Dr. William Canniff’s house-to-house inspections revealed all manner of filth in both private yards and public places, and he set out to clean up the city.

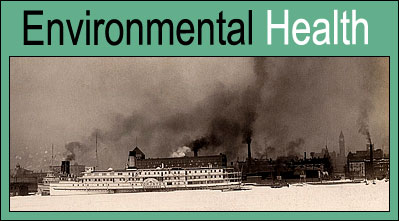

Until 1912, sewer waste drained directly into Lake Ontario, and many found the lake a convenient place to dump any unwanted materials.

Dr. Canniff wrote in 1884 that the area around the docks in Toronto was filled with “all kinds of decomposing organic matter, such as rotten vegetables and fruit, dead animals and fish” and that “anyone who has been along the docks of Toronto during the summer must have noticed by sight and smell that sewage predominates over water.”

While the City government had been picking up garbage since 1834, it was often difficult to know what to do with it.

There were dumpsites, but these filled quickly and the expanding city was running out of places to put more. Refuse was sometimes used to fill in ravines or uneven land, with houses then built on top. The medical officer of health strongly disapproved of the practise as unhealthy.

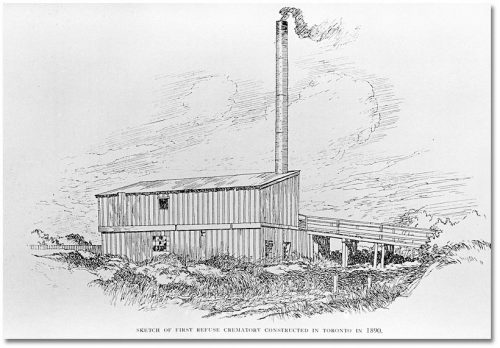

Burning was considered a good method of getting rid of garbage since people believed fire would destroy disease-breeding matter. In 1888, City Council approved Toronto’s first incinerator to burn garbage. It was was built on Eastern Avenue at the Don River, and was completed in 1890.

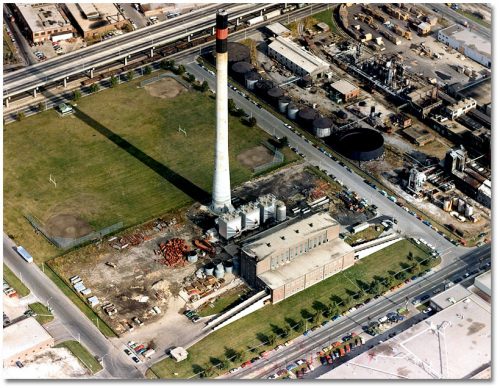

By the 1930s, Toronto had four incinerators in operation. The Commissioners Street incinerator, the last built by the City, was erected in the port area east of Cherry Street. It opened in 1955 with a capacity of 900 Imperial tons per day.

Of course, incinerators produce noxious smoke, and in 1967 when the Metropolitan Toronto government took over responsibility for garbage disposal, it closed most of the incinerators and established large landfills outside of Toronto’s borders.

The Commissioners Street incinerator was closed in 1988, partly due to a Department of Public Health report on its generation of dioxin and other carcinogenic chemicals.

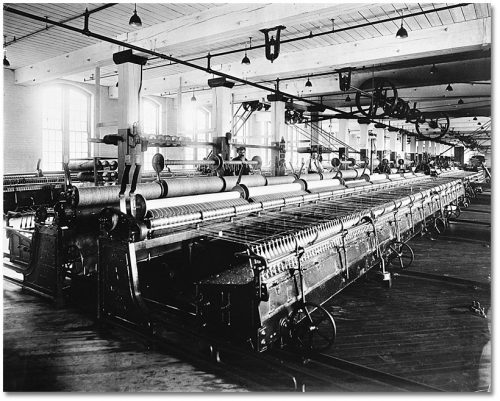

Health in the workplace was also a concern. “The inhalation of injurious dusts, fumes of chemicals, bad ventilation, poor light, excessively high temperatures, bad drains and plumbing,” and lack of fire escapes were among the unpleasant and dangerous conditions inspectors found in Victorian factories. To combat this Dr. Canniff initiated factory inspections, “for the protection of the health and safety of the workers.”

In more recent times, medical officers of health have turned their attention to chemical exposure, lead poisoning, and the effects of second-hand cigarette smoke.