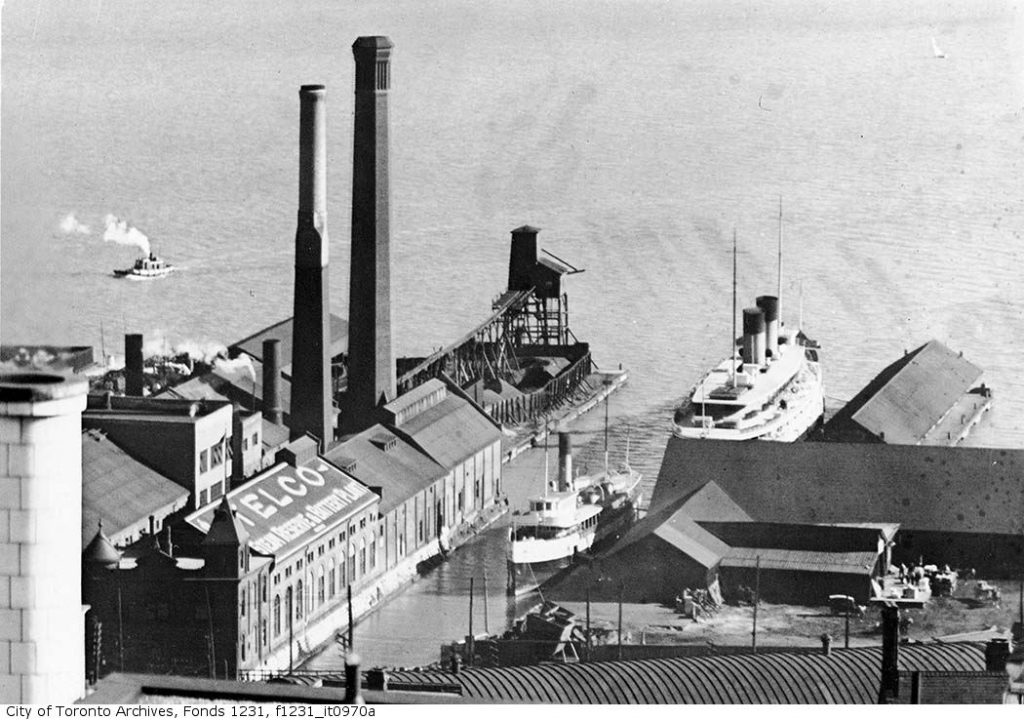

J.J. Wright’s Toronto Electric Light Company (TELC) was successful in attracting customers, and by 1886 had expanded its generating capacity by constructing a massive new plant at the foot of Scott Street. Their coal-fired plant had ten 100-horsepower boilers, which drove two pairs of steam engines of 500-horsepower each. The engines were connected by belts to the dynamos that generated the electricity.

In this photograph of the TELC plant, the large piles of coal required to fuel the steam engines are visible at the end of the Scott St. dock.

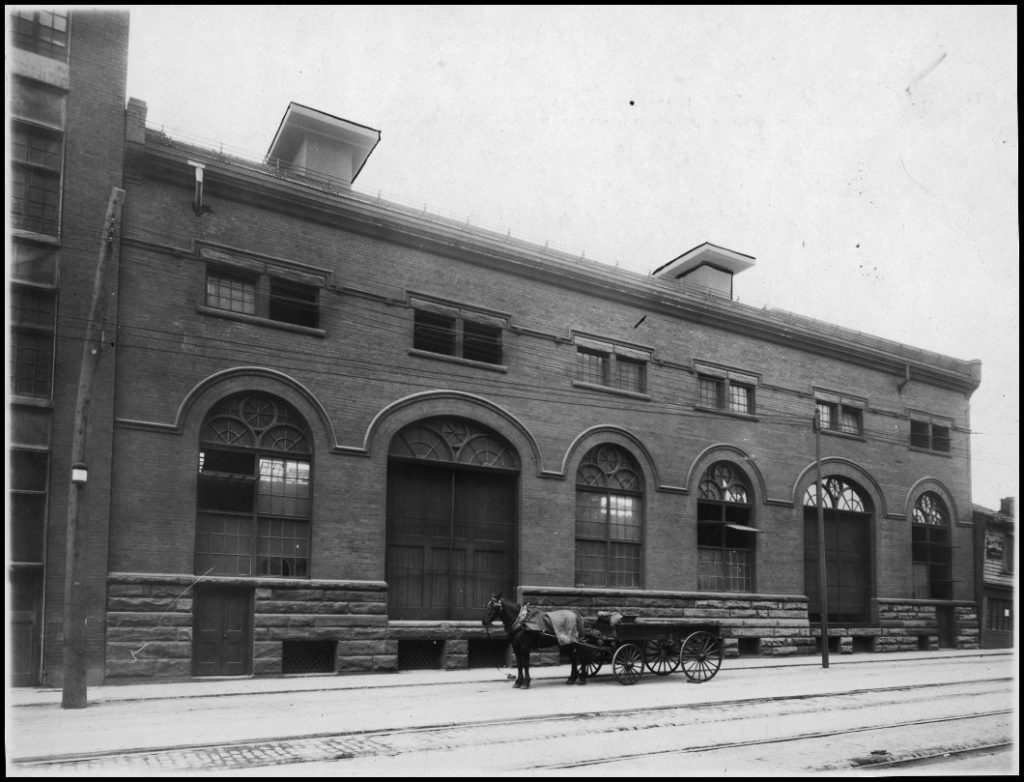

A new player arrived on the scene in 1889 with the Toronto Incandescent Electric Light Company (TIELC), which was formed by manufacturer Frederic Nicholls (1856-1921). The incandescent bulb was patented by Thomas Edison in 1879, and TIELC held the Canadian rights to Edison’s patents. TIELC also used the Edison tube underground system for the underground distribution of power. TIELC generated its power at its Terauley (later Bay) Street station.

This substation was originally operated by the TIELC, but was eventually taken over by the THES. It still exists on the west side of Bay Street, north of City Hall.

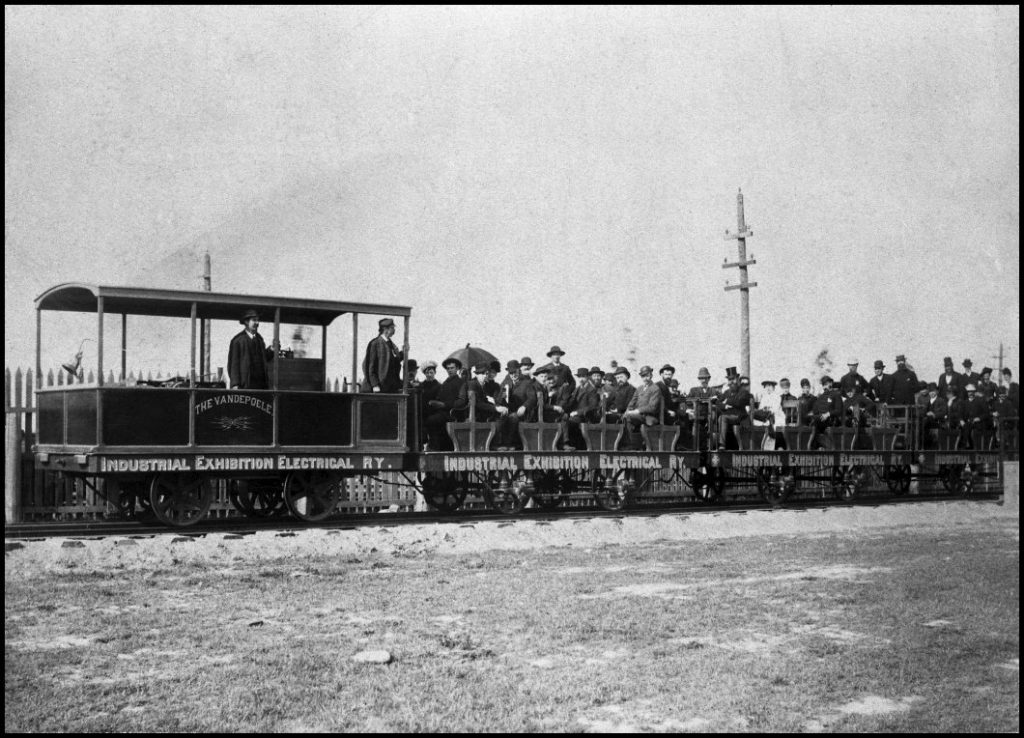

Street and indoor lighting was not the only market for electricity in Toronto at the end of the 19th century. Another major consumer of power was the electric street railway. J.J. Wright had demonstrated the potential of the street railway to visitors at the Toronto Industrial Exhibition in 1883. He and American expert Charles Van Depoele improved upon their demonstration the following year, and 50,000 visitors to the 1884 exhibition enjoyed a one-mile journey through the grounds on an electric railway using a trolley-pole and overhead wire.

This photograph shows a motorized Grand Trunk flatcar, which had been fitted with seats for visitors to the exhibition. While J.J. Wright brought the first electric railway to Canada, its short journey of one mile on the exhibition grounds made it more of an amusement than a practical form of transportation.

Although it may have seemed that TIELC would be in competition with the Toronto Electric Light Co., in practice the two companies served different markets. The incandescent bulb was better suited to indoor lighting than the arc lamp, especially in smaller rooms in offices and homes. Nicholls’ company was more in competition with Consumers’ Gas, but since it cost about the same to light your room with gas or electricity, a small but steady stream of customers made the switch to electricity.

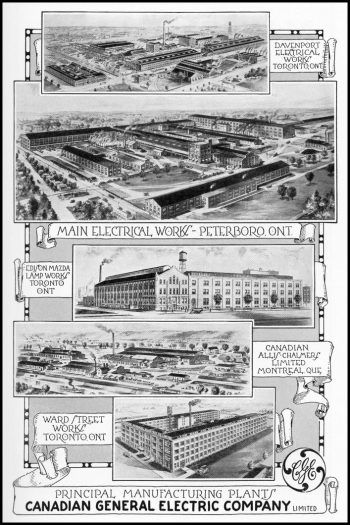

Frederick Nicholls was also interested in using his technical expertise to manufacture electrical equipment and appliances. He assumed management of the Canadian General Electric Company in 1892 and served as its first president. In 1896 the Toronto Electric Light Company took over TIELC, bringing together the dynamism of Frederic Nicholls and the financial genius of stockbroker Henry Pellatt, who later used some of his accumulated wealth to build his fabulous personal castle, Casa Loma.

It would be a few years before Toronto would see more widespread use of the electric street railway. William Mackenzie (1849-1923), formed the Toronto Railway Company (TRC) in 1891, and he won a thirty-year charter to operate the city’s street railways. Until that time, the street railways had employed horse power, but in August of 1892, TRC electric streetcars went into operation.

The trio of Frederick Nicholls, Henry Pellatt and William Mackenzie became known to both friends and foes as, “The Syndicate.” Together they combined all the elements necessary to be successful. Nicholls provided the manufacturing strength, Pellatt was a major force on the Toronto financial scene and Mackenzie provided a key market for electrical power – the electric street railway. Throughout the 1890s the Toronto Electric Light Company and the Syndicate continued to dominate the market and overcame all competition from smaller electricity companies.

They also contended with their most serious rival, Consumers’ Gas, by reducing the price of home electricity by one third in 1897. However, a serious vulnerability of the Syndicate was revealed in 1902 when Ontario was hit with a “coal famine.” Labour unrest in the United States halted all shipments of Pennsylvania coal across the border, underlining TELC’s reliance upon expensive American coal to power its steam generating plant. The Syndicate began to look to hydro-electric power to deliver them from this dependence.

Back to introduction

Next page – Harnessing the Power of Niagara