In 1918, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the armistice between the allies and Germany was signed, bringing to an end over four years of war. Almost 70 million young men on all sides had been mobilized. Between eight and 10 million of them were killed or missing, and 20 to 23 million more were wounded.

But this was not just a war fought between armies, this was a war fought between populations: “Total War.” The full resources of the economy and society − manufacturing, transport, personnel, food production, information − were aimed at supporting the war effort. By some estimates, total wartime spending exceeded US$200 billion (approximately US$5 trillion today).

The line between military and civilian blurred, with over 20 million civilian fatalities. Some were victims of military action, many were victims of crimes against humanity, and millions succumbed to hunger or disease. A further 50 to 100 million perished during the ‘Spanish flu’ pandemic, an indirect consequence of the malnutrition, poor hygiene or poor hospital conditions brought about because of the war.

Millions became refugees, either displaced by the fighting or by government policies, forcing people from their homes by being the wrong race or nationality in the wrong place. Empires crumbled, governments were bankrupted and lives were obliterated. But on November 11th 1918, these thoughts were not on people’s minds. The fighting had stopped, the war was over, and the allies had won.

The armistice was signed early enough for the news to reach Toronto by the small hours of the morning of November 11. The Mail and Empire reported that a man who lived on Parliament Street awoke at 4 a.m. to news of the peace, and at once went into the street to tell the news to his neighbours, dressed only in his pyjamas: “Women appeared in the flimsiest of clothing, some covered only with a wrap or kimono, and forgot the cold in the heat of their enthusiasm.”

The Mail and Empire reported “Flags of the victorious nations flew from every home, while cars decorated in flags congested the streets”…”main thoroughfares were a seething mass of humanity, a riot of colour, littered and carpeted with confetti, talcum powder, scraps of paper, and wreckage of every known form of carnival paraphernalia.”

“Yonge Street…during the height of the celebration was almost impassable, so thick were the crowds of joy-seekers.”

According to The Mail and Empire, the news of the armistice was “an assurance Toronto would know no work for the next twenty-four hours.” Streetcar men refused to work, with the extra traffic adding further to the “chaos of confusion.”

Long before news of the armistice reached Toronto, organizers had been planning a Victory Loan parade for that day. Added to the armistice festivities was a martial show of soldiers and tanks, plus an air show by the Royal Air Force. The celebration continued long into the night.

The armistice almost immediately became the focus for commemorations of the First World War by the victorious powers. November 11th is commemorated not only in Canada, but in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and many other Commonwealth countries. It is known as Veteran’s Day in the United States and is also a day of remembrance in France and Belgium.

The First World War was a completely new experience for Canadians, affecting the nation on a greater and deeper level than any previous conflict. Earlier wars were fought by smaller units, made up of professional soldiers or members of the militia, but this was the first war in the country’s history fought by mass civilian armies. Few Canadians did not know a casualty of the fighting.

Perhaps because of this very personal connection, villages, towns and cities constructed memorials to their dead and unknown soldiers, rather than monuments to generals and admirals.

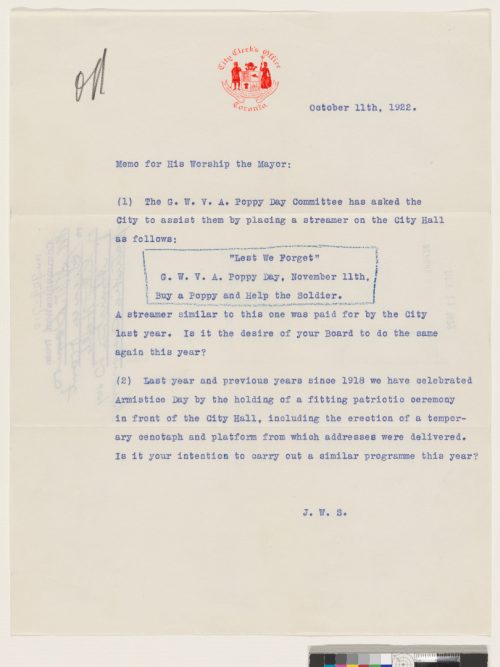

Memorials were placed outside town halls, and in parks, schools, libraries, churches and other public spaces. Private organizations and businesses erected memorials to employees and members who had died. Every year on the anniversary of Armistice Day, survivors, families, the public, and their leaders gathered to remember those who had lost their lives.

In 1931 Armistice Day was renamed Remembrance Day in Canada. Today we remember not only of the fallen of the First World War, but all of the men and women who have sacrificed their lives for their country during times of war, conflict, and peace.

The Cenotaph (from the Greek “kenos,” meaning “empty”, and “taphos” meaning “tomb”), in front of Old City Hall was constructed as Toronto’s official memorial, replacing a temporary wooden structure. The cornerstone was laid on July 24, 1925 by Field Marshal Earl Haig.

The Cenotaph was unveiled on November 11, 1925, by the Governor General, Lord Byng. Byng was commander of the Canadian Corps during the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

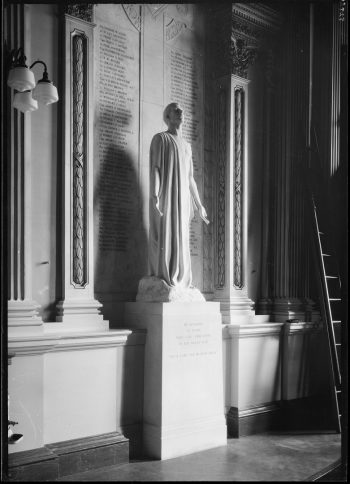

Situated in the Great Library of Osgoode Hall, the memorial statue was sculpted by Torontonian Frances Loring out of Italian Carrara marble. The memorial bears the names of the Ontario lawyers and law students who lost their lives during the Great War. Approximately six percent of the province’s legal profession died during the war.

The Soldiers’ Tower was built as a memorial to the 628 students, faculty, staff and alumni of the University of Toronto who died in the Great War. Completed in 1924, the tower cost $250,000. The balance of the $400,000 raised by the Alumni Association was used to establish scholarships, and the interest on the original $150,000 surplus is still used today for War Memorial Scholarships and for the maintenance of the Tower.

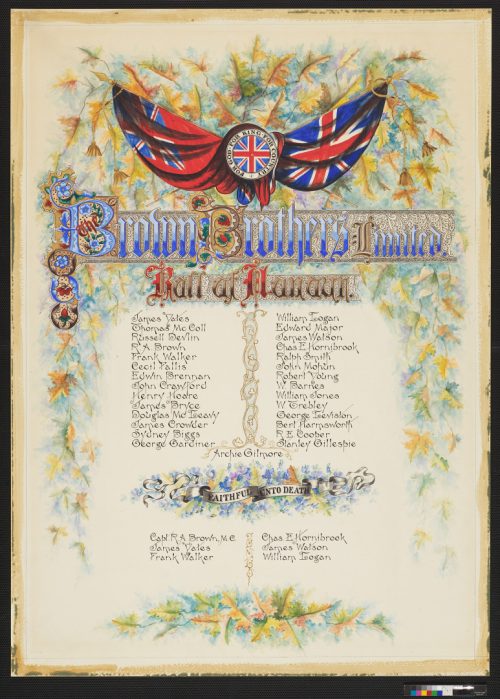

This illuminated manuscript names the Brown Brothers’ employees who enlisted during the First World War and highlights those who never returned. Brown Brothers was a prominent Toronto bookbinder, stationery manufacturer, and dealer in supplies for bookbinders and printers.

The use of the poppy on Remembrance Day was inspired by the first lines of John McCrae’s poem In Flanders Fields. Written in April 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres, McCrae observed how this common European wildflower quickly grew upon the newly-dug-graves of the fallen. The poem was published in Punch magazine that December and quickly became synonymous with the sense of duty and sacrifice of the First World War soldier.

On November 9, 1918, American educator and humanitarian Moina Michael, having read McCrae’s poem, vowed to wear a poppy in remembrance of the fallen. She attended the YMCA annual conference in New York, bringing with her twenty-five silk poppies which she distributed amongst the delegates. Two years later, the National American Legion adopted it as a symbol of remembrance.

In 1920, French YWCA member Anne Guerin attended the American Legion conference with the aim of raising funds for orphans and widows in France. She saw the poppy being worn and was inspired to produce artificial poppies on a large scale in return for donations. She also promoted her idea in Britain and Canada, where the poppy was readily accepted as a memorial symbol by veterans’ associations. Remembrance poppies were worn for the first time in Canada on Armistice Day in 1921.

For the first Poppy Day in 1921, many of the symbolic flowers were made by French and Belgian children. By the next year, responsibility for the manufacture of poppies was passed to Vetcraft Industries. Vetcraft employed disabled war veterans and continued to manufacture the poppies until 1996. Poppies have been distributed by the Royal Canadian Legion, and its predecessors, since 1921.

The poppy endures as a symbol today. Over 20 million poppies are distributed annually in Canada, raising over $16 million for veterans and their families in need.