In February 1903, Ontario Premier George Ross (1841-1914) announced that the Syndicate’s Electrical Development Company had received the charter to supply electrical power from Niagara.

Prior to this, the premier had faced pressure from municipalities and manufacturers to change his policy toward energy to favour public interests. As far back as 1897, Toronto City Council had investigated the costs for building a municipal plant to manufacture light and power for the city in competition with the private interests of the Syndicate. This investigation did not result in actual development, and council shifted its attention to hydro power.

By 1902 Council’s bids to the province to establish a municipally-owned public utility to provide Toronto with power from Niagara had been turned down four times. Other municipalities also were interested in acquiring cheap hydro power, and were united in the desire to prevent control over electricity from falling into the hands of a private monopoly.

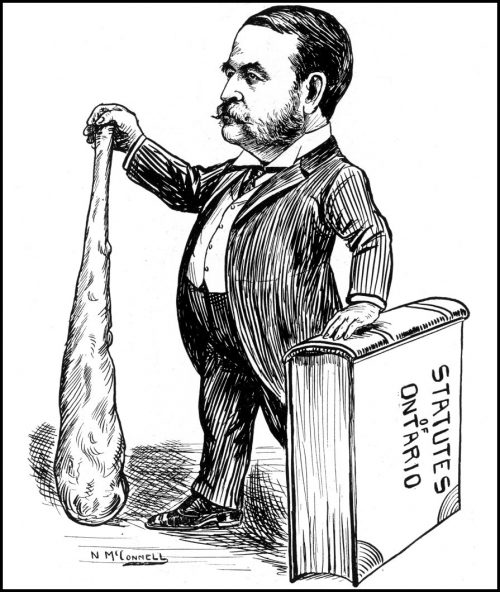

The frustration of the municipalities and manufacturers of south-western Ontario led to an historic meeting on June 9, 1902 in Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario. This group of civic leaders and businessmen was led by Toronto Alderman F.S. Spence, who was a consistent champion of the complete ownership of electrical distribution systems by municipalities. Spence proposed that the municipalities should unite in asking the Ontario government to appoint a government commission to manage the transmission of power to Ontario towns and cities, which would buy the energy from the provincial commission.

Alderman Francis Spence is shown to the left of the mayor, holding a book in his hands. Spence is credited with being a key figure in the founding of the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario.

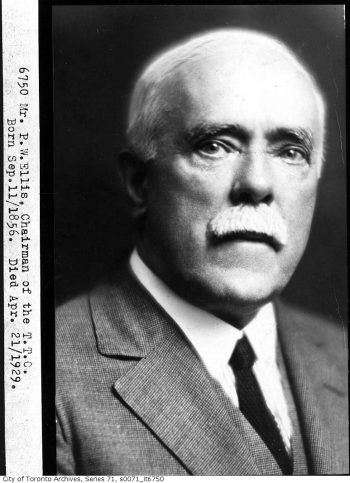

In addition to Spence, the group of municipal leaders included Toronto businessman P.W. Ellis (1856-1929), who was a good friend of M.P.P. Adam Beck (1857-1925). Ellis endeavoured to interest his friend in the question of hydro-electricity, and Beck joined the group in 1903.

In January of 1903, Toronto council made its own application to the province for the right to generate and transmit Niagara power to Toronto, but the application was refused by Premier Ross. After this, Toronto threw in its hat wholeheartedly with the other municipalities, and again approached the premier.

Ross was facing voter discontent with his administration and an increasing number of pointed questions from the leader of the opposition, James Whitney (1843-1914), and therefore was more open to the lobbying of the group of municipalities.

In June of 1903, an act for the Construction of Municipal Power Works and other Power and Energy was passed. This act allowed the municipalities to appoint a commission known as the Ontario Power Commission, to investigate and report on the supply and distribution of power. The Commission began its three-year study on August 12, 1903.

In 1905, James Whitney succeeded Ross as Ontario’s premier, and he included Adam Beck in his cabinet as Minister without portfolio. Beck’s consuming interest by this time was hydro-electricity, and as a lobbyist for public ownership of utilities, he had the distinct advantage of being a close advisor to the premier.

After Premier James Whitney was elected in 1905, he declared that the hydro-electricity produced by Niagara “should be as free as air.” Whitney appointed Beck as a minister without portfolio in his government, and Beck’s only true concern while he was a minister was the development of hydro power for the people of Ontario.

The municipalities continued to agitate for cheap power, and in 1906, 1,500 delegates marched from Toronto City Hall to the Ontario Legislature to present a resolution calling for government action. This resulted in the passage in 1906 of the act, To Provide for the Transmission of Electric Power to Municipalities, which was drawn up by Adam Beck. This act created an administrative body called the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario (HEPCO), with Adam Beck as chairman.

On January 1, 1907, a Toronto by-law was passed, permitting City Council to enter into a contract with HEPCO for the delivery of power to Toronto at a price not exceeding $18.10 per horsepower per annum. In 1907, the 1906 act was repealed and replaced by the Power Commission Act. The provincial commission became, in effect, the wholesaler of hydro-electric power, while the municipalities were the retailers.

All of this activity was very worrying to the Syndicate of Nicholls, Pellatt and Mackenzie, owners of the Toronto Electric Light Company and the Electrical Development Company. The Syndicate had its own supporters, including several hundred shareholders, who were men in high social and business positions, and owners of loan and financial companies.

However, the ideology of public control proved very compelling, and opinion turned against the concept of private monopolies controlling what was considered a public asset. Ultimately, this ideology, along with Beck’s promises of lower costs, better service, and accountability to customers, rather than shareholders, spelled the beginning of the end for the private interests.

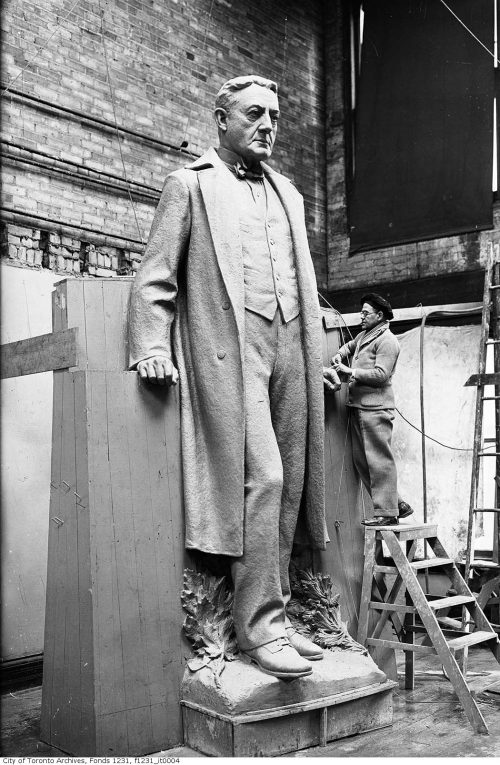

Artist Emanuel Hahn is shown putting finishing touches on his statue of Adam Beck. The statue is located on University Avenue at Queen Street West, and was jointly erected by City of Toronto and the Toronto Hydro-Electric Commission in 1934.

Back to introduction

Next page – Toronto Hydro-Electric System