Worts had two types on hand was a mark of quality. Similarly, sherry, brandy, and bourbon were considered to be top-end blenders, although they’re used less frequently today.Balzfarben, the last item on the page, is an additive used to standardize colour.

In 1987, Hiram Walker-Gooderham & Worts Ltd. was sold to Allied Vintners. The plant continued to produce liquor until 1990 when it finally closed its doors for good. Cityscape Holdings purchased the property in 2001 and began developing the site as an arts and entertainment destination known as the Distillery District.

Recipes from Host's Handbook: A Guide to Good Cocktails

ca. 1955

City of Toronto Archives

Series 1668, File 10

When Robert Henderson opened the Town of York’s first brewery at the north-east corner of Duchess and Caroline streets (now Richmond and Sherbourne streets) in 1800, it marked the beginning of Toronto’s brewing industry.

In the city’s earliest days, Torontonians were accustomed to drinking ales, stouts, and porters brewed by small, local concerns such as inns and owner-operated breweries. These styles of beer would have been familiar to the city’s English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants. Lagers, which are believed to have been introduced in 1858 and were popular with the city’s German-born population, also grew in demand.

As the city grew, so too did its brewing industry, encouraged by the development of the railways and improvements in brewing technology. Gradually, production was centralized in more sizable establishments like Copland’s brewery, the Toronto Brewing and Malting Co., the Dominion Brewery, and O’Keefe’s which produced increasingly large volumes of beer that could be sold well beyond their local markets. These changes in the way beer was made and sold led to the slow decline of small-scale producers.

Established in the 1820s by a Mr. Copland, the brewery was eventually taken over by his son William Copland before being sold in 1882. Under its new ownership, the brewery complex was expanded and updated. Publications from the 1880s describe the five-acre site, which employed approximately 50 men, as being very modern in design with three large ice houses and extensive vaults and cellars. By 1886, Coplands was producing 25,000 barrels of fine ale, stout, and porter a year.

Despite its successes, Copland’s closed its doors by 1915; yet that wasn’t the end of the story. In 1927, the brewery was purchased by the William Simon Brewery of Buffalo, NY and reopened under its familiar Copland name. In 1946, this enterprise was bought out by Labatt’s. Labatt’s continued to operate Copland’s until 1970 when it eventually opened its own facility in Etobicoke and the buildings were demolished. Today, the site is occupied by Toronto Police Service’s 51 Division.

Like so many other breweries in the city, the Toronto Brewing & Malting Co. set up shop on the site of an earlier brewery, one operated by John Aldwell (or Aldred) from 1846-1874 and possibly known as the William Street Brewery. In 1874, the Toronto Brewing & Malting Co. purchased the brewery and began producing ales, porters, and half-and-half (a blend of ale and porter) with a workforce of over 70 men.

In 1917, the brewery was purchased by Cosgrave Brewery of Toronto Ltd., a family-run business operating on Niagara St. just south of Queen. In 1921, the plant was sold to the National syndicate, which was eventually acquired by E.P. Taylor in the 1930s and transformed into an O’Keefe’s plant. Today the site is occupied by residential buildings with retail at grade.

The Dominion Brewery, located on Queen Street East just west of Sumach Street, was opened in 1878 by Robert Davies (1849-1916). It brewed ales and porters using Canadian malts and English, Bavarian, Californian and Canadian hops.

In 1926, the Dominion Brewery became part of the newly formed Canadian Brewing Corporation Ltd. Soon after, it was acquired by E.P. Taylor’s Brewing Corporation of Ontario Ltd. (later known as Canadian Breweries Ltd.), which, by the end of 1930 had taken ownership of ten breweries producing 26% of all the beer being sold in Ontario. While the Dominion name survived, the brewery operation on Queen Street did not and the plant closed in 1936. After extensive renovations between 1987 and 1990, the site, now known as Dominion Square, functions as commercial office and retail space.

The history of O’Keefe dates back to 1861 when Eugene O’Keefe (1827-1913) and his business partner Patrick Cosgrave (later of Cosgrave’s Brewery) purchased the Victoria Brewery on Victoria Street just south of Gould Street. An early adopter of lager, O’Keefe’s also brewed the more standard ales and stouts, as well as a product called Liquid Extract of Malt, which was sold by druggists to treat stress and insomnia.

The company evolved through several changes in structure until 1891, when the O’Keefe Brewery Co. of Toronto was formed by Widmer Hawke and Eugene O’Keefe. After the deaths of O’Keefe and Widmer in 1913, a holding company assumed control of the business.

By 1933, that holding company sold O’Keefe’s to E.P. Taylor and his rapidly growing Brewing Corporation of Ontario empire. The brewery, which was renovated between 1939 and 1940, continued producing beer until its closure in the late 1960s and subsequent demolition. Today the old O’Keefe brewery site forms part of Toronto Metropolitan University’s campus.

Consolidation was the name of the game in the 20th century. Companies such as Molson’s, Labatt’s, and E.P. Taylor’s Canadian Breweries Ltd. bought up numerous small breweries and concentrated production. Eventually, they themselves were acquired by multinationals such as Belgian-based InterBrew or MolsonCoors. One of the effects of market consolidation was the homogenization of beer styles, ingredients, techniques, and flavours, which resulted in fewer choices for Toronto beer drinkers.

The arrival of the Upper Canada Brewing Co. in 1985 marked the rebirth of the small brewery in Toronto. Other pioneering microbreweries would soon follow, including the Amsterdam Brasserie and Brewpub (1986), C’est What (1988), the Granite Brewery (1991), Steam Whistle Brewing (1998), and Mill Street Brewery (2002). These new craft brewers sought to revitalize the making of beer by employing a variety of ingredients and methods to produce a diverse range of styles and tastes. Today, Toronto’s booming craft beer scene suggests that the city’s taste for beer is still going strong.