Toronto has had an African Canadian population from its early days as a settlement. Its inhabitants included enslaved women, men, and children, Black Loyalists, and African Americans escaping enslavement in the United States. It also included rural Black Canadians moving from Nova Scotia or south-western Ontario, as well as people from the Caribbean and the African continent. Members of each of these groups have contributed to the growth of Toronto as a unique city.

Finding documentary evidence of the African Canadian population in the City Archives can be a challenge, particularly from the early years. Here are a few samples.

The following petition to the Mayor of Toronto was written and signed by members of the city’s Black community in 1841. They were requesting that a performance by an American company of actors portraying black people in an insulting manner be prevented from being shown in the City.

This is one of several such petitions presented to City Council in the 1840s. In 1840, Council passed a by-law that enabled it to license travelling theatrical groups and circuses. In July 1843, Council refused to let a circus perform unless performers promised not to “sing songs or perform acts that would be insulting to ‘the gentlemen of colour’ of the city.” The Blacks in Canada: A History, Robin Winks (1971, p. 150).

Petition from people of colour residing in the City of Toronto to His Worship the Mayor of Toronto

October 14, 1841

City of Toronto Archives

Series 1081, Item 785

To

His Worship the Mayor of Toronto

The petition of the undersigned, People of Colour; residing in the City of Toronto: Humbly Sheweth;

That your Petitioners are informed that a Company of “Circus Actors” from the United States (now travelling in this Province) are shortly to visit this City for the purpose of performing &c.

That Your Petitioners from the general and almost invariable practice of such Actors in their performances, have good reason to apprehend annoyances and insults, in the manner they endeavour to make the Coloured man appear ridiculous and contemptible in the eyes of their audience. Your Petitioners would humbly pray that Your Worship would be pleased to prevent the occurrence of such annoyances and insults, as Your Petitioners believe that such attempted Exhibitions of the African Character are not at all relished or approved of by the sensible and well thinking Inhabitants of this Community.

And Your Petitioners as in duty bound, will ever pray.

Toronto, 14th October 1841.

(James Johnson and 28 additional signatures attached)

Toronto City Directories were published almost annually from the 1830s to the early 21st century. They allow us to locate where someone lived and who or what was at a particular address. The 1846 and 1850 City Directories also identified some Torontonians as coloured. However not all Black Canadians were identified as coloured.

These directories are a valuable source of information about the city’s Black population at the time.

Churches played a crucial role within Black communities in the early 19th and 20th centuries and were often the first institutions established. They not only served as places of worship, but provided the community with a social, economic and educational hub.

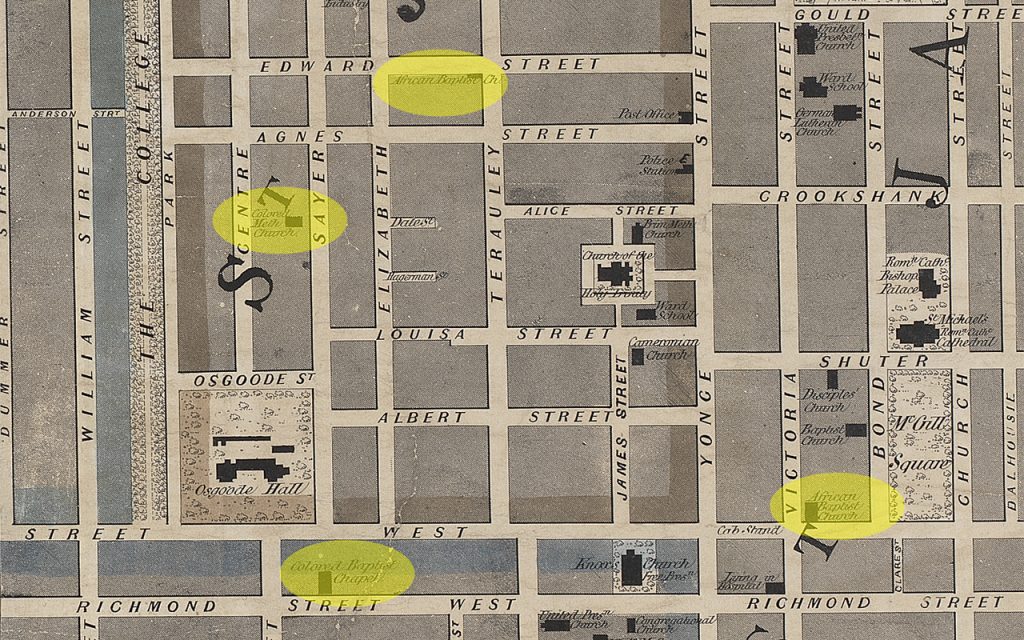

This detail from the 1857 Plan of Toronto illustrates the close proximity of four historic Black churches, all located in the St. John’s Ward district of the city. Many of the Ward’s residents during this time were refugees who had fled enslavement in the United States. These four churches, and the communities they represented, can trace their histories back to the earliest days of the city.

Possibly the oldest Black institution in Toronto, the First Baptist Church was established in 1826 by twelve people who were formerly enslaved. Led by Washington Christian, they began worshipping in people’s homes. By 1841 their congregation had grown to warrant a purpose built structure at the corner of Queen and Victoria streets, the present day site of St Michael’s Hospital. They then moved to a building on University Avenue in 1905, until finally, in 1955 they moved to their new and present day site on Huron and D’arcy Streets.

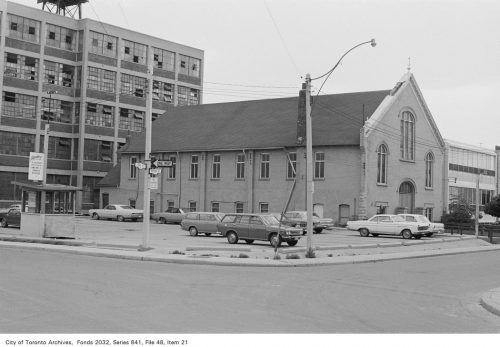

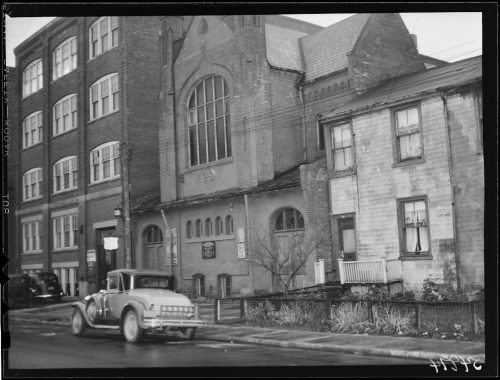

Established as early as 1833 by both freed men and those who had escaped slavery, the congregation of the Grant African Methodist Episcopal Church initially met in the homes of its members until finding a permanent site on Richmond Street West in the 1840s. In 1912 the church moved to a new location on the corner of University Avenue and Elm Street, where it remained until the larger property at 23 Soho Street, shown in this photograph, was acquired in 1929. The congregation moved again in 1991 to Gerrard Street East where it continues to worship today.

The British Methodist Episcopal Church established its first building in Toronto in 1845. It served as a social, political and spiritual centre for the Black community in Toronto and as a possible terminus of the Underground Railroad. Located at 94 Chestnut Street, it remained at this site for over one hundred years until 1955, when it merged with the Afro-Community Church on 460 Shaw Street. The congregation now meet at the corner of Eglinton Avenue and Dufferin Street.

This image was likely taken in the Agnes Street Methodist Church, which was on the south-east corner of Bay and Dundas (formerly Agnes) streets. The building was constructed in 1874 for the Bible Christian Church. When this group merged with the Methodist Church in 1884, the building became home to a predominantly African Canadian congregation. It was converted into a Jewish theatre in 1909.

It was extremely challenging for Black workers to find employment in Toronto in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many jobs were controlled by unions or trade associations that excluded blacks from joining. This forced them into the lowest paid, lowest status and often most dangerous jobs.This image depicts a group of labourers repairing Jarvis Street in the 1890s.

This photograph was taken at the dedication of a plaque in memory of the members of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, an all-Black non-combat battalion that served in the First World War. The plaque is in the main hall of Queen’s Park.

Rev. Mrs. H.F. Logan and Rev. H.F. Logan, who spearheaded the campaign for the plaque, are at left of centre. Included in the photograph are Premier Ernest Charles Drury, publisher J.R.B Whitney and Sir Henry Pellatt in the center. Rt. Rev. Samuel R. Drake, General Superintendent of the British Methodist Episcopal Conference, Ontario, is featured on the right with his cane.

African Canadians have played important roles in the defence of Canada. Today, they are honoured and celebrated for the victories they helped create at home and overseas. No. 2 Construction Battalion (the Black Battalion) is an important part of Canadian history.

During the First World War many African Canadian men who tried to serve Canada were told they were not welcomed. For two years African Canadians and their allies fought against anti-Black racist recruiting practices, but officials did little to end those practices. In 1916, officials fell on the idea of creating No. 2 Construction Battalion (No. 2 CB) as a way African Canadians could serve. Created on July 5, 1916, No. 2 CB was largest all-Black unit created in the history of Canada. After Daniel H. Sutherland took command, the Black Battalion began recruiting across Canada. Most of the non-commissioned personnel were Black, and except the Chaplain, Rev. William Andrew White, all the officers were white.

Regardless of their identities, construction battalions were vital to the war effort. Despite being under strength, No. 2 CB sailed to England in March 1917, where it reorganized as No. 2 Construction Company. In May, No. 2 Construction Company was sent to the Jura Mountain region of France to serve with Canadian Forestry Corps. No. 2 returned to Canada in 1919 and was disbanded in 1920. The Black Battalion leaves a legacy of service to country and persistence in fighting for equality: this legacy has finally received national recognition.

Credit: Black Canadian Veterans and AfriCanadian Searchers

This photograph, which appeared in The Globe and Mail of June 1, 1946, captures a Welcome Home Banquet held for veterans at the Afro Community Christ Church on Shaw Street. Left to right: Pastor of Christ Church, Rev. Dr. C.A. Stewart welcomes Sgt. F.N. Richards, RCAMC; Cpl. L. McCurtis, and SQMS H. T. Shepherd, MBE.

In the early 20th century, many young single women moved to the city to find work. Concerns were raised about the physical and moral safety of women living alone. Organizations such as the YWCA provided accommodation at reasonable cost. Ontario House was specifically for Black women. Like other YWCA buildings, it probably provided both dormitory-style and private bedrooms, and sitting rooms for daytime occupation.

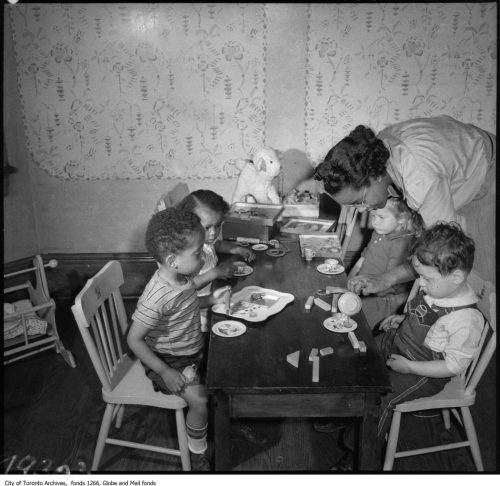

The Home Service Association engaged in social work and recreation, and provided educational programs and scholarships. Originally established to provide ‘home comforts’ such as socks and sweaters to Black servicemen during the First World War, the association later developed as a community and social centre which included a nursery. The University of Toronto’s Transitional Year Program can trace its roots to a program created by the Home Service Association.

Born near Bloor and Bathurst streets in Toronto, William Hubbard (1842-1935) was the city’s first Black elected politician. He was a member of council for 15 years serving as an Alderman and as a member of the Board of Control. The son of freed slaves from Virginia, Hubbard was educated at the Toronto Normal School, then apprenticed as a baker, a trade he was engaged in for over 20 years.

Hubbard was also Chairman of a special committee and spearheaded an effort to win provincial legislation to enable the City to generate, produce, lease and develop hydro-electric power, a move that established the Toronto Electric Hydro system. Hubbard was also active in two Black organizations-the Home Service Association and the Musical Literacy Society of Toronto.

The Archives holds Hubbard’s papers, which include letters he received, and newspaper clippings. These papers illuminate both the ceremonial and the everyday duties of a respected municipal politician of his day.

The above image depicts William Hubbard and Sir Henry Pellatt (1859-1939) signing the guest register at a Toronto Normal School reunion event. Both were former pupils of the school.

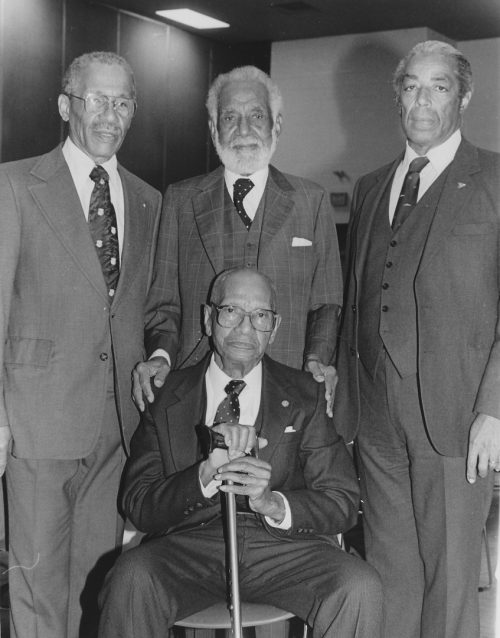

Donald Willard Moore (1891-1994), was a community leader and civil rights activist who fought to change Canada’s exclusionary immigration laws. In 1954 he led a delegation to Ottawa highlighting Canada’s discriminatory immigration laws, which denied equal immigration status to non-white British subjects. This led to the relaxation of immigration laws allowing West Indians to find employment in Canada. Moore was awarded the Order of Canada in 1990.

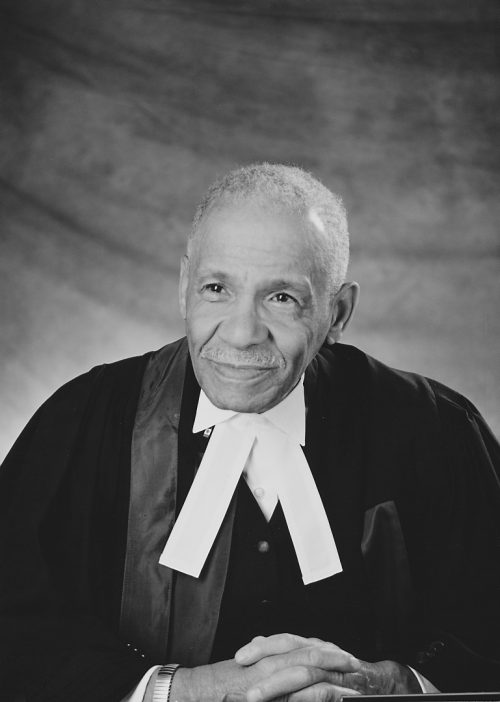

Stanley Grizzle (1918-2016), a human rights advocate, labour activist, and writer, was born in Toronto to Caribbean immigrants. He was part of Moore’s 1954 delegation to Ottawa, and served on the Ontario Labour Relations Board. He later became the first black Judge in the Court of Canadian Citizenship. Grizzle was awarded the Order of Canada in 1995.

Bromley Armstrong (1926-2018) was a union leader, community organizer and civil rights activist. A former Ontario Human Rights Commissioner, he was a central figure in campaigns that led to Canada’s first anti-discrimination laws. He received the Order of Canada in 1994.

Gairey (1898-1993) was a community leader and activist. He began campaigning for civil rights in 1945 when his son was refused entry to a skating rink because of the colour of his skin, leading to Toronto’s first anti-discrimination ordinance in 1947. With Donald Moore, he helped found the Negro Citizenship Association, advocating for changes to Canada’s discriminatory immigration law. He was awarded the Order of Canada in 1986.

This image includes all four of Toronto’s most prominent civil rights activists of the mid-20th century.

Born and raised in Toronto, with familial roots that date back to pre-Confederation, Rosemary Sadlier is the former president of the Ontario Black History Society (1993–2015). She is a social justice advocate for African Canadian achievement and advancements in the education system. She has been recognized as part of the driving force for Toronto to celebrate Black History Month and Emancipation Day since 1995. Some of her honours and awards include: the Order of Ontario, the William Peyton Hubbard Race Relations Award, Women for PACE Award, the Black Links Award, the Planet Africa Marcus Garvey Award and the Harry Jerome Award and the Lifetime Achiever Award from the International Women Achievers’ Awards.

Caribana, known as the Toronto Caribbean Carnival since 2011, has run annually since 1967. It was first performed as a gift from Canada’s Caribbean community as a tribute to Canada’s Centennial. The carnival is now the largest event of its kind in North America with over 1 million participants annually.

Influenced by the pre-Lenten Trinidad and Tobago Carnival, the festival is highlighted by a street parade traditionally held on the first weekend in August in commemoration of the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834. The carnival consists of costumed dancers and live Caribbean music. Work on the costumes takes a year to complete, beginning soon after the previous year’s celebration.

The Archives has a number of documents recording the history and organization of this event, including photographs, reports and correspondence.

At the Archives we work to preserve the history of Toronto. If you have documents such as photographs, letters, diaries, books, business records, or anything else that reflects life in Toronto in any era, and you would like to see them stored safely and made available to anyone interested in history, we would happy to talk with you about donating them to the Archives.

If you want to learn more about Black history in Ontario and Canada, take a look at these further resources.