Torontonians of diverse backgrounds and experiences contributed to war efforts in the First and Second World Wars, the Korean War, Afghanistan and in United Nations (UN) Peacekeeping missions. These contributions took various forms and many endured systemic barriers. While some served overseas at the front, others were engaged on the home front training pilots, producing statistics to support wartime planning and management, and working in munitions factories, among many other contributions. Here are some of their stories.

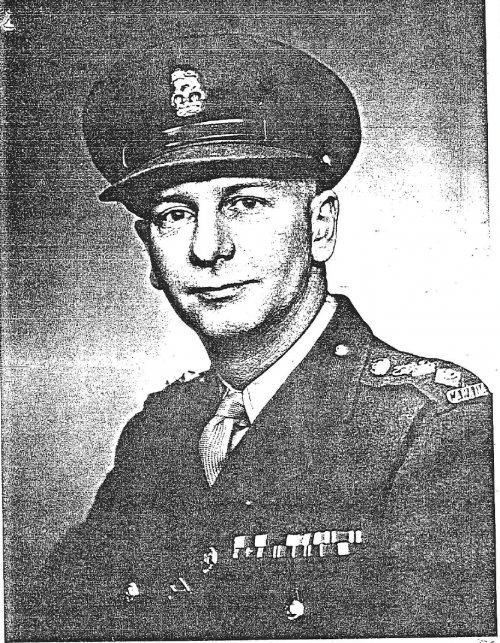

On the morning of August 19, Captain John Anderson was in charge of a landing craft with over 100 men on board. When it arrived on Puys Beach, the boat was heavily attacked. Thinking quickly, Anderson organized Bren gunners to return fire, even operating a gun himself. When the boat reached the shore, Anderson ensured the landing of all unwounded men as well as a three-inch mortar and its ammunition. Despite receiving a head wound caused by shell splinters during the initial gunfire, Anderson continued to motivate and direct his men until the end of the raid. He was later evacuated to England.

Captain John Anderson displayed unwavering selflessness by continuing to lead his men despite being injured. He was later awarded the Military Cross for his bravery.

Corporal, Loyal Edmonton Regiment

Died: February 12, 2010, age 24

Joshua (Josh) was born and raised in Scarborough, Ontario. He was known for his infectious laugh and sense of humour, his love of music and commitment to his family and friends.

After graduating from Winston Churchill Collegiate High School, Joshua left Ontario at age 18 with the intention of joining the Edmonton Police Service. Instead, he enlisted with the Loyal Edmonton Regiment (4th Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry). As a corporal he was part of the Kandahar Provincial Reconstruction Team in Afghanistan.

Tragically, Corporal Joshua Baker lost his life during a training accident in Kandahar City on February 12, 2010. He is buried at Pine Hills Cemetery in Toronto.

Memorials to this local hero appear throughout the neighbourhood where he grew up. There is a basketball court named in his honour at Ellesmere-Statton Public School in Scarborough; a weight room and mural in his memory at Winston Churchill Collegiate High School; and his name, “Cpl. Joshua Caleb Baker” was added to Canlish Road, Scarborough, street signs in a 2014 ceremony.

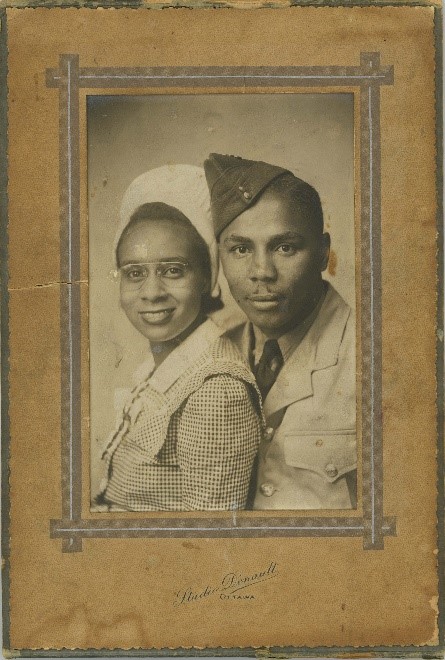

Signalman, Royal Canadian Corps of Signals

Died: February 27, 1941, age 29

Julius Baxter was a printer/typographer at the Toronto Daily Star. He had been promised his job when his active service ended.

While he was serving in the war, a Regimental psychiatrist recommended Julius(a Signalman) be discharged on medical grounds, but he was charged with desertion. Sadly, in his effort to prove his ‘unworthiness’ in seeking to be discharged, Julius ingested substances from the medical hospital and poisoned himself to death. He was one of the first casualties of the Second World War from Toronto.

He left behind a wife and two daughters aged 10 and seven, and a three-year old son. Memorial crosses were presented to his mother, Kate and his widow, Bernice.

This story demonstrates the emotional wounds that were also challenges of serving on the battlefield, and that occurred prior to a true understanding of mental health and traumatic stress disorders.

Signalman Baxter’s record is listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and the Service Files of the Second World War – War Dead, 1939-1947

Major in the Royal Canadian Air Force(RCAF) Women’s Division

In 1941, Norda Bennett began an honours program in Philosophy and English at the University of Toronto. She interrupted her studies in 1943 to join the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Her mother, Sophie Bennett, was also very involved in the war effort, serving as Vice-Chair of the Women’ s War Efforts Committee of the Canadian Jewish Congress.

The RCAF allowed women to join through the creation of the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force that later became the RCAF Women’s Division (WD). Prior to this time, women were only allowed to fill the role of Nursing Sisters in the RCAF Medical Service. In the Women’s Division, they were

permitted to fill support jobs. In 1946, the RCAF WD was disbanded and women were permitted to join the RCAF in 1951.

After Bennett was discharged in 1944, she resumed her studies at the University of Toronto where she was a reporter for the Varsity News and participated in the Player’s Guild.

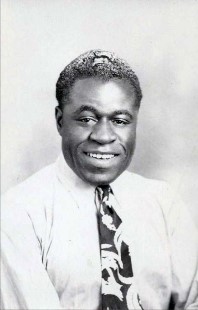

At 20 years of age, Leonard Braithwaite visited a recruitment centre at Bay and Wellington Streets once a month for four months in an effort to enlist, but was rejected every time by recruiting officers unwilling to accept Black Canadians into the Armed Forces. Leonard was eventually accepted when a new recruiting officer of Ukrainian descent accepted his application. The recruiting officer had shared with Leonard the experiences of Ukrainian and Polish people who had faced also faced discrimination when trying to enlist.

He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force as a Safety Equipment Operator, stationed overseas in England. He served with the No. 6 Bomber Command in Yorkshire, England as an engine mechanic and a safety equipment worker.

After the war, Leonard studied at the University of Toronto, Harvard Business School and Osgoode Hall Law School. Following a legal career he served as a Member of Provincial Parliament representing Etobicoke from 1963 to 1975, the first Black Canadian to be elected to the Ontario Legislature.

Leonard died in March 2012.

Lieutenant in the 4th Canadian Infantry Battalion who served in France

Died: April 24, 1915 at the 2nd Battle of Ypres at age 28

Cameron Daniel Brant (1887-1915), was a member of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation and was one of the first enlistees soon after war was declared in 1914. Commissioned a Lieutenant, Brant sailed for England in October 1914, completed training at Salisbury Plain, and was shortly after sent to France. A capable soldier and confident leader, Lt. Brant was killed leading his men in a counter attack at the 2nd Battle of Ypres on April 24, 1915.

To commemorate Brant’s service, a plaque was erected in the New Credit United Church and his name was etched on the New Credit Veterans Memorial. In 2014, the Mississaugas of the Credit Public Library received a call from the Picton Town Library with the offer of a book once owned by Cameron Brant. It was a book of poetry titled Songs of a Sourdough by Robert Service.

The inscription inside the book revealed Brant’s signature and proved it had once belonged to Brant. It was a precious addition to their collection. To learn more about this story, please see this video created by the City of Toronto Historic Sites: A Poetry Book Comes Home

Story courtesy of the Mississaugas of the Credit Public Library.

Lance Corporal, Royal Regiment of Canada

Died: August 19, 1942 at Dieppe, age 27

Meyer Bubis was from a large Jewish family of seven siblings, who emigrated from Russia. He attended Riverside Collegiate and enlisted in September, 1939.

He joined the army and was posted to Iceland. He participated in the first Yom Kippur service for servicemen stationed in Iceland in 1940. Others present at the service were soldier and fellow Torontonian Lionel Cohen, several British servicemen, and Jewish refugee families from Germany and Austria. Meyer sent a photo of the Service to his father, where he wrote on the back, “Pop, this is the first time in the history of Iceland that such a service has been held. Take care of this for me.”

Lance Corporal Bubis died in the raid on Dieppe, on August 19, 1942. His body located three months after his death, is buried in Dunkirk Town Cemetery in France. The Dieppe Raid resulted in the most Torontonians killed in the line of duty, than any other day in all wars.

His younger sister Esther, waited for her 18th birthday, a year after her brother was killed, to enlist and serve with the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. She was one of only 270 Canadian Jewish women to wear a uniform for Canada in the Second World War. Upon her return, she resided in Oakville until her death in 2018.

Meyer Bubis is listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and Ontario Jewish Archives.

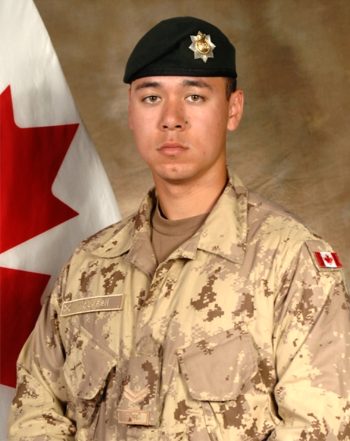

Corporal, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry

Died: July 3, 2009, age 30

Nick was born in Toronto and moved to the Buckhorn, Ontario area as a child. While attending Sir Sandford Fleming College in Peterborough, he enlisted and moved to western Canada.

After leaving the military to work in the Alberta oilfields, he rejoined in December 2007 enlisting with the Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry as a Corporal. A devoted family man,

Nick loved water sports and the outdoors.

On July 3, 2009, while serving his first tour in Afghanistan, he was Senior Commander of Brigadier-General Jonathan Vance’s tactical team. When travelling behind the General, he tragically he lost his life when the Light Armoured Vehicle he was driving struck a roadside bomb.

Many women worked on the home front doing vital jobs in various industries, such as working in munitions factories and shipbuilding yards.

The John Inglis Company munitions plant in Toronto was awarded a British-Canadian joint contract to produce 12,000 Bren light machine guns and by 1943 was producing 60 per cent of the global output of the guns. The plant also manufactured Browning Hi-Power handguns.

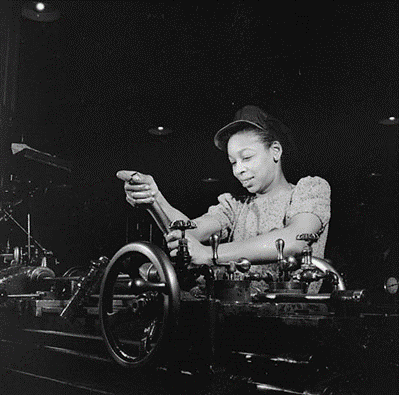

Cecilia Butler, a former night club singer and dancer, worked as a reamer in the small arms section of the plant. A picture of Cecilia at work was widely circulated by the National Film Board of Canada in its attempt to tackle work job discrimination against equity-deserving workers, including people of colour. The caption accompanying her photo, however, stated “Negro girl workers are highly regarded in majority of munition plants and display exceptional aptitude for work of precision nature.” This only perpetuated stereotypes and discrimination faced by people of colour, despite their contributions to the war effort.

The General Engineering Company (CECO) located in rural Scarborough produced military weapons, ammunition, equipment and stores. It hired women to work on heavy machinery, as well as handle gunpowder and explosives, including pouring TNT into shells. Operating 24 hours a day, six days a week from 1942 to 1945, the plant produced 256 million munitions.

Anne Wilmot Parkin worked in the high explosives area of the plant, filling No. 119 fuses. She worked with tetryl, a highly volatile yellow powder which had the ability to stain skin. The powder turned Anne’s skin and fingernails orange. Anne worked at GECO until the war ended.

Anne moved to Vancouver when she married. She passed away in 2016.

In 1914, Canada lacked both a professional military and a munitions industry. This gap was initially filled by volunteer soldiers and later by conscription, while the munitions shortage was addressed with makeshift facilities. The need for 18-inch shells for the Western Front was urgent, yet Canada lacked the necessary equipment and expertise, often leading to frequent failures in shell detonation.

To address these issues, the armament industry eventually employed 250,000 people, including 12,000 women, who were actively recruited to meet the demand.

At just 18 years old, at the British Munitions Supply Company factory in Toronto, Mary Campbell undertook the hazardous task of manufacturing shells for the British during the First World War. She, working alongside fourteen other women, undertook work which was perilous, involving exposure to high explosives and toxic chemicals, often leaving workers with jaundiced skin due to chemical exposure.

Campbell’s contributions were vital; by 1917, Canada was producing about a third of all British artillery shells. After the war, Canada faced the challenge of transitioning from a wartime to a peacetime economy as soldiers returned home.

Private in 78th Canadian Infantry Battalion (the Winnipeg Grenadiers). Served in France.

Died: March 15, 1954 at age 70 in Toronto.

Ethelbert ‘Curley’ Christian enlisted in the Canadian Army during the First World War at the age of 32. He served in France and fought in the Battle of Vimy Ridge, where he was injured by artillery fire that buried him in a trench. Christian was trapped in the trench for two days and all four of his limbs were crushed by debris.

While being carried from the battlefield, Christian again survived enemy fire when two of his stretcher bearers were killed. He developed gangrene and both arms and legs had to be amputated. He was discharged on September 3, 1918 at age 36 and moved back to Toronto where he underwent rehabilitation at Euclid Hall on Jarvis Street.

Ethelbert was well known for his advocacy for veterans. While he was in rehabilitation, Christian, along with his wife and the hospital director, appealed to the government and won an allowance for full-time caregivers of veterans who were wounded during the war.

He died in Toronto on March 15, 1954, at age 70 and is buried at Prospect Cemetery.

Telegraphist, Royal Canadian Naval Reserve, serving on HMCS Esquimalt

Died: April 16, 1945, at age 20

George Clancy was assigned to HMCS Esquimalt. That boat and her sister ship, HMCS Sarnia, were tasked with protecting a convoy of ships steaming to Scotland. With the war close to ending and the day calm, smooth sailing was expected off Halifax Harbour. While conducting its anti-submarine patrol, Esquimalt was torpedoed by a German U-Boat that ripped apart its hull. The ship sunk so rapidly that there wasn’t time to launch distress signals or release all the lifeboats, so many crew members perished in the frigid Atlantic while awaiting rescue. Of the 71 on board, only 27 survived. Sadly, George Clancy died at age 20.

He was lost at sea and is commemorated on a Halifax Memorial, one of the few tangible reminders for the men who died at sea. He was the son of Daniel J. and Mary E. Clancy of Woodside Ave. in Toronto.

George Clancy’s record is listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial . More information about HMCS Esquimalt is found through For Posterity’s Sake

, a Royal Canadian Navy Historical Project, and the Nova Scotia Military History – Madigan Stories

.

Sapper, 1 Combat Engineer Regiment, Royal Canadian Regiment

Died: July 20, 2010, age 24

Born in Toronto in 1986, Brian was raised in Bradford, Ontario and attended Bradford District High School. Following graduation, he joined the workforce before enlisting in the Canadian Forces in 2007.

He completed his basic Combat Engineering training at the Canadian Forces School of Military Engineering and was assigned to 1 Combat Engineer Regiment in November 2008 as a Sapper.

On his inaugural deployment to Afghanistan, he was injured and fought hard to return to his duties. Tragically, on July 20, 2010, he lost his life to an improvised explosive device while on a foot patrol in the eastern part of the Panjwaii District of Afghanistan.

Memorials to Sapper Collier appear on a memorial plaque at the Bradford West Gwillimbury Leisure Centre, a testament to his love of hockey. A street, near his childhood home was named “Brian Collier Way”.

Joyce Crook was born on Dillworth Crescent in East York in 1926. After the war started, many young men she grew up with were signing up to go overseas, filling the neighbourhood with uniformed soldiers. At school, Joyce and her classmates participated in making “bundles for Britain,” with each student knitting a seven-inch square that would be sewn into larger blankets for soldiers.

She was 16 years old in 1942 when soldiers landed on Dieppe. She still remembers an afternoon in early September when her mother mentioned a visit from the ice delivery man who told her that his only son had been killed during the Raid. That tragedy, and the tragedies of her neighbours stuck with Joyce over the years.

A decade later, Joyce decided to visit Dieppe on a trip to Europe. Standing on the beach, she could picture the landing crafts carrying the men from her neighbourhood, and many other Canadians to the beaches of Dieppe.

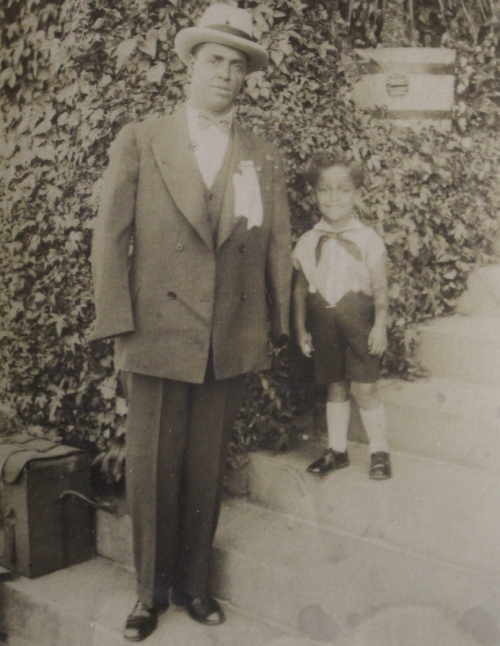

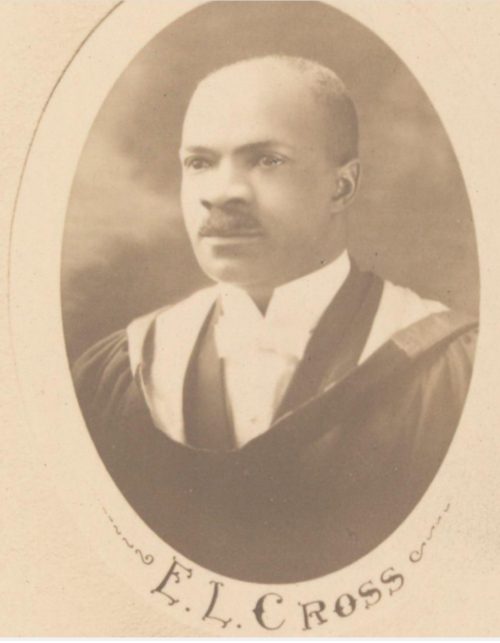

Born in Trinidad, Ethelbert Lionel Cross was a working journalist and Dalhousie University law student in 1917 when he enlisted in No. 2 Construction Battalion at the age of 27, in Halifax. During his two and a half years of service with the Battalion serving in France and England, he rose to the rank of Sergeant-Major.

Upon his return to Canada after the Battalion was disbanded in 1920, Cross continued his law studies at Dalhousie University and Osgoode Hall. He was called to the bar in 1924, becoming the fourth-known Black lawyer called to the bar in Ontario, and the first to establish a law practice in Toronto.

Cross was drawn to legal work in defence of other minorities and became well-known as a critic of racism and the then-official tolerance of illegal Ku Klux Klan activities. When Klan members held fiery demonstrations and terrorized a bi-racial couple in Oakville in 1930, Cross gathered support from Jewish groups and trade unions and galvanized public opinion to force the authorities to take action. The resulting court case was the first prosecution of its kind in Canada, and ended in a conviction.

A criminal lawyer, he left the practice of law in 1937, after encountering professional difficulties brought on by his open criticism of racist policies. He remained active in Toronto’s black and marginalized communities for the remainder of his life.

Dr. Jean Flatt Davey, OBE, OC: Chief Medical Officer, RCAF Women’s Division

Dr. Jean Flatt Davey was a trailblazing physician and the first woman medical doctor to become a commissioned officer in the Canadian Armed Forces Medical Branch.

Born in Hamilton in 1909, Dr. Davey studied at the University of Toronto, receiving her medical degree in 1936. She then practiced at Toronto General Hospital and Women’s College Hospital, eventually becoming medical advisor for women at the University of Toronto.

In 1941, Dr. Davey was one of the three women first recruited to join the newly formed Canadian Woman’s Auxiliary Air Force (CWAAF). Dr. Davey, along with her colleague Kathleen Oonah Walker, was responsible for selecting the first 150 members of the CWAAF. Shortly thereafter, the CWAAF was fully incorporated into the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) as the Women’s Division.

During this time, Dr. Davey was promoted to the position of Squadron Leader. In her new role, she was primarily responsible for the health and safety of the entire Women’s Division. She spent much of her time at headquarters in Ottawa but also toured the country to promote recruitment and conduct inspections.

Following her service in the Canadian Forces in 1945, Dr. Davey returned to Women’s College Hospital, where she eventually became chief of the medical department. Women’s College Hospital soon became affiliated with the University of Toronto, and Dr. Davey became the first Canadian woman to head a medical department at a teaching hospital.

She eventually became the Director of Medical Training at Women’s College Hospital, a position she held from 1965 until her retirement in 1973. In honour of her retirement, Women’s College Hospital established the Jean Davey Honorary Fund. As further recognition of her service, Dr. Davey was honoured with the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1943 and Order of Canada (OC) in 1973. She died in March 13, 1980, at the age of 71.

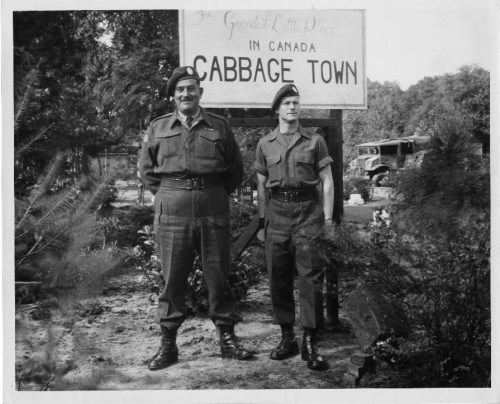

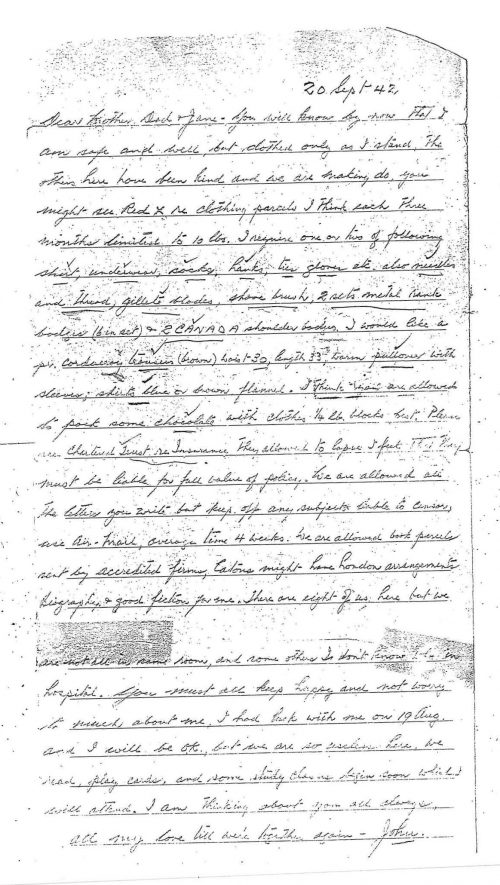

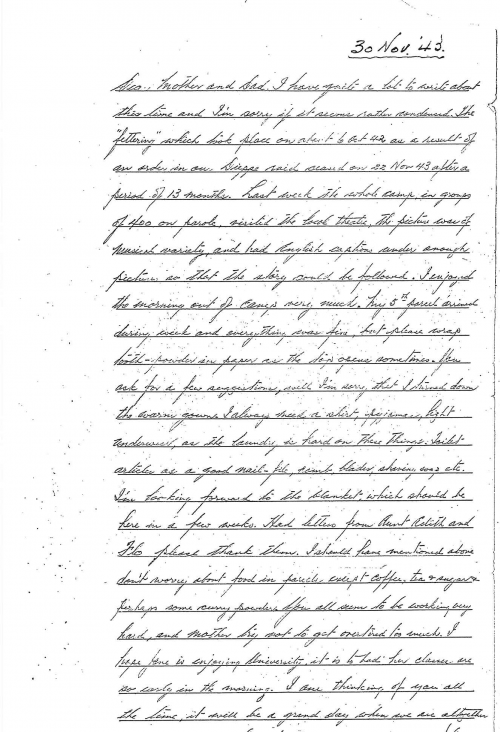

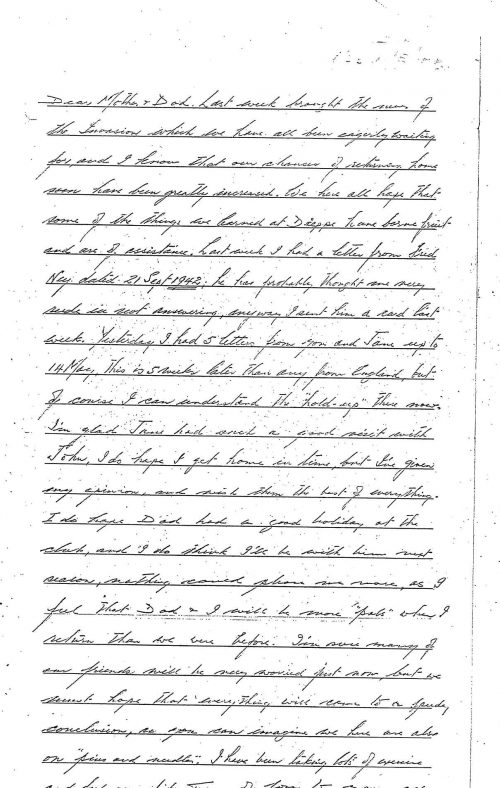

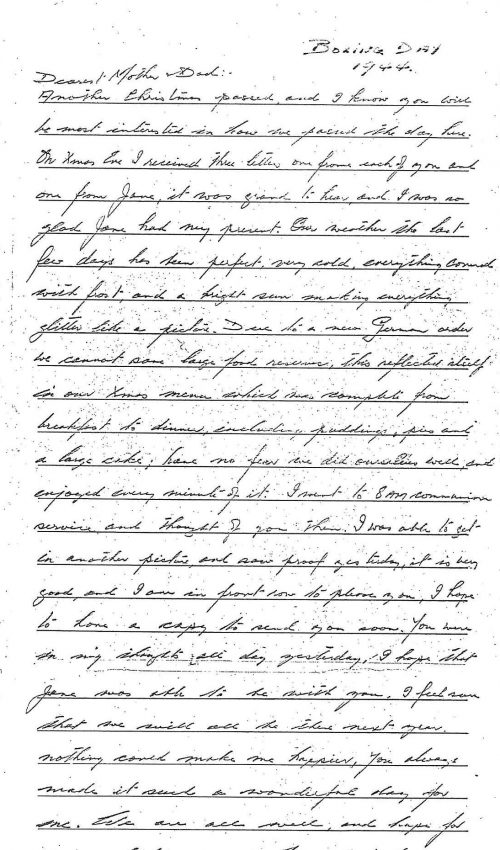

These four young men from Toronto enlisted with the Royal Regiment of Canada (RRC). They would go on to train together, fight together at Dieppe and were ultimately taken as Prisoners of War (POW) together. They endured harsh conditions as POWs and survived, but they carried haunting memories of the experience for the rest of their lives. Following their liberation, all four men returned to Toronto to build their lives and were once again reunited as police recruits for the Metropolitan (Toronto) Police Service.

Lance Corporal Campbell H. (Harry) Brown was born in Toronto and enlisted in 1940 at the age of 18. As his group arrived in the landing craft in the second wave, every soldier was killed before stepping foot off the boat, except for Campbell and the man to his left. He made it to the seawall uninjured until the surrender.

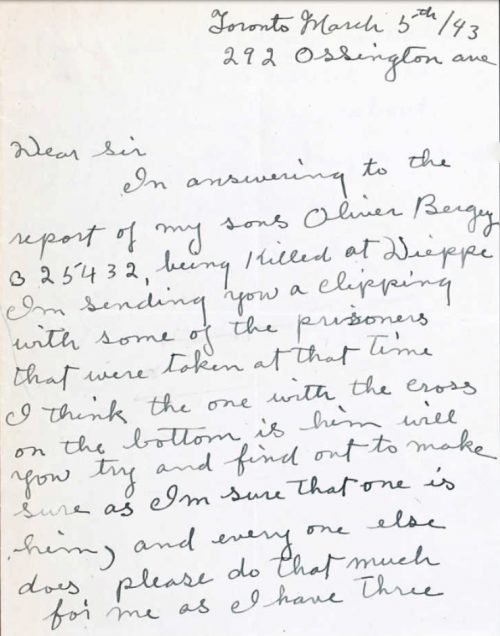

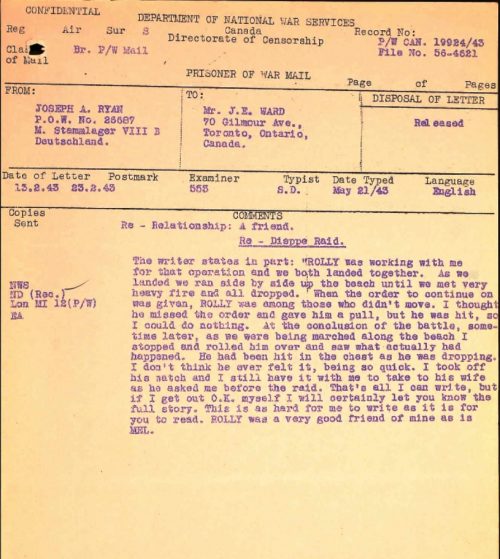

Lance Corporal James Duncan Donald was born in Toronto in 1920, enlisting in early 1940. He trained in Toronto and at Base Borden before departing overseas. In the first wave at Blue Beach, he was one of the few that made it up the wall where he was ultimately captured. He witnessed many friends die on the beach and attended to injured soldiers as best as he could.James wrote home following his capture and spoke about close friends from Toronto that he had seen killed as they stepped off the carrier. The letter ended up serving as a death certificate for those friends.

Private William Carson Olver was born in Toronto in July of 1919. He enlisted when the war broke out in 1939. William arrived in the first wave at Dieppe and was the first member of the Regiment to land at Blue Beach and reach the seawall. Hear an account of this story.After blowing a hole in the wall, Olver gained access to the upper promenade of the beach, where he became trapped for about an hour.

Unable to proceed further, he returned to the beach where he was subject to heavy fire until the surrender a few hours later. Listen to an interview with Private Carson’s son John Oliver.

Sergeant Charles Edward Surphlis was born in Toronto in 1920 and he was already a member of the Royals when the war broke out, having joined them at the age of 16. He was part of the second wave on Blue Beach and was able to make it to the seawall. When he got to the wall, Charles (or Charlie) was shocked when a man who had been jumping back down the wall, landed directly on top of him: it was Private Olver.From that point on, Surphlis and Olver stayed together until they were liberated. Hear about this Landing at Dieppe from his son Doug Surphlis and learn more about his father.

After the allies surrendered, all four of these men were taken to the same German Prisoner of War camp- Stalag VIIIB in Lamsdorf, the largest camp in Germany. Conditions in the camp were harsh and prisoners were shackled, had a lack of food and had no showers. They had to use the rain to cleanse themselves. They also had no privacy and were subject to frequent searches where their belongings were tossed from the bunks. They were required to perform manual labour for over two and a half years.

In the Winter of 1945, the Germans under threat of losing the war, began marching prisoners across Europe in what was known as The Death Marches. Listen to an account of the Death Marches. These marches went on for months with little food and harsh conditions and many did not survive. Allied planes caused chaos as they would shoot at them thinking they were enemy soldiers. They prisoners then had to scramble to find cover. During one of those raids, Campbell Brown and a few others managed to escape. After spending 33 months as prisoners of war, Olver, Donald and Surphlis were liberated by Allied forces in April 1945.

Once liberated, the four men, and many like them, had to recover from years of poor nutrition and illness and the physiological trauma that was rarely discussed at that time. After returning to Canada and life in Toronto, they were shocked to see each other at the Police Academy for the first time since the war. They had each joined without knowing that the others had joined as well. Each of the four men went on to have policing careers that spanned more than 30 years.

Despite the unspeakable horrors of Dieppe, the years at the Prisoner of War camp and the haunting memories they were left with, these four men developed an unbreakable bond and a friendship that lasted a lifetime.

Private, 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment

Died: December 5, 2008, age 24

Demetrios Diplaros was born on November 21, 1984, in the former Borough of East York. He attended Timothy Eaton Business and Technical Institute in Scarborough and was remembered by friends as a comedian who excelled in school and loved to play hockey.

He enrolled in the Canadian Forces in December 2005 and following basic infantry training, joining the 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, as a Private.

Demetrios was on his first operational tour as part of Operation Athena in Kandahar, Afghanistan on December 5, 2008, when he tragically lost his life as a result of hitting an improvised explosive device in his armored vehicle during a joint patrol with Afghan National Army soldiers.

Private Diplaros is buried in Resthaven Memorial Gardens in Scarborough.

Lieutenant Carola Douglas

Nursing Sister, Canadian Army Medical Corps – HMHS Llandovery Castle

Died: June 27, 1918 at the age of 31

Lieutenant Mary Agnes McKenzie

Nursing Sister, Canadian Army Medical Corps – HMHS Llandovery Castle

Died: June 27, 1918 at the age of 38

Lieutenant Carola Josephine Douglas was born in Toronto in April 1887. She graduated from Harbord Collegiate before becoming a nurse. In 1915, she volunteered to enlist in the Canadian Army Medical Corps, and was sent overseas to assist in hospitals in France. After working in hospitals near the front lines for several years, Lt. Douglas became a patient herself suffering from exhaustion. She was assigned to HMHS Llandovery Castle – a floating hospital – ferrying wounded soldiers from Europe back to Canada.

Lieutenant Mary Agnes McKenzie was also born in Toronto, in April 1880. She graduated from Rochester General Hospital’s Nursing School in 1903. She volunteered for service in Toronto on January 31, 1916 and was also assigned to HMHS Llandovery Castle.

On the night of June 27, 1918, HMHS Llandovery Castle was torpedoed by a German U-boat off the coast of Ireland. The vessel was bound for Liverpool after having returned wounded soldiers to Halifax. Although targeting a hospital ship was strictly against international law and despite Red Cross markings on either side of it, the ship was struck and sank within minutes. Many of the initial survivors of the torpedo hit were then shot down by the U-boat as they tried to escape in lifeboats.

The sinking of the Llandovery Castle was one of the deadliest Canadian naval episodes of the First World War. Of the 258 people on board only 24 survived the disaster by a lifeboat. Lts. Douglas and McKenzie were among the 14 Nursing Sisters on the vessel when it was struck. All 14 women were casualties along with some 200 other passengers; doctors and military personnel among them.

In the final 100 days of the War, the sinking of the hospital ship became a rallying cry for Allied forces, particularly Canadians. This tragic incident has been memorialized through plaques and an opera that debuted on the centenary of the disaster.

Story Curated by Francesco Bori, Legion Experience Museum

Served as Major in the Second Battalion of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada in France.

Ben Dunkelman was born to David and Rose Dunkelman, Polish-Jewish immigrants who founded Tip Top

Tailors. When the Second World War began, Dunkelman attempted to enlist in the Royal Canadian Navy. Due to

antisemitism he experienced there, he instead joined the 2nd Battalion of the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada.

Dunkelman served on D-Day, in the second wave at Normandy, on June 6, 1944. He also fought in campaigns in northern France, Belgium,

the Netherlands, and Germany. For his service, Dunkelman earned numerous commendations and the Distinguished Service Order for his service in the Hochwold campaign. After the war, he joined other Jewish veterans in fighting in the first Arab-Israeli war.

When Ben returned to civilian life in Toronto, he worked as an entrepreneur, art gallery owner, restauranteur, and co-founder of the Toronto Island Yacht Club.

He died in 1997.

Served as a Corporal in 3rd Battalion Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, in Afghanistan

Died: April 17, 2002 at age 24, as a result of a friendly-fire incident

Ainsworth Dyer grew up in Toronto and enlisted in 1997. In 2000, he was a member of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, who served in peace support efforts in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

In 2002, Dyer was deployed to Afghanistan, where he lost his life at the age of 24 in a friendly fire incident. He was buried with full military honours in the Necropolis Cemetery in Toronto. The Royal Canadian Legion named his mother, Mrs. Agatha Dyer, the 2004 National Silver Cross Mother.

Private and First Nation First Nation Code Talker, Canadian Army during the Second World War

Ernie Edgar, member of the Mississaugas of Scucog Island First Nation, enlisted in the Canadian Army in 1942 at age 20. Racially biased recruitment policies limited Indigenous people from entering the Royal Canadian Air Force and Royal Canadian Navy until 1943.

That same year, the U.S. and Canadian military began recruiting Indigenous soldiers to use their native languages to disguise Allied communications. Ernie was called upon as an Ojibwe code talker in Europe. Code talkers translated vital information about Allied forces, including orders for troop movement and the identification of supply lines or aircraft that were to carry out bombing runs. Code talkers translated the messages into their Indigenous languages before they were sent to battlefields in Europe, where another code talker translated them back into English and sent them to military commanders.

Indigenous North American languages were used because they were unique and distinct and, in many cases, had never been written down. Although their contributions remained hidden until recently, in part because the code talkers were sworn to secrecy, their service helped protect the Allies and win the war. Indeed, the Allies’ enemies were never able to break the code.

Following his discharge in 1945, Ernie went on to work at General Motors and became Chief of Scugog Island First Nation.

He died in November, 1987.

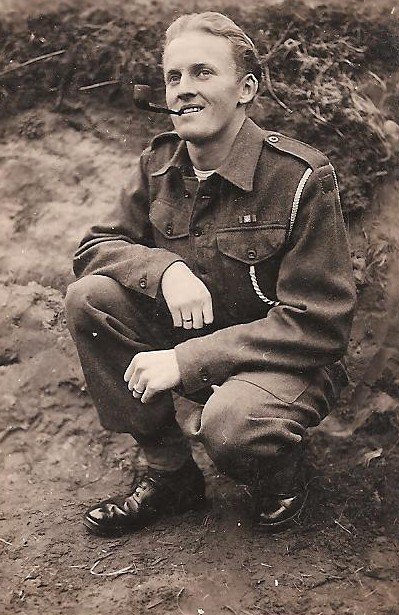

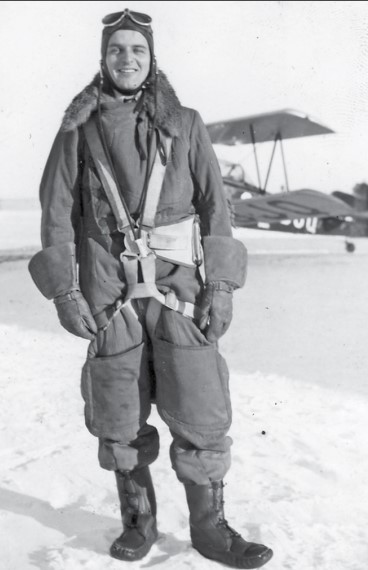

Flight Lieutenant Wally Floody, born April 28, 1918, in Chatham, Ontario. Floody’s early years were spent in Toronto, where his family relocated when he was one years old. Floody was a distinguished Canadian pilot who became a Prisoner of War during the Second World War.

Floody attended Northern Vocational School in Toronto starting in the fall of 1932, where at six feet tall in his senior year, he was a standout athlete, excelling in football and basketball. At 18 years old in 1936, he began working in sales for the Toronto Star, but his love for the outdoors led him to Northern Ontario’s gold mines. He worked at Preston East Dome Mines in Timmins as a “mucker,” shoveling rock and mud into carts for transport.

In 1938, Floody returned to Toronto where he met and married Betty Baxter. When Canada entered the Second World War in the fall of 1939, Floody enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

During his training under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, Floody became a pilot officer and was posted to RCAF 401 Squadron in England. There, he flew Spitfires until he was captured in October 1941 and became a prisoner of war. His wartime experiences included his pivotal role in the “Great Escape,” where he was instrumental in designing and constructing tunnels used in the escape attempt from Stalag Luft III.

After the war, Floody returned to Toronto on July 1, 1945. He was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for his wartime bravery. Floody remained active in the RCAF Ex-Prisoner of War Association and contributed to charitable causes, including the Canadian Cancer Society’s daffodil fundraising campaign.

Wally Floody passed away on September 25, 1989, in Toronto at the age of 71. His remarkable story was chronicled in Anton Gill’s “The Great Escape,” and he was honoured at the Canadian premiere of the film adaptation in 1963. Floody’s legacy endures as a symbol of courage, resilience, and dedication.

Sergeant Morris Greenberg, Royal Regiment of Canada, died August 19, 1942, at age 24.

The day after the war broke out, Morris Greenberg enlisted with the Royal Regiment. During the Dieppe Raid, Greenberg was gravely injured but continued to assist numerous wounded soldiers, risking his own life to pull them

onto a landing craft. Originally listed as missing, he was then reported as Killed in Action at Dieppe at just 24 years of age.

He had been promoted to Sergeant prior to the Dieppe Raid and wrote to his mother that he had been urged to take an officer’s training course despite feeling he needed more experience as a soldier.

Morris, or Moe, worked as a tie cutter for a shirt and neckwear firm before the war. He was also active in the Jewish People’s Library and was a talented Yiddish poet. Greenberg left behind his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Greenberg and brother, Irving Greenberg.

Irving also enlisted shortly after the war broke out at age 17 and served with the 48th Highlanders. As part of an anti-aircraft battery unit in England during the war, he was credited with shooting down several enemy planes. Irving transferred to the Royal Regiment after Morris’s death.

The Royal Regiment established the Moe Greenberg Trophy. This annual award is given to the recruit whose performance was considered superior to all other recruits upon completion of training in the last year.

Private in the Highland Light Infantry of Canada

Died: September 19, 1944, age 21

Humphrey Holloway was born on September 29, 1922, in Toronto and lived with his parents, Egbert and Edith Holloway, who had immigrated to Canada from Barbados. He attended a public school in Toronto and also spent a year at technical school. Prior to enlisting, he worked as a shipper and stock keeper in Toronto.

At the time of his enlistment in1943, he lived with his family at

1224 Yonge Street.

Sadly, Humphrey Holloway died in battle at age 21 and is buried at the Calais Canadian War Cemetery in France.

His name is listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial .

Private in the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry and served in Dieppe, France

Died: August 19, 1942 in Dieppe, France at age 25.

Private Maxwell Jacob King was the son of Mr. Frank L. King, who served as a long-time Chief Councillor of the Mississaugas of the Credit.

Thirty -two band members from the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation enlisted, with five of them paying the ultimate price in the Second World War.

While overseas , Maxwell King wrote an article for the January 2, 1942 issue of “The Pine Tree Chief “, which provides some clues as to his motivation for service:

“Eight months ago today, about 10 am, a train loaded with Canadian soldiers pulled into Aldershot [England] and unloaded a battalion of wide-eyed cheering men. We had answered the call of adventure in our hearts and here we were with the first contingent of the second division. Up until this time war had meant glory to us. It was a grand feeling to walk down the streets in our nice new uniform. It gave us an aggressiveness which we had not known before.

We had heard lots of stones of the good times of those other soldiers (God bless them) who were youngsters like us twenty-five years ago. England was far away and we thought the war would be over before we got here anyway. While at Camp Borden we heard rumours that we were to guard Canadian shores. On out last leave we laughed and said good-by to our families. We were sure we would be home again in three or four months. We were overjoyed when they told us we were coming to England. We would see many sights we had heard about so many times before.

Seven months after his article was published, Private Maxwell was killed in the ill-fated raid on Dieppe on August 19, 1942, leaving behind his mother, widow, and young son Maxwell.

Story courtesy of the Mississaugas of the Credit Public Library

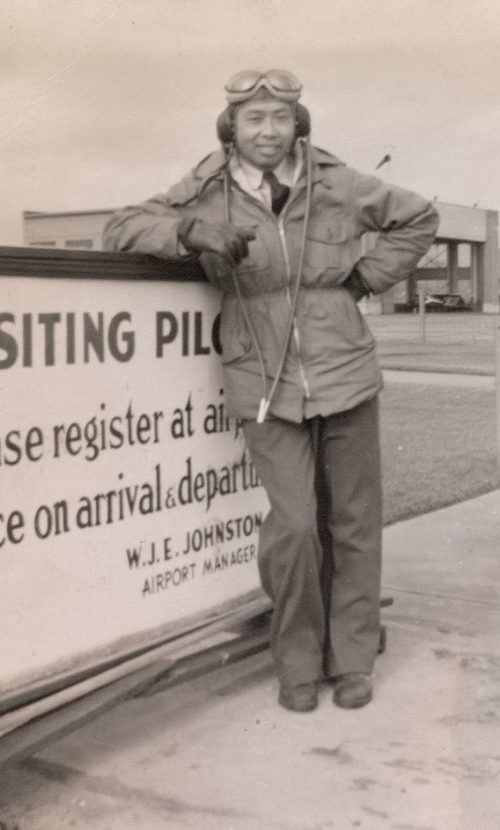

Jean Suey Zee Lee enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1942, the first and only Chinese-Canadian to be accepted into the RCAF’s Women’s Division during the war, a division of more than 17,000 women. She took her basic training in Toronto and served primarily at the Eastern Air Command RCAF depot in Rockcliffe, Ontario until the end of the war in 1945. Her brothers, Wilson and William Lee, also served in the Canadian military – Wilson with the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War and William in the Korean War.

During her time in the RCAF, Jean was invited to meet Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King in 1943, and was in the Guard of Honour for China’s then first lady, Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, during her visit to Canada in June, 1943.

Jean and two fellow Chinese-Canadian Second World War veterans, Corporal Lila Wong and Private Marion Laura Mah, were among the first Chinese-Canadians to receive their Canadian citizenship certificates under the Canadian Citizenship Act of 1946, which created the new category of Canadian citizenship. Prior to that, Canadians were British subjects. In his speech to the recipients, Chief Justice Farris said, “You have earned your right to a citizenship by the part you played in the armed forces of the World War just over”.

Jean turned 98 years old on October 11, 2021.

Worked in the Dominion Bureau of Statistics in Ottawa to support the war effort.

During the Second World War, Kay Livingstone moved to Ottawa to work as a secretary in the Dominion Bureau of Statistics, supporting the war effort. She married George Livingstone, a corporal in the Canadian Army, during the war. She moved to Toronto after the war where she had a career in radio and the performing arts.

She was a prominent member of the Toronto Black community, founding the Canadian Negro Women’s Association in 1951 . It was dedicated to community service including providing wheelchairs for injured Black soldiers.

Kay served as the first president of the Canadian Negro Women’s Association from 1951 -1953 and organized the first National Black Women’s Congress in 1973.

Served as dispatch carrier with the 107th Pioneer Battalion in France

Tom was a champion long-distance runner who lived and trained in Toronto during his athletic career. He was a very accomplished athlete, winning the Boston Marathon in 1907, Toronto Ward’s Island Marathon from 190 6-09, and the 1909 World Professional Marathon Championships, in New York City.

On February 17th, 1916, at the age of 29, Longboat enlisted in the Armed Forces. He served as a dispatch carrier with the 107th Pioneer Battalion, where he ran messages and orders between units. He continued to run competitively while in the Army. In 1918, he won the eight-mile race at the Canadian Corps Dominion Day competitions .

He was injured while in service, but survived the war and returned to Canada in 1919. After returning to Canada, he lived and worked in Toronto until eventually retiring to his home community of Six Nations where he died in 1949.

Born on April 2, 1916, in Toronto, Donald Arthur MacLean grew up in a lively household with his parents, James and Edith, and three siblings.

When the Second World War began, MacLean’s sense of duty led him to the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). After training as a navigator, he was sent to England and joined 97 Squadron in late 1942. Over the next few months, he flew on seventeen missions.

The Dam Busters Raid was conducted by the RCAF on May 16-17, 1943, aimed at destroying German dams in the Ruhr Valley. The mission involved using specially designed “bouncing bombs” to disrupt industrial production and flood the area. MacLean’s navigation log told a compelling story of their daring mission. At 12:20 AM, just before they reached their target, he jotted down, “W.Op fixing TR9 under my table.” By 12:30 AM, they had arrived at the target and by 12:46 AM, the bombs were released. However, their path took an unexpected turn over the heavily defended town of Hamm, Germany. Despite this, McCarthy skillfully maneuvered them back on course without incident.

For their courage during the raid, MacLean and the pilot were both awarded Distinguished Flying Medals (DFM). Although MacLean had recently been commissioned and was technically eligible for the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), he chose to decline the upgrade, preferring to keep the DFM he had earned.

After the war, MacLean continued his service with the RCAF, retiring as a Wing Commander in 1967. His post-war years included a role as Director of the Ontario Health Insurance Program (OHIP) in Toronto. He married Josie, a former wireless operator, in 1944, and together they raised four children. MacLean’s career took him across Canada, the U.S.A, and even London, U.K. before he finally retired in 1981. He passed away in Toronto on July 16, 1992.

Served in the 18th Battalion from Western Ontario, in France during the First World War and in the Veterans Guard of Canada in Toronto during the Second World War.

Mathew Solomon Mandawoub was born on the Saugeen First Nation on October 26, 1896. On March 28, 1918, he joined the 18th Battalion from Western Ontario and served in France. On August 1918, Mathew’s Battalion was part of the 100 Days Offensive, the push to move the Germans out of France and end the war. During battle, he was shot above the elbow on his left arm. He was taken to a General Hospital near the English Channel and had surgery to remove the bullet. He remained in hospital until November 29 and was discharged on January 13, 1919, in London, Ontario.

Mathew returned to the Saugeen First Nation and married Laura James. They raised a family of nine children. In 1940, Mathew joined the Veterans Guard of Canada made up of First World War veterans who supported the war effort on the home front. Mathew was assigned to guard a Prisoner of War camp in Mimico.

Mathew did not report for one of his shifts and was identified as “absent without leave”. Five days later, the body of a soldier was found in the Keating Cut, off Villiers St. near Cherry Beach, in Toronto. The commanding officer identified the body as belonging to Mathew Solomon, aged 45.

He was awarded a military cross and his personal effects were sent to his wife. His remains were delivered to Southampton and he was buried in the Saugeen Village Cemetery.

From a story researched and written by G. William Streeter

Corporal, Signals Operator, 2 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group (CMBG)

Died: May 25, 2007, age 25

Matthew was born in Toronto and grew up in Orangeville attending St. Peter School and later Orangeville District Secondary School. He had a love for the outdoors – winter camping, rock climbing, fishing. He was an avid reader and maintained a high level of physical fitness.

In 2001, Matthew enrolled in the Canadian Forces Primary Reserve as a Supply Technician with the Lorne Scots Regiment. In 2002, he joined the Regular Force as a Signals Operator. He went to the Canadian Forces School of Communications and Electronics for Signal Operator Apprenticeship training which he completed in2003.

Matthew was 1st deployed to Afghanistan in 2003 on Operation Athena. His 2nd tour was in 2007 where he was a member of the Operational Mentoring & Liaison Team where he trained Afghan soldiers. He tragically lost his life when he stepped on an improvised explosive device while on foot patrol near the village of Nalgham, Afghanistan.

Kathleen McGrath was born on Queensway Farm, located close to Toronto. She embarked on a nursing career at age 17 and by 1937, had qualified as an Ontario Laboratory Technician. In 1941, her expertise caught the attention of Dr. Clifford A. Taylor, an ophthalmologist at Christie Street Veterans’ Hospital and Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto. McGrath began focusing on fitting and later manufacturing prosthetic eyes.

Together, they traveled across Canada, providing ocular prosthetics to ex-servicemen. By 1946, their clinic had supplied eight hundred prosthetics to veterans. As she gained experience, McGrath began producing the prosthetics herself. Known as an “eye-maker,” she specialized in both glass and plastic prosthetic eyes. Her dedication kept her in the workforce longer than many women in her time, as the need for ongoing care for rehabilitating service personnel continued after the war. McGrath retired in 1955. She passed away in Ottawa in 2011.

The Christie Street Veterans’ Hospital, opened in 1919 and renamed in 1936, was a key facility for veterans’ care. In the 1940s, Sunnybrook Hospital was built to accommodate overflow, with the first patients transferred in 1946. Christie Street Veterans’ Hospital was later converted into a senior’s home before being demolished in 1981.

Flying Control Operator in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War.

Katherine was completing her General Arts degree at Queens University when she decided instead to enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force at 20 years old. She was offered different positions including photographer, cook or general office clerk and chose to be a Flying Control Operator.

After training in Halifax, Katherine was stationed ‘overseas’ at the Air Force Base in Gander, Newfoundland which at that time, was not part of Canada. Gander was the largest airport in the world during the war and was the closest refueling station to the UK. Cross-oceanic bound planes flew through Gander.

Katherine’s responsibilities were to communicate with pilots in radio range upon their approach and take-off, and assign runways. Planes were sent in fleets so there was constant contact with pilots from the control tower, with planes often landing every two minutes. If there was a crash, Katherine had to call in the emergency trucks, and crashes were frequent. The American pilots in particular had little flying experience and Gander was a tricky location with a down draft from a nearby lake and a hill that trapped air currents at night.

Corporal, 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment

Died: December 5, 2008, age 23

Mark Robert McLaren was born in Toronto and called Omemee, Ontario (near Peterborough), his hometown.

He joined the Canadian Forces in the summer of 2002 as a reservist and member of The Hastings & Prince Edward Regiment before joining the regular force as a member of the 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment.

Mark served two tours in Afghanistan earning the Medal of Military Valour (MMV) for heroic actions in battle. He was injured in the neck and leg by “friendly fire” during his first tour in 2006. During his last tour, he was working as part of a special liaison team training the Afghan National Army.

Sadly, on December 5, 2008, Mark lost his life with two additional Canadian soldiers, after their armoured vehicle hit a roadside bomb during a joint patrol with the Afghan National Army west of Kandahar City.

The Canadian Coast Guard vessel “CCGS Corporal McLaren, MMV” was named in his honour.

Private Stephen Michell & Doreen Cambridge

Stephen Michell and Doreen Cambridge were next door neighbours on Vaughan Road, and their families quickly became fast friends. The Cambridge family moved to England in 1938, but fate would soon bring Stephen and Doreen back together during the Second World War. Stephen enlisted in the Royal Regiment at the start of the war, first training at Fort York, then Iceland and finally arriving in England in 1941. Asked by his uncle who was also a friend, to deliver mail to the Cambridges upon his arrival in England, Stephen and Doreen quickly reconnected with each other. While Stephen prepared for what would be known as the Dieppe Raid, he spent his leave with Doreen who was an active member of the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Corp (CWAC).

Like almost 2,000 of his fellow soldiers, Stephen was taken as a Prisoner of War at the Dieppe Raid. However, he and Doreen continued writing faithfully to each other. During this time, Doreen kept herself busy with the CWACs, rerouting mail to dentists stationed throughout the conflict zones.

Stephen was a member of the camp band, who many years later composed the march “Men of Dieppe” in tribute. Stephen and the band used their music to engage in subversive activities to derail German success. The band even aided in helping 52 men escape, playing loudly to cover up the sound of a tunnel being dug.

Stephen married Doreen in England after he was liberated in 1945. They returned to Toronto and moved to Hastings Avenue before building a home on Havendale Road. Stephen took a job with Canada Post and the couple welcomed four children. In 1958, the family relocated to Huntsville.

Stephen continued to compose music and published two books about his experiences, “They Were Invincible”, published in 1967 and a second, full version, “Profile on Twelve Platoon” published by his son in 2019. He played in the Muskoka District Band well into his golden years.

He played in the Muskoka District Band well into his golden years. He passed away in 1994. Stephen’s march, “Men of Dieppe”, is still played by the Royal Regiment, and other military bands today.

Doreen later becomes Huntsville’s first ever Red Cross Homemaker: a role where women would provide homecare to local families when a parent became ill.

Doreen passed away in 2008 and her husband passed away in 1994. Stephen’s march, “Men of Dieppe”, is still played by the Royal Regiment, and other military bands today.

Following Stephen’s death, his son was was digging through his stack of hand written manuscripts, when he came across an untitled poem written in his father’s hand.

What has happened to the world we once knew?

The world that vibrated with the Warmth of human friendship.

A love of simple things; an old beat-up jalopy, a guitar, the twinkling lights of small towns passed in the moonlight.

In those not-so-far distant days we laughed… loved… and danced to the throbbing beat of drums and keening note of saxophones and strident brass.

With full hearts and empty pockets, we toasted Eros… and were gay.

Then came the call: the bugles blew, and like the fools of every generation, we responded to the sound; aware, as all the world was well aware, a monster had arisen, and must be speedily dispatched… demolished… and interred.

The follies of the fathers must be passed down to the sons, as it has ever been since time in memorial, and therefore we must answer for the folly of Versailles.

In our blood and in the blood of millions upon millions far away, the debt must be repaid.

And as we went… millions of marching feet; each of us wearing bandoliers filled with tiny messengers of death, small, lethal hornets that hum and kill; dispatched from tubes of steel, each one intended for the heart of a brother, far away.

When Cain slew Abel, he was condemned by his kind; Outcast… adrift, a creature to be avoided and abhorred; while we, the product of a higher degree of culture, were dispatched with, love and kisses from our kin, and the blessings, and the prayers of the clergy.

It just shows how much we have advanced in a few thousand years.

Three thousand miles away, our brothers waited for us to arrive so that they could match their powers of annihilation with ours.

There was nothing personal about it; it was just that they were under orders, as were we.

The lies we both were told, were superfluous, just fodder for our consciences. On no account must we be allowed to bear the guilt of having violated the commandment:

Thou shalt not kill; thou shalt not…

Private Arthur William Montgomery, Royal Regiment of Canada, died August 19, 1942, at age 23.

Private Ralph Eric Montgomery, Royal Regiment of Canada, died August 21, 1942, at age 23.

Twin brothers Arthur and Ralph Montgomery joined the Royal Regiment of Canada on the same day in 1940. They trained together, fought together at Dieppe and ultimately died together at the age of 23. Ralph was injured and succumbed to his wounds on August 21, 1942, while Arthur was reported missing after the raid but later confirmed to have been Killed in Action on August 19. Growing up in the Gerrard and Greenwood area of Toronto, the twins’ lifelong friend Private Russell Roderick Brown also enlisted with them in 1940 and died at Dieppe on August 19.

In 1941, when they first went overseas, the twins wrote their mother a letter saying, “if anything should happen to us, keep your chin up, Mom.” Mrs. Montgomery remained a steadfast supporter of war bonds even after the death of her sons. The Montgomery twins left behind their parents, Mr. and Mrs. C.W. Montgomery, as well as their brothers, Corporal Roy Montgomery and Leading Aircraftman, Wilfred Montgomery who were also fighting in the war.

Marion Alice Orr, CM: Second Officer, British Air Transport Auxiliary

Marion Alice Orr was a pioneering Canadian pilot who, along with Violet Milstead, was one of only four Canadian women to serve in the British Air Transport Auxiliary, a civilian organization established during the Second World War ferrying aircraft and equipment between military sites.

Marion was inspired by watching aircraft at Barker Field in Toronto in her youth (present day Yorkdale). Over time, she saved up enough money to take flying lessons where she met Violet Milstead and the two spent many hours flying together. In 1940, she earned her private pilot’s license and worked as an aircraft inspector at De Havilland Aircraft of Canada. She received her commercial pilot’s license in 1942 and became the second Canadian woman to qualify as an air traffic control assistant.

In 1943, she travelled to Britain with Violet to work in the Air Transport Auxiliary where she earned the rank of Second Officer. After leaving the Auxiliary in 1944, she returned to Toronto where she became a flight instructor. She became the first woman in Canada to own and operate a flying school after purchasing Aero Activities Ltd. and developing her own airfield.

Marion was inducted into the Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame in 1982. In 1993, she was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada. She died in 1995 at the age of 76.

The City of Toronto has partnered with Heritage Toronto to create a plaque, which will be installed at 2360 Yonge Street, in commemoration of Marion Orr’s service and contributions of to the war effort.

Rahim grew up in Afghanistan, during a time where learning English was not highly valued. However, he displayed a keen interest and pursued learning this second language. In 2008, his excellent verbal proficiency led him to an interpreter position with the NATO International Security Assistance Force.

Between 2008 and 2010, he was assigned to the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) to support communication between Canadian mentors, the Afghan National Army and the Afghan National Police in Kandahar.

Positioned in a volatile area, Rahim’s daily responsibilities involved accompanying the contingent on missions to patrol and clear Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) to ensured the safety of local residents as well as military personnel. These operations frequently encountered severe crossfire, placing lives in constant jeopardy.

Rahim deeply admired CAF personnel and their respectful and compassionate treatment of the Afghan people in various sensitive situations. Because of this, he made a personal pledge to the CAF and to his country to be present and provide assistance.

In 2011, Rahim transitioned to the Joint Regional Afghan National Police Center, where he worked alongside American forces. Following that, Rahim immigrated to Canada with his wife and son. He maintains a strong bond with his Canadian mentor from his time in Afghanistan and expresses immense gratitude to the Canadian Government for assisting him and his family in safely repatriating to Canada. Today, Rahim is a devoted husband and proud father of two sons.

Albert Randall was born in Toronto on September 9, 1920. At age 20, he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Reflecting his humble nature, he once explained, “I just wanted to help out and do my little bit for the war effort.” Trained as an air gunner at No. 1 Bombing and Gunnery School in Jarvis, Ontario, Randall was commissioned as a pilot officer in September 1942. He was assigned to 419 “Moose” Squadron, Canadian 6 Group, part of RAF Bomber Command, stationed in Middleton St. George, Durham, England.

During his 16th mission over Germany on May 13, 1943, his Halifax bomber was shot down over Duisburg. Two of his crew members did not survive. Randall was captured and taken to Stalag Luft III, the infamous prison camp known for the Great Escape. He endured two forced marches across Germany in the final months of the war. Reflecting on his experience later in life, he remarked, “Being a prisoner of war was unfortunate, but I was a survivor. Would I do it again? Why sure I would, yeah, if I was 21, yeah, sure I would.”

After the war, Albert went on to have a successful career at Loblaws, where he met his future wife, Mary, in 1946. They were soon married and raised four daughters, two dogs, and several other pets. For his dedicated service to veterans and their families, he was awarded the Sovereign’s Medal for Volunteers on November 14, 2002. As chair of the Toronto RCAF POW Association, he organized events and supported ill members. He also volunteered at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, assisting veteran patients and educating youth about Canada’s wartime contributions, preserving the legacy of veterans.

Albert was cherished by all who knew him. In his later years, he moved to Sunnybrook Veterans, where he continued his lifelong commitment to serving others, supporting his fellow veterans for over 25 years. His dedication and kindness left a lasting impact on his community and will be remembered by many.

Eva May Roy, born in Toronto, Ontario, worked as a presser in a laundry service and after the outbreak of the Second World War as a machine operator and fuse assembler at a munitions plant in Ontario.

In 1944, she enlisted with the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC), where she trained as a cook and served in military canteens in Canada, the UK, and the Netherlands. Her deployment overseas was rare; only one in nine Canadian women in the army served abroad during the war.

Roy became the subject of one of Canadian artist Molly Lamb Bobak’s most famous paintings, titled “Private Roy.” While the painting, which depicts Roy at a military canteen in Halifax, captures a stern appearance, Roy was known to be a warm, compassionate, and lively individual with a love for singing.

After returning to Canada in January 1946, Roy worked as a government postal clerk in Toronto. A decade later, she re-enlisted with the CWAC, serving from 1955 to 1965 and was promoted to the rank of sergeant. Throughout her service, Roy was part of a vital group of women supporting the war effort, as one of approximately 50,000 women serving in various roles during the Second World War.

Private, 3rd Battalion Group, Royal Canadian Regiment Fallen: July 15, 1953. Buried in the United Nations Cemetery in Busan, South Korea

Billy Regan came from a family of seven children. As the only son, his father was not supportive when Billy enlisted in the Royal Canadian Regiment in 1950 at the age of 16 given he himself had just returned home after the Second World War –. His first deployment was as part of the United Nations multinational force in Korea. Like many of his comrades, he wasn’t even old enough to vote or drink legally.

During the Battle of Hill 187, the 3rd Battalion Group of the Royal Canadian Regiment had to hold their position on the hill while faced with three waves of attacks. Their position was held but at a cost of 26 Canadians deaths, 27 wounded and seven taken prisoner. Billy was wounded by enemy mortar fire and evacuated by helicopter to a MASH unit where he died of his wounds on July 15, 1953. At the time of his death, ten days before the armistice took hold, he was just 19 years old. He was one of the last Canadians to be killed during the Korean War.

Buried in the United Nations Cemetery in Busan, South Korea, a symbolic brick in honour of Billy is found on the Korean Veteran Association of Canada’s Wall of Remembrance, in Meadowvale Cemetery in Brampton.

Pilot Officer, Royal Canadian Air Force

Died: July 15, 1944, age 30

Warrant Officer Class II (Navigator), 458 (Royal Australian Air Force) Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force

Died: June 16, 1943, age 31

The Scandiffio Brothers were born in Toronto. Assigned to separate roles and squadrons, they occasionally saw each other in the spring of 1942, in England before going their separate ways. Thomas mentioned in a letter home, that the brothers had seen every continent together except South America.

Both brothers were avid letter writers and enjoyed the packages and treats from home.

Thomas (Tom) attended St. Michael’s College at the University of Toronto and Osgoode Hall. He enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force upon his graduation from law school. He was called to the Bar before going overseas.

He failed to return from operations while flying a mission in a Wellington aircraft in the skies around Malta. He was listed missing in action, and was never found. His name is inscribed on the Alamein War Memorial in Egypt.

Francis (Frank) enlisted in March 1941, and trained in Canada to receive his pilots’ wings. In 1944, while in the Pacific, he failed to reach his destination on a transfer flight. After encountering bad weather, his plane crashed on a mountain top. He is buried in the War Cemetery in Delhi, India.

In of his last letters home written to his sister Millie, Francis mentioned that he had a pretty good baseball team consisting of Canadians, a New Zealander and two Australians. His team was planning to carry out the challenge to play an American team from the U.S. Army Air Corps.

Both brothers died a year apart and in their 31st year. They never married and were survived by their mother, two brothers and three sisters. Their mother received the news of Francis’ death while Thomas was still listed as missing.

Thomas Scandiffio’s record can be found in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and the Database of Fallen Aviators

. The Canadian Letters & Images Project has also profiled him: Thomas Peter Scandiffio

.

Francis Scandiffio’s war record is also listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and Database of Fallen Aviators

He is featured in the Canadian Letters & Images Project: Francis Michael Scandiffio

Sergeant, No. 22 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force

Died: April 6, 1941 at age 20

James Scott was a prominent athlete who played hockey, football and basketball and also rowed for the Argonauts Rowing Club. He volunteered in the Royal Canadian Air Force, while still a student at the Northern Vocational School in Toronto.

He had two brothers, who were both in the service, one in the RCAF in England and the other in the Engineers Corps of Canadian Officers Training Corps. He also had a sister.

While serving in France, James was a navigator in a Beaufort bomber. His torpedo bomber was downed while on a “suicide attack” attacking enemy ships in the harbour at Brest, France.

Torpedo bombing required both skill and nerves of steel. The flight path of the crew had to skim across the water, facing point-blank fire from anti-aircraft guns. The torpedo they launched caused significant damage to the hull of the ship, before his aircraft crashed into the cruiser’s deck.

Back home, his mother received the cable that her son was missing in action. This news added to her grief as she recovered from the death of her father in Canada.

James Scott is listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial which includes media articles about his service. More information can also be found in these articles: Dropping ‘Fish’: Air Force, Part 44

, and Database of Fallen Aviators,

Royal Canadian Air Force Association.

Verda Sharp was born in Toronto in 1917, married early in life and had two children. When her marriage ended in the mid-1930s, leaving her as a single mother during a challenging economic period, Sharp returned to her parents’ home, and undertook work as a clerk and switchboard operator at a private medical clinic in Toronto.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, she seized the opportunity for stable employment and joined the workforce at the Dominion Bridge plant in Toronto. Initially, Verda worked on a riveting team, where she fastened together metal pieces. This demanding job required precision and care, as the red-hot rivets posed a serious risk of burns. As the war escalated, Dominion Bridge expanded its production to include munitions, and Verda was transferred to the department making cartridge cases for anti-aircraft shells.

After the war, Verda married Sanford Cook and left her factory job to focus on raising her family. However, she continued to build a career, attending secretarial school, and later securing a position at the YMCA. Over the next 31 years, Verda rose through the ranks, achieving prominent roles within the organization.

Beyond her professional success, Verda became a respected community leader in Toronto. She was instrumental in founding the Congress of Black Women and the National Black Coalition, advocating for social justice and empowerment for Black Canadians. In recognition of her extensive contributions to her community, Verda was awarded the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Medal in 1977, a testament to her resilience, leadership, and enduring commitment to community service.

Served as Private in the 20th Canadian Infantry Battalion in France

Died: 1919 in Kitchener, Ontario at age 25.

Buckam Singh immigrated to British Columbia in 1907 at the age of 14, eventually moving to Toronto in 1912. During this time, South Asian immigrants faced many barriers including a requirement that all immigration to Canada was to occur through a continuous journey from their country of origin.

This was at a time when there were no direct ships from India to Canada. In addition, Sikh men were not allowed to immigrate with their families.

Despite these challenges, Singh enlisted to fight in the First World War in 1915 at age 22, in the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force. He became the first Sikh man to enlist in the Canadian Army during the First World War. He was posted in France and served with 20th Canadian Infantry Battalion in Flanders. Singh was wounded twice in separate battles. While recovering in England, he contracted tuberculosis and was sent to Canada to recover.

He spent his final days in a Kitchener, Ontario military hospital, dying in 1919 at age 25. His burial place is the only known WWI Sikh Canadian soldier’s military grave in Canada.

Lieutenant, Royal Canadian Infantry Corps, serving with the British Royal Scots as a CANLOAN Officer

Died: September 15, 1944, age 30

Jackson Stewart studied at the University of Toronto, becoming a teacher and principal in Cheeseville and Thistletown.

He enlisted as a Private in July 1942, was promoted to Corporal and was commissioned as an officer on December 22, 1942, on the date of his marriage to Marjorie Grace.

Lieutenant Stewart was part of CANLOAN, a British army plan to recruit Canadian volunteers for service in the British army. The plan secured 673 volunteers in 63 regiments. The CANLOANs performed superbly in action, and their regiments grew to appreciate Canadian informality and sense of adventure.

He was wounded in July 1944, but rejoined his regiment and sadly died that September. Lieutenant Stewart was one of 128 Canadian service people killed in action while serving with the British Army.

Two of his six brothers also served. He was survived by his wife Marjorie Grace, whom he had married just two years before his death, as well as a sister. He was buried in Kasterlee War Cemetery in Belgium.

Lieutenant Stewart’s record is listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial .

Rank: Lance Sergeant, 15 Canadian General Hospital, Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps

Date of death: October 18, 1942, age 45

Rank: Lance Corporal, Royal Hamilton Light Infantry

Date of Death: July 25, 1944, age of 27

Rank: Gunner, Royal Canadian Artillery, 2 Anti-Tank Regiment

Date of Death: July 21, 1944, age 22

David Dudley and Mary Lillian Stewart had four daughters: Lillian, Mabel, Gertrude and Helen, and two sons, David Henry and George Edwin. Tragically, father and sons all died during the Second World War. David Sr. died in England in 1942, and both brothers perished in Normandy, within five days of each other. All three of them are buried overseas in England and France.

David Dudley was single and a clerk at Eaton’s, when he enlisted in the First World War at age 20 in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). After arriving in England in April 1917, his chronic bronchitis led to lung tuberculosis. He was repatriated to Canada in November for medical treatment.

He then enlisted in 1939 during the Second World War. He served in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps that was responsible for all medical and dental services in the Army. The Corps delivered the wounded to battlefield medical stations (Casualty Clearing Stations), or to hospitals for more intensive medical care.

David would be joined a few years later by his two sons, David Henry and George Edwin who then left behind their mother and sisters in Toronto.

David Henry enlisted in March 1942 at age 26 in the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry as a Lance Corporal. His brother George Edwin would enlist six months later in September 1942, at age 20, as a Gunner in the Royal Canadian Artillery.

Sadly, a month after George Edwin enlisted, his father David Dudley, died in Bramshott, England in October 1942. He is buried in Brookwood Military Cemetery, Surrey, England, the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the United Kingdom.

On June 6, 1944, the invasion of Normandy, now known as D-Day, began when Allied forces invaded the mainland of Northwest Europe. It was a formidable task as the Germans had turned the coastline into a continuous fortress. While the invasion was a magnificent accomplishment, more fighting lay ahead as victory in Europe was still 11 months away. The Normandy Campaign, which saw almost 5,000 Canadian soldiers perish, lasted until late August 1944.

Both Stewart brothers perished five days apart in the Normandy campaign: George Edwin died at age 22 on July 21, 1944, followed by his brother David Henry who died at age 27 on July 25, 1944. David Henry is buried in Bretteville-Sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery in Calvados, France among the almost 3,000 casualties. His brother, George, is memorialized at the Bayeux Memorial also in Calvados, erected in honour of more than 1,800 who died with no known graves.

Mary Lillian lost both her husband and her sons, and four girls lost their father and brothers. The sacrifice of this family can never be forgotten.

David Dudley is listed in the Personnel Records of the First World War and the Canadian Virtual War Memorial

. His story is also in the Official History of the Canadian Medical Services, 1939-1945

.

The brothers are both listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial (David Henry) and Canadian Virtual War Memorial

(George Edwin).

Mary Ann was born in York Township in 1842 and by age ten, was already listed in the 1851/52 census as a farm servant.

She married at 19 years old, spending the next forty years with her husband as tenants on a 100-acre farm near Humber Summit, North Toronto. Their children grew up and stayed in Toronto, but the couple’s life remained tied to the land.

Beyond her roles as wife and mother, Mary Ann was deeply passionate about poetry. In Toronto’s literary circles, she gained recognition for her poignant recitations, often accompanied by a magic lantern that projected images from glass slides, creating an immersive experience.

During the First World War, Mary Ann used her creative talents to support the war effort, creating slides and poems for war-related presentations. Notably, her poem Over the Top or The Taking of Vimy Ridge by the Canadians was described as an “official report in rhyme.” Her poetry, filled with patriotic fervor, served as home-grown propaganda that bolstered public support for the Allies.

Mary Ann Sutton passed away in January 1920, but her legacy endures through her poetry and slides preserved in the Canadian War Museum. Her work provides future generations with a glimpse into how art and patriotism intertwined during a pivotal historical moment.

Over the Top; or, The Taking of Vimy Ridge by the Canadians (1917), by Mary Ann Sutton

Lieutenant, The Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery

DIED: April 22, 2006, age 40

Lt. William (Bill) M. Turner, a former teacher and mail carrier for Canada Post, served with The Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery. Born in Toronto, he grew up in Elmvale, a town located an hour’s drive north of Toronto.

In 1982, Lt. Turner graduated from Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario with a Science degree. He remained in Ontario, working at the University of Guelph as a research assistant while pursuing a degree in education, focusing on biology and physical education.

In 1991, Lt. Turner enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces reserves, joining the 11th Field Regiment. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1993 and transferred to the Edmonton-based 20th Field Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery, a Primary Reserve field artillery unit, in 1996. During this time in Edmonton, he also worked as a mail carrier for Canada Post.

In March 2006, Lt. Turner was posted to Afghanistan, where he served as a Civilian-Military Co-operation officer. In this role, he worked as a liaison between the Canadian Forces and village elders and leaders.

On April 22, 2006, Lt. Turner was one of four Canadian soldiers killed when their light-armoured G-Wagon vehicle was blown onto its side by a roadside bomb near Gumbad, approximately 75 kilometres north of Kandahar, Afghanistan

Violent Milstead Warren, CM: First Officer, British Air Transport Auxiliary

Toronto-born Violent Milstead Warren was one of the first Canadian female bush pilots. She also served overseas as one of only four Canadian women in the British Air Transport Auxiliary.

She worked in her mother’s shop to save enough money to take flying lessons. In 1939, Violet received both her private and commercial aviation license . After receiving her instructor’s certification in 1941, she trained military personnel and taught flying lessons to private citizens at Barker Field in Toronto (present day Yorkdale). In 1943, while travelling with her fellow pilot, Marion Orr, Violet joined the British Air Transport Auxiliary: a civilian organization established during the Second World War. She earned the rank of First Officer and transported equipment between factories and military sites.

Violet demonstrated a high level of intuition and skill while flying eight times per day over two week stretches during her service. She piloted nearly 50 different types of aircraft. She flew mostly on instinct using maps and compasses to guide her as radio communication was not allowed by Air Transport Auxiliary pilots for fear of being intercepted. Despite doing comparable work, she was paid at a rate that was 20 percent less than male pilots.

In 1945, Violet was discharged from the Air Transport Auxiliary and returned to Barker Field as a flight instructor, later moving to Sudbury. She was the longest serving female Canadian pilot with the Air Transport Auxiliary. She was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada in 2004 and received the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2012 among many other honours. She passed away in 2014 at the age of 94.

The City of Toronto has partnered with Heritage Toronto to create a plaque, which will be installed at 2360 Yonge Street, in commemoration of the contributions and trailblazing life of Violet Milstead.

Section Office, 116 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force

(Women’s Division)

Died: November 8, 1943 at age 24

Irene was born in England and lived in New Toronto with her family for 19 years, attending New Toronto Public School and Mimico High School. In addition to her parents, she had two sisters and two brothers. One of her siblings Sgt.-Maj. David Watson, was part of the Tank Corps.

Irene was a Globe and Mail correspondent and a stenographer-reporter for The New Toronto (South Etobicoke) Advertiser, Ontario’s largest weekly newspaper.

She enlisted in February 1942 and requested to work in an administrative role.

She was serving in Newfoundland as part of #116 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron, when the Canso aircraft that she and 11 others were flying in attempted to land in bad weather and poor visibility. Tragically, they crashed nose-first on a lake in Newfoundland. Only five aboard survived.

Section Officer Watson was believed to one of the first airwomen in Canada to be reported missing and also killed in active service. Sadly, she was declared dead and her body was never recovered. Her name is inscribed on the Ottawa Memorial commemorating members of the Air Forces of the British Commonwealth who lost their lives.

She is also one of only five women who are listed in Toronto’s Golden Book of Remembrance.

Irene Watson is listed in the Canadian Virtual War Memorial and the Database of Fallen Aviators

.

Lieutenant William George Rogers Wedd lived in the Bedford Park area and was a member of the Royal Regiment of Canada. He landed with his platoon at Blue Beach in the first wave. Under heavy fire, he was able to bring his platoon to the sea wall and then realized only about 10 of his men had survived thus far. A pill box on top of the sea wall was sending heavy fire towards Wedd’s platoon. Seeing no other way, Wedd instructed the laying of a Bangalore torpedo, blowing a hole in the barbed wire on top of the sea wall. Wedd then led his platoon through the gap toward a direct assault on the pill box.