The first two medical officers of health, Dr. William Canniff and Dr. Charles Sheard, understood that many diseases can be transmitted by bacteria-contaminated water.

By 1900, most of this work was completed, improving living conditions for many people.

In 1907 Dr. Sheard and the City Engineer wrote a report recommending that a water filtration plant be built on Toronto Island.

By 1912 the Island Filtration Plant, located at the west end of Toronto Island, was in operation. The plant filtered water through layers of sand to remove debris. The water was also chlorinated to kill bacteria and other microbes. Cases of waterborne typhoid in the city immediately declined.

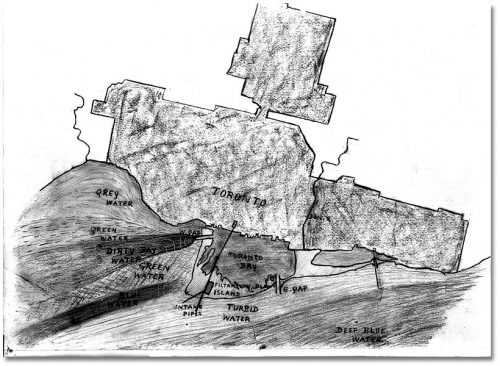

Providing the city with a source of water was one challenge, but there was a larger issue to consider. Sewers emptied directly into Lake Ontario, and Torontonians got their drinking water right from the lake. Since 1896, the department had been testing water quality every week. While the quality of lake water was often acceptable, storms or currents sometimes carried raw sewage from the sewer outfall pipes to the fresh water intake pipe.

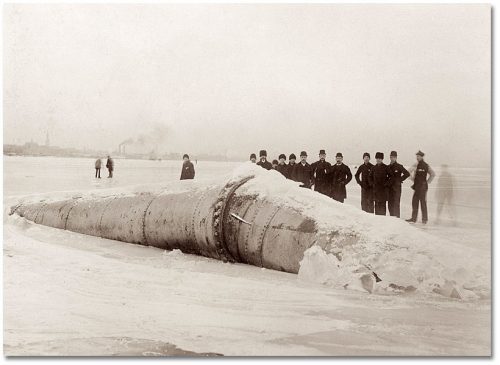

This sketch below shows how the water intake pipe south of Toronto Island was situated in water that could be cloudy, muddy or weedy. In addition, lake currents could carry dirty water from the sewage-contaminated bay to the intake funnel of the water supply pipe.

Water in Toronto Bay was a cesspool of city runoff, industrial pollution and human waste. When the pipe that brought cleaner water from south of Toronto Island through the bay cracked or broke, as it did several times in the 1890s and 1900s, the entire municipal water supply became contaminated. Residents had to boil water, or find an alternate supply for drinking and cooking.

Doctors Canniff and Sheard and the City Engineer all agreed it was imperative to treat both the sewage going into the lake and the water coming out of it.

Because Toronto generally slopes downwards to the south and east, marshy Ashbridge’s Bay in the east end was a logical place for a sewer outlet, and, eventually, a wastewater treatment plant. In 1912 the Ashbridge’s Bay Sewage Treatment Plant was opened.

Soon after the original 1912 sewage treatment plant opened, nearby residents began to complain of the smell. It wasn’t until 1973 that the Ministry of the Environment ordered that the aeration tanks be covered in an attempt to improve the long-standing situation.

Odour control improvements at the plant continue to this day, with the planned construction of a central air collection and treatment system using a biofilter.

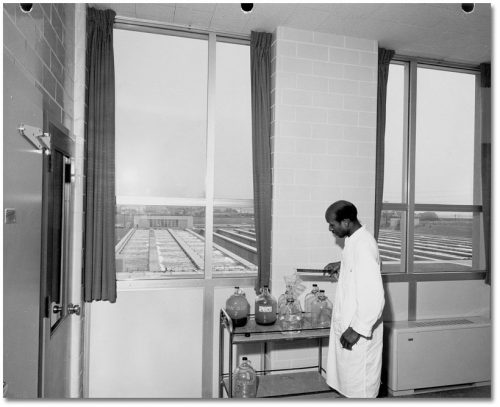

Since 1883, the Department of Public Health has tested Toronto’s drinking water. When the first sewage treatment plant opened, it also tested sewage effluent to ensure the plant was doing its job. The Metro government took over water testing along with the filtration and sewage treatment plants in the 1950s.

Today, the City tests its drinking water several times per day. Quality standards are set by the Ontario Ministry of the Environment.