Program for unveiling of Henry Moore’s The Archer

October 27, 1966

City of Toronto Archives

Series 374, File 403

Henry Moore’s The Archer (1964-5) arose out of Viljo Revell’s respect for and growing friendship with the English sculptor (then nearly at the height of his reputation). The idea that Moore might create something with this site in mind was necessarily an informal suggestion because the architect was in no position to commission a work in the months before he died. (Revell was to complain that ‘it was…strange that the architect was invited to be a member of the art committee,’ in a letter to Eric Arthur, its ubiquitous chairman, maintaining that in his experience ‘the architect acted as architect, in other words as preparer of the matters, presenting them and making proposals; and the committee would act as the client.’) In any case, the work proceeded, and purchase of a cast for $120,000 was recommended. But, worried about expensive frills, Council refused to authorize it. This touched off a controversy, ultimately resolved through a public subscription fund launched by Mayor Philip Givens. The Archer does more than grace Civic Square; from the day the sculpture took its place there (the unveiling was held on October 27, 1966), it appeared to focus the Square and the Hall, although far off the centre of either. Like its namesake, The Archer gives the appearance of a strong body responding, of equipoise and grace. It seems capable of action—and of evoking reaction—in any of several directions. Indeed, it seems not so much to respond to the curving planes of the building beyond and above it as to have called them into play—like trajectories charted and given substantial form.

Since its opening in 1965, Toronto City Hall has become much more than a place to conduct the business of a great city. As the symbolic heart of Toronto, it reflects the vitality of the community through the display of unique permanent pieces of public art that have been added to the complex over the years.

The examples shown here are but three of the many pieces of exceptional art that accent the architecture of City Hall.

The sculptural mural Metropolis, located along the east wall inside the main doors of City Hall, was the winning submission in an art competition held in 1974 to select a permanent work of art to complement Toronto City Hall’s unique architectural style.

Toronto artist David Partridge regards his sculpture as a symbolic interpretation of a great metropolis, but not of any city in particular.

Metropolis was created from more than 100,000 common nails. The mural is made up of nine panels each weighing at least 180 kilograms. The centre core is a circle of massed copper nails which indicate the heart of the city. In concentric circles, the central panel grows like treed ravines that enclose the city’s heart. The widened circles are bisected by grids that reflect the suburban regions and beyond.

Views to the City was the winning submission in a public art competition held by the City of Toronto in 1987.

Created by artists Brian Kipping and John McKinnon, the work is crafted in copper and glass mosaic tiles to present a roof-top panoramic view to the east and west of City Hall, depicting both present-day and nineteenth-century Toronto.

Kipping covered both facing walls with glass mosaic tiles. The west wall is a translation of a photograph taken by the artist from the roof of City Hall showing Lake Ontario, Sunnyside Pavilion and, in the distance, Port Credit. The Crane in the east side of the mural belongs to the period in the 1960s when the City Hall was under construction.

Sculptor and furniture designer John McKinnon created three- dimensional, life-size architectural details that refer to the rooftops of buildings that were in existence in nineteenth-century Toronto. The copper elements were executed by John Udrovskis Coppersmith & Co.

On the west wall, a pediment recalls part of the old City Hall, a spire from St. George the Martyr Church in Grange Park and a cornice that was borrowed from the past to make a comfortable bench. On the east wall there is a cupola and another cornice.

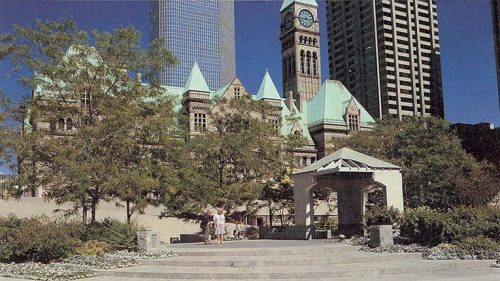

The Peace Garden, as it looked before 2016, located in Nathan Phillips Square, commemorates Toronto’s sesquicentennial in 1984 as a lasting physical expression of the desire for world peace shared by Torontonians.

The task of giving physical expression to this idea was given to the Planning and Development Department’s Urban Design Group.

The Peace Garden measures 600 square metres and consists of a small sculptured structure, an eternal flame, a pool and stone platforms and wall.

The central structure is a simple cube with a pitched roof, the edge of which has a damaged appearance to signify conflict and evoke images of buildings once present and now vanished. The north-west corner of the cube is broken away, reminding us of civilization’s frailty and war’s destruction. The eternal flame adjacent to this corner appears to support the structure, symbolizing the hope and regeneration of mankind.

To depict global unity, each of the shelter’s four doorways open to a cardinal point, and walkways join the Peace Garden to other elements on the square.

In September 1984, His Holiness Pope John Paul II lit the Eternal Flame of Peace using a torch ignited at the Hiroshima Peace Shrine, and poured water into the pool that was taken from the river that flows through Nagasaki. The Peace Garden was formally dedicated a month later by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

In 2016 the Peace garden was substantially modified and relocated to the north-west side of Nathan Phillips Square.

Back to introduction