This page contains links to background information related to the Baby Point Heritage Conservation District Study, including direction from City Council. relevant staff reports and reference documents that guide the study and evaluation of Heritage Conservation Districts in Toronto.

Review the Frequently Asked Questions document to learn more about Heritage Conservation Districts in general, and the Heritage Conservation District Study process.

On May 13, 2014, Etobicoke York Community Council adopted EY33.39, which nominated the Baby Point area for study as a potential Heritage Conservation District.

On March 31, April 1 and 2, 2015, City Council adopted PG2.8, which authorized and prioritized the Baby Point Heritage Conservation District for study.

Proceeding from Study to Plan Phase for the Proposed Baby Point Heritage Conservation District

On July 12th the Toronto Preservation Board received the Baby Point Heritage Conservation District Study, and endorsed the preparation of the baby Point Heritage Conservation District Plan, including any additional archaeological testing within City-owned lands as may be needed.

The Baby Point HCD Study is being completed in accordance with Heritage Conservation Districts in Toronto: Policies, Procedures and Terms of Reference as adopted by City Council.

Section 3.1.6 of the City of Toronto’s Official Plan includes policies that direct the City to identify, protect and conserve heritage conservation districts within the City.

The Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport created the Guide to District Designation under the Ontario Heritage Act to inform the identification, study and implementation of heritage conservation districts in Ontario.

Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act allows municipalities to designate heritage conservation districts.

The Baby Point HCD Study recommended that an HCD plan be developed for Baby Point, based on the identified cultural heritage value and heritage attributes of the neighbourhood and in accordance with the Ontario Heritage Act and the City of Toronto’s terms of reference for HCDs. It also identified a draft list of properties that contribute to the heritage value of Baby Point. You can learn more about the boundary, heritage attributes and contributing properties below, or by reviewing the HCD study report above.

The proposed Baby Point HCD boundary encompasses the Baby Point neighbourhood, an area that retains a high degree of integrity and is representative of the planned garden suburb envisioned and developed by Robert Home Smith.

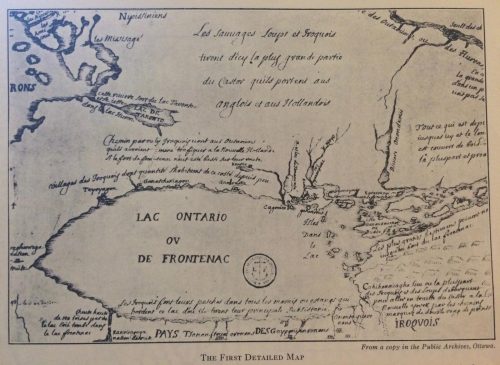

Baby Point was the site of indigenous use dating back thousands of years, including the Seneca village of Teiaiagon – one of the few known indigenous villages within present-day Toronto. The Toronto Carrying Place Trail, an important trade and transportation route between Lake Ontario and Lake Simcoe and a National Historic Event, is associated with this site.

Baby Point also has strong associations with Toronto’s French history – French explorers and missionaries are known to have visited Teiaiagon and used the Carrying Place Trail, an early French trading post may have been built on the site, and the point was later the estate of Jacques Baby, a prominent landowner and government official.

The boundary includes three City-owned parks that were donated by Home Smith to provide ample green space for the residents of Baby Point along the banks of the Humber River.

The Old Millside neighbourhood is not being recommended for designation.

Heritage attributes are the physical, spatial and material elements within the district that convey its heritage character and that should be conserved. They include buildings, streets and open spaces that are a collective asset to the community. Heritage attributes can range from physical features, such as building materials or architectural motifs, to overall spatial patterns, such as street layout and topography.

These attributes are important features that convey the history of the district, from its indigenous use through to its development as a planned garden suburb

These attributes support a sense of place, defining the context of Baby Point and its community values

These attributes reflect the design of Baby Point as a garden suburb, guided by a set of principles that informed the streetscape and architecture of the neighbourhood

These attributes represent valued and unique natural resources that reflect the history of the district and contribute to a sense of place

Properties within the Baby Point HCD were individually evaluated to determine whether they contribute to the neighbourhood’s heritage value. Contributing properties are those that have design, historic and/or associative value and that contribute to the neighbourhood’s heritage character. Properties were identified as contributing if they satisfied the following criteria:

The Baby Point Heritage Conservation District Study includes the following components:

The Baby Point Heritage Conservation District Study and staff report are posted above.

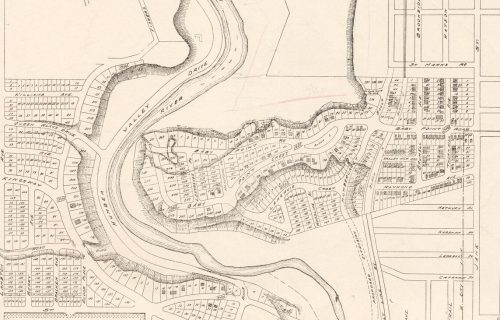

The Baby Point and Old Millside neighbourhoods together constitute a unique geographic area within the City of Toronto, located on the eastern banks of the Humber River at a point where the river makes a natural oxbow formation, resulting in a peninsula-like shape. Baby Point is primarily located on a plateau overlooking the river, while Old Millside is on the southern slopes of the plateau and at a much lower elevation.

The Study Area has an extensive history dating from as early as 6,000 BCE to the present-day. It has been the site of seasonal and year-round occupation by indigenous communities, was the estate of a leading member of Upper Canada’s Family Compact, and is one of Toronto’s early and most comprehensive examples of a Garden Suburb. These histories in part support the value of Baby Point to local residents and the broader community, and have contributed to the neighbourhoods’ unique sense of place.

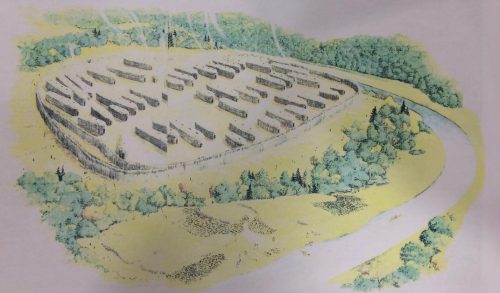

The village of Teiaiagon, which translates to “it crosses the steam”, was a village that was occupied in the 17th century by members the Seneca Nation, whose homelands were to the west of the Finger Lakes in upstate New York. The village is believed to have been established as a permanent settlement by 1673, however the area is known to have been used by indigenous communities dating back to at least 6,000 BCE.

Teiaiagon most likely consisted of 20-30 longhouses, supporting a population of between 500-800. The village’s location was highly strategic – it could be easily defended from its location atop the peninsula overlooking the Humber River, and would have had access to the abundant salmon of the river and surrounding agricultural fields.

Following the retreat of the Seneca in the 1680s due to increased military pressure in their homelands, the village site was occupied by the Anishnaabeg who were extending their homelands south from the upper Great Lakes. Baby Point was a strategic site on the Carrying Place Trail for the Anishnaabeg, however increased European military pressure and settlement activity in and around Lake Ontario through the 18th century saw the decline in use of the village site for seasonal hunting and trading purposes.

Baby Point takes its name from James Baby (1763-1833), a prominent French-Canadian merchant and early resident of the Town of York. Baby was a member of the “Family Compact”, a term used to refer to the ruling elite of Upper Canada from 1810-1830 and included recognlizable names such as John Robinson, Bishop Strachan, William Osgoode and Aeneas Shaw. Baby was notable not only for his conributions to the early Town of York, but for being the sole French-Canadian and Catholic in the otherwise Anglican group.

In the early 1820s Baby purchased 1500 acres along the eastern banks of the Humber River, and constructed a house to the west of Cashman Park, surrounded by orchards of fruit-bearing trees. The estate was passed on to his sons Raymond and James, and remained in the Baby family through the 19th century.

Baby Point and to a lesser degree Old Millside owe much of their present-day appearance to Robert Home Smith, a lawyer and entrepreneurial developer from Stratford, Ontario who purchased extensive tracts of land along the Humber River with a vision of creating attractive and healthy residential suburbs on the outskirts of the growing city. Home Smith was a proponent of the Garden Suburb approach to neighbourhood development, defined by picturesque streets that followed natural landscape features, homes designed in English revival styles, landscaped yards and access to parks, a valuation of private space and design restrictions to preserve the natural and built character of the neighbourhood.

Construction in Baby Point began in 1913 and continued through the ’20s and early ’30s. Newspapers from this time reported the discovery of human remains during construction, indicate the presence of multiple grave sites and previous settlement. The Baby Point Club and Humbercrest United Church – two significant community assets in the area – were also developed at this time with the support of the local community, reflective of the neighbourhood’s close social connections.

When the design restrictions put in place by Home Smith expired in 1941, residents petitioned the local government to adopt a by-law that enforced many of the same design restrictions following the principles developed by Home Smith and supporting the neighbourhood’s designed character as a picturesque garden suburb of houses nestled in a park-like setting. The by-law guided development in Baby Point through the latter half of the 20th century.

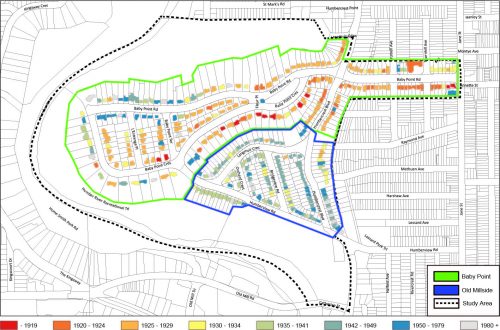

A character analysis of the study area was undertaken in order to understand the defining features of Baby Point and Old Millside, and determine whether those features relate to and still reflect periods of development. This analysis included the mapping of information compiled through the built form survey, including dates of construction, building height, and architectural style, which enabled the team to identify patterns and trends within the study area and begin to identify character-defining features.

The purpose of the character analysis is to determine if portions of the study area contain a consistent heritage character, and if so to identify what features are required to support this character in the long-term.

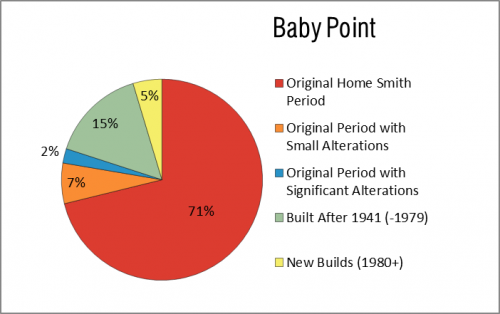

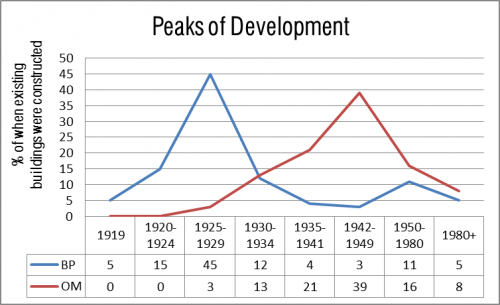

An analysis of dates of construction of houses in the study area was undertaken in order to determine not only the age of the existing buildings, but to identify major periods of development. Research determined that construction in the Baby Point neighbourhood peaked between 1925 – 1929, and that approximately 80 per cent of the neighbourhoods’s current houses were built by 1934.

This period of development aligns with the time during which designs for new houses had to be approved by the Robert Home Smith Company (1911-1941) and had to abide by certain design restrictions. This supported high quality house designs that were compatible with the neighbourhood and it’s park-like setting in terms of materiality, architectural style, placement and landscaping.

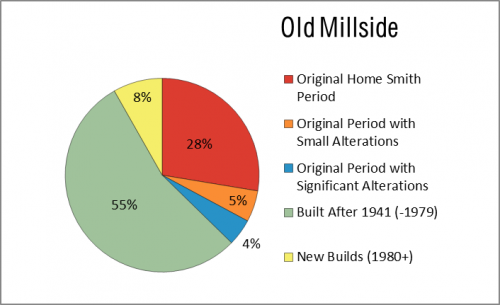

In contrast, construction in Old Millside peaked in the late 1940s, after the design restrictions that were put in place by the Robert Home Smith Company expired. This later peak of development reflected in the more regular placement of houses in Old Millside, which are generally smaller and resulted in greater land disturbance than houses in Baby Point.

The study area includes a variety of early to mid-20th century architectural styles, interspersed with contemporary buildings which range from traditionalist to modern.

The Baby Point neighbourhood is fairly consistent in style owing to its substantial development during the Home Smith Building Period (1911-1941) and associated design regulations. Most houses in Baby Point were designed in the English Cottage / Tudor Revival style (34 per cent) or the Colonial Revival style (35 per cent), two architectural styles that were popular in garden suburb neighbourhoods and reflected ideas of domesticity, craftsmanship and the picturesque.

The Old Millside neighbourhood has a greater variety of architectural styles owing to its longer and later period of development (1940s – 1980). The neighbourhood contains examples of both the English Cottage/Tudor Revival and Colonial Revival styles, however it also has examples of the Minimal Traditional style (15 per cent) that was popular in the post-war period and reflected modern architectural sensibilities.

Public realm is used to refer to the space around and between buildings that is publicly accessible (streets, sidewalks, parks). Alongside private landscapes (i.e. front yards), the public realm often contributes to a neighbourhood’s overall character. The public realm and private landscapes of Baby Point and to a lesser degree Old Millside owe much of their appearance to the study area’s Garden Suburb roots, where curvilinear roads that followed the contours of the land provide new perspectives at each turn, and buildings have generous setbacks creating expansive green spaces.

Houses that back onto the escarpment tend to have the largest setbacks, whereas properties on inner blocks and with less square footage are set more closely to the road. An increased sense of space and feeling of being immersed within a park-like setting can be experienced traveling from east to west along Baby Point Road and Crescent as you approach the escarpment edge.

One key aspect of the Home Smith Building Period was to limit excavation, landscape modification and tree removal in Baby Point in order to preserve the natural environment, including the topography and trees. In contrast, Old Millside was developed after the restrictions were lifted, resulting in a more modified landscape with fewer mature trees. Setbacks in Old Millside are generally more homogeneous than in Baby Point.

Integrity refers to how well a property is able to illustrate its heritage value, based upon physical features that relate to a specific period of time, association or event. For example, a building valued for its Colonial Revival design could have integrity if it retains features that relate to Colonial Revival architecture, such as a centre doorway flanked by bays with symmetrical windows. A building could still have integrity despite subsequent alterations or additions.

Following an analysis of dates of construction and architectural styles, the consultant team determined whether houses constructed during the Home Smith Building Period (1911-1941) have sufficient integrity in order to reflect the design principles associated with this period of development. This was done in part by evaluating the degree of visible alterations to each house, taking into consideration architectural details, building materials, and additions.

78 per cent of the houses in the Baby Point neighbourhood constructed during the Home Smith Building Period appear to have had few to no visible exterior alterations, and continue reflect the neighbourhood’s garden suburb design principles. In contrast, only 33 per cent of the properties in Old Millside reflect this period of development, with greater variety in architectural style and features throughout the neighbourhood. The majority of houses in Old Millside (63 per cent) were built post-war.