Fine Art & Artifact Collection

Toronto History Museums Fine Art and Artifact Collection features over one million archaeological specimens,150,000 artifacts and 3,000 works of art that reflect the 11,000-year span of human occupation in the Toronto region.

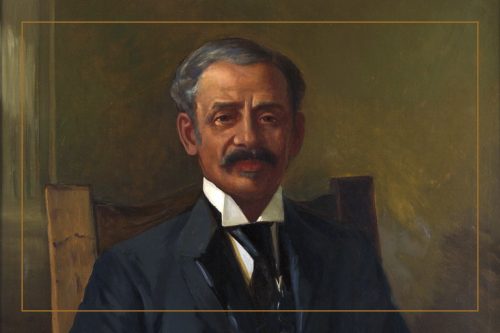

William Hubbard was the son of refugees escaping slavery in the U.S. who came to Toronto in 1840 via the Underground Railroad. Payton was born in Toronto in 1842 and became a professional baker specializing in cakes. He also worked as a driver and drove for journalist and politician George Brown before running for political office himself at the age of 52. He was elected as Alderman in 1894, the first Black elected official in Toronto history, and his political career included membership on the City’s powerful Board of Control, as well as serving as Acting Mayor when the Mayor was unavailable.

He was known for his public speaking abilities at City Council and was given the nickname “Cicero” after the Roman orator, in honour of his talents with language. Although he rarely spoke about racism and discrimination, his successful political career was not free from challenges. When Hubbard went on a business trip to Washington D.C. in 1907, it was necessary for him to carry a letter from the Mayor Emerson Coatsworth of Toronto as a character reference. Hubbard was a fervent supporter of public utilities and championed the creation of High Park by the City of Toronto. This portrait, painted in 1913, was commissioned by a group of his supporters. The portrait was presented to the City in 1914 and was hung in the corridors at Old City Hall.

This one-piece school desk was typical of those found in school rooms across Toronto during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The desktop is hinged and lifts up to reveal storage space below for school supplies like a small slate and slate pencil, or for older students, a quill pen and bottle of ink. All school supplies, including textbooks, would have been the responsibility of the parents or guardians of each student. Each seat was attached to the desk behind and folded up to make moving between the rows of desks easier. The design of these desks required that they be lined up in neat rows and the cast iron legs bolted to strips of wood on the floor. The result was a rigid arrangement of desks lined up in perfect symmetry. This inflexible and disciplined classroom setup mirrored the approach to education more broadly at the time.

Although the idea of crafting a wreath of human hair may sound unusual to us today, the practice of memorializing loved ones in this manner was very common in Victorian times. People would collect the hair left behind in their hairbrushes and would store it in small covered containers called a hair receiver, which usually sat on a dresser or vanity for this specific purpose.

Once sufficient quantities of hair were gathered, they would be carefully combed out and tied in small bundles, to be used in such artwork later on. Incredible artistry, talent and patience were required to fashion these loose bits of hair onto a wire foundation and create remarkable wreaths depicting stylized flowers and foliage. Beads, wire, feathers, seeds or even shells were often incorporated into these fantastic pieces.

This wooden stroller is a playful piece of folk-art from the Scarborough Museum Collection. This functional design from the early 20th century draws inspiration from adult-size horse-drawn carriages typical of the period. It was likely made in a small workshop, perhaps even a carriage works where full-size vehicles were made. Like many objects that cater to children, the stroller models the posture and style of horse-drawn transportation and anticipates the independence of adulthood.