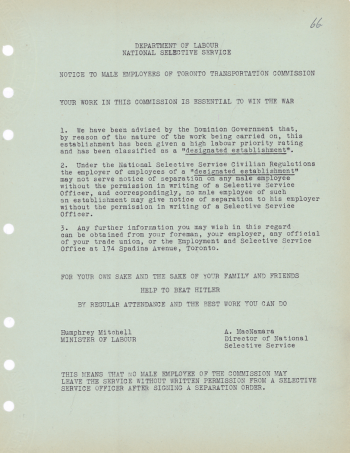

The Department of Labours’ National Selective Service was an agency in charge of the manpower mobilization. The TTC was declared an essential service. Employees were not required to go to war unless approved by the Selective Service. TTC employees who served were guaranteed a job upon their return home.

To accommodate this promise, the TTC redeployed those in its workforce to fill vacancies. However, by 1943 there was a significant shortage of employees within the TTC. Wives of employees serving overseas often were hired to fill these vacancies.

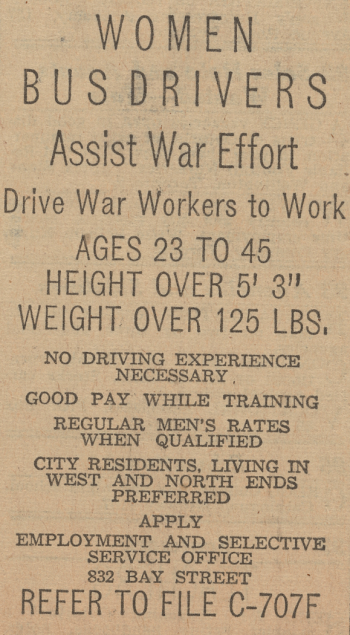

Women were first hired to fill traditional office roles as clerks and stenographers. Eventually, they were also employed to clean streetcars and buses. The TTC gave the matter much consideration before women were hired as bus drivers, operators, and conductors. Women began working as bus drivers on July 29, 1943, as conductors on September 3, 1943, and as operators on November 8, 1943. At the end of the war, the permanent male TTC staff returned, and these female staff left the TTC.

The TTC had been declared and essential service, as such, all TTC employees were exempt from military service. Special permission was required from the Selective Service agency to leave their TTC employ.

By 1943, the TTC decided to start to hire women to fill those vacancies created when men were granted permission to join the war effort. Advertisements were placed in newspapers and women were required to sign a three page contract stating that their employment was temporary; their employment would be terminated upon return of the male employees.

The TTC erected separate quarters at each division to accommodate the female operators. These buildings were slated for demolition upon the termination of the women employees’ contracts.

By 1946, the war had ended and the women who replaced the men were starting to be let go.

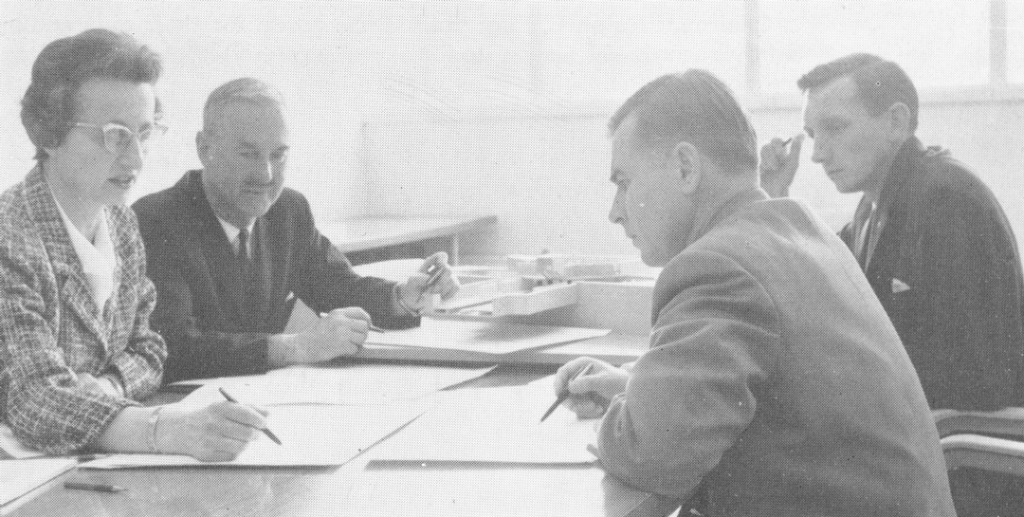

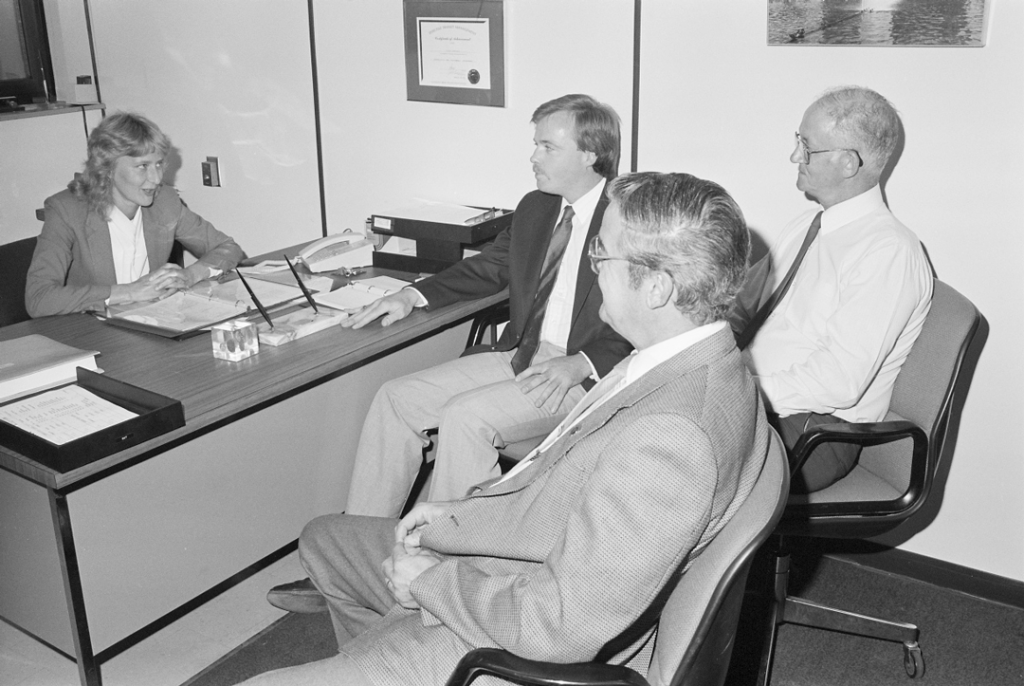

At the end of the Second World War, all female operators were let go, but this did not mean that the TTC did not hire women. As in the pre-war days, women were hired by the TTC to fill clerical and secretarial roles. Some held supervisory positions, and others filled roles in the architectural and engineering departments. Women were still involved in the operation of the TTC.

Herta Freyberg joined the TTC in 1948. She was an architectural draughtswomen, before being promoted to Senior Draughtswoman, Supervisory Draughtswoman, and Supervisor of Architectural Design. Herta helped design station layouts and architectural finish work on the Bloor Subway and Yonge Subway northern extension. Upon retirement, in 1979, she was the Superintendent of Architectural Design of the Subway Construction Branch.

Veronica Herczeg joined the TTC in 1953. She was involved in the design of the University Subway. In 1972, as Assistant Engineer (Design) of the Subway Construction Branch, Veronica was asked “Are women engineers different from their male counterparts?” Her response was “Why should they be?” Veronica’s other positions in the Engineering and Construction Branch (formerly Subway Construction Branch) included Senior Structural Design Engineer, Design Co-ordinator, and Project Manager. Veronica retired in 1988.

In 1973, with a continued shortage of operators, the TTC supplied a report in which it stated “It is illegal for the commission to discriminate in the hiring of operators and drivers on the basis of sex” (TTC meeting no. 1136, report no. 12). This report further looked at reasons why women might not want the job. Not only were height, weight, vision, and other qualifications sought, applicants would have to work shifts which might fall on weekends, nights, and holidays. This report did note that once women, who were successful candidates, were seen as drivers/operators, this may increase the number of future female applicants.

By 1980, the TTC committed to the Ministry of Labour that it would intensify its efforts to increase the number of women hired in non-traditional roles. The TTC created its first corporate policy on Equal Opportunity in 1983. This policy noted that hiring would be based only on qualification and that promotion would be based on merit. By 1989, this corporate policy was updated and expanded and it was continuously updated and modified to reflect changes in society and the TTC workforce.

In the 1980s, the role of affirmative action became a function of the TTC’s Personnel Department. In 1988, the Equal Opportunity Department was created. This department was responsible for advancing equal employment and equal opportunities, a function once held by the Personnel Department. In order to fulfill its mandate the department would be involved in outreach, as well as create strategies, liaise, and establish programs to develop a work environment that would showcase full representation and participation of all groups. While this department was dissolved in 1995, the work it had accomplished was adopted into the TTC workplace culture and in time the formalized functions that had belonged to the Equal Opportunity Department became part of the Human Rights Unit and the Human Resources Department.

Irma James was the first Black female streetcar operator hired by the TTC. Taking classes at Humber College in 1976, Irma knew she wanted to drive for the TTC. After applying in 1982, she was hired and worked for the TTC as an operator from 1983 to 2007. Irma was based out of Russell Division and drove the Canadian Light Rail Vehicle and Articulated Light Rail Vehicle. She loved her job saying “It was the best thing I ever did”.

Edelgard von Zittwitz joined the TTC in 1975 and was one of the first female operators since WWII. She worked out of Eglinton Division and Wilson Division before becoming the Supervisor of Administration at the Operations Training Centre. From there, she moved on to become Superintendent at Davenport Division before being promoted to Assistant Manager, District I and then Manager of Transit Administration. In 1987, Edelgard and TTC Operator Dee Carty were highlighted in the publication “Making Choices! – Women in Non-Traditional Jobs”.

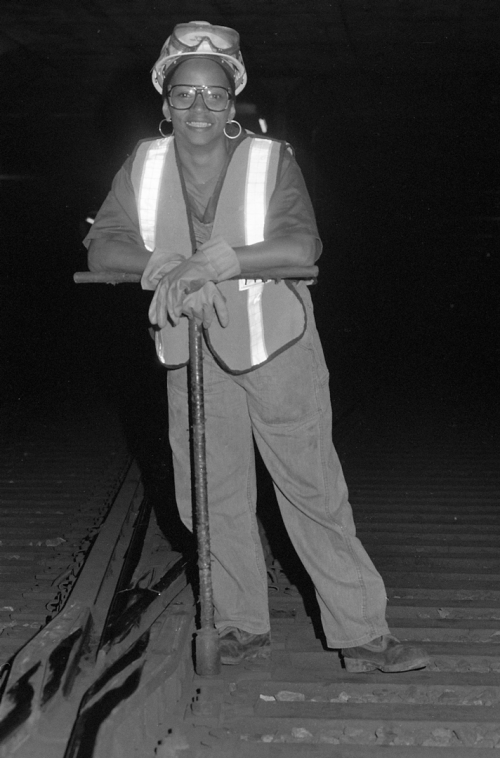

Lyn Morgan was hired by the TTC in 1988. She applied upon attending a women’s employment seminar co-sponsored by the TTC and Employment Canada. At the seminar, the Commission stressed that it was looking for women to join what were deemed “non-traditional roles” at the time. Lyn applied for the position of Track Labourer, and became the first Black woman, and the first woman period, to be promoted to Temporary Leadhand.

The TTC created a Diversity Plan in 2008. Under this plan the TTC actively sought to make sure its policies promoted diversity and that diversity would become a priority at all levels of the organization. Annual updates were produced which captured these successes. In 2015, the TTC created the Diversity and Human Rights Department to centralize diversity and inclusion initiatives and advance these initiatives through TTC policies and programs. Under this department the TTC launched its first Diversity and Inclusion Plan in 2015. In 2020, the Diversity and Culture Group was formed. Its goal is to bring together a variety of functions held by different departments within the TTC as a means to ensure the diversity and inclusion become core functions of TTC operations. In 2020, the TTC also released a 10-point action plan on diversity and inclusion. Under this plan the TTC will continue to actively create a workforce which is inclusive and as diverse as the public it serves.