When he took office, Dr. Canniff had no staff, but soon he lobbied successfully for some help.

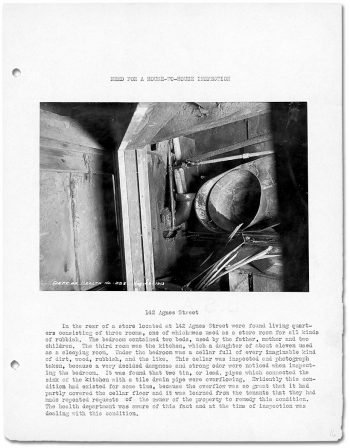

His first assistants were policemen, borrowed temporarily from the Police Department, and sent on house-to-house inspections to search for “insanitary evils,” that is, unsatisfactory disposal of human waste, dirty water, and garbage.

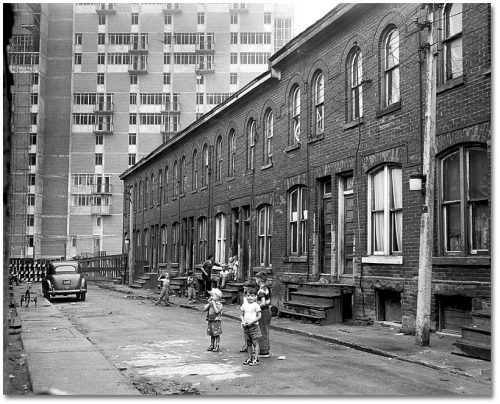

However, these efforts did not solve the larger problem of poor and expensive housing in the growing city. In 1911, Medical Officer of Health Dr. Charles Hastings studied the city’s housing conditions for himself, and published a report on what he bluntly called “slum conditions.”

As a result of Dr. Hastings’ report, the City demolished 1,600 substandard houses between 1913 and 1918.

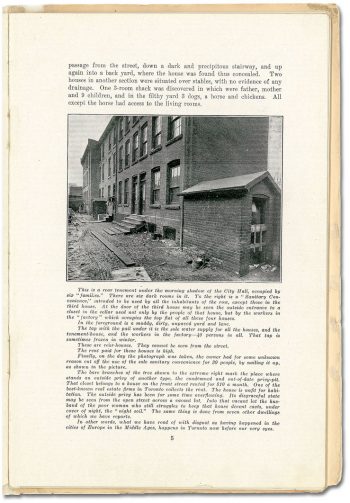

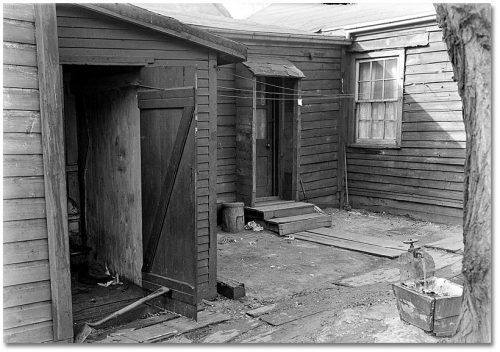

While the house below had both a flush toilet and running water, neither would have functioned during a hard winter freeze.

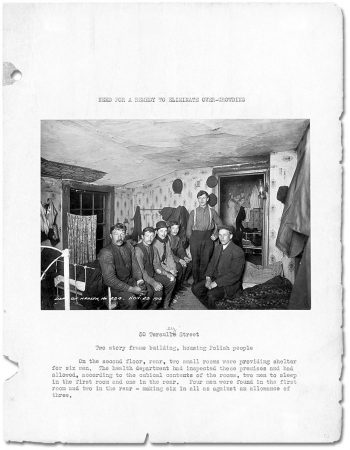

Dr. Hastings complained about a houseful of European workers in 1914, “They live cheap, work out all day, crowd into the houses at night, bring the mud of the streets into their homes, drink beer, play cards, and sleep, in the clothing worn during the day, in closed rooms. No cleaning ever attempted until brought to court.”

Early reports of the Department of Public Health acknowledge the need to provide assistance to the poor, but this charitable impulse was combined with a moral rectitude typical of the time.

In 1921, during a time of vast post-war unemployment, Dr. Hastings wrote that the department would give people coal, bread, and clothing, but not rent money, because “the family should bear some share of the burden of unemployment if their self-reliance was to be conserved.”

Dr. Hastings’ report signalled a growing understanding that “anything…which makes for poverty or destitution is a problem of public health.” At first, the Department of Public Health connected needy people with private social agencies such as churches and charities. By the time of the Depression, the City recognized the need for more government social services and created the Department of Public Welfare in 1931.