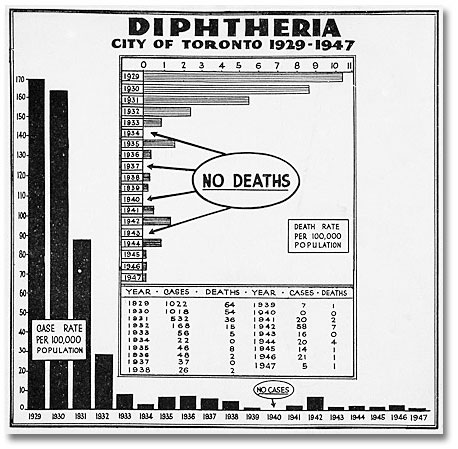

“No sooner had diphtheria been conquered and almost cast into oblivion than this new horror appears on the horizon,” wrote Medical Officer of Health Dr. G.P. Jackson in 1934. He was referring to polio, but he could have been talking about any new disease in history—smallpox, typhoid, scarlet fever, tuberculosis, diphtheria, polio, or AIDS. Every generation has its plague.

In the early 20th century, there was resistance to compulsory vaccination, even amongst some doctors.

Some people believed that vaccination was unproven scientifically, that it polluted the body, and that catching smallpox was unlikely in any case. Others feared that vaccination might cause them physical harm, and sometimes this did occur.

Vaccination then was more dangerous and painful than it is today. For example, smallpox vaccinations required scratching a patch of skin raw, and occasionally this led to sores that did not heal for weeks.

With better vaccination techniques and education, public opinion slowly changed, and in time vaccination of school children against a wide variety of diseases, including diphtheria, polio, and measles, became standard.

In 1937, Dr. Jackson observed that vaccination is a case in which “individual hazard is improved in direct ratio to the intelligent action of one’s neighbours.”

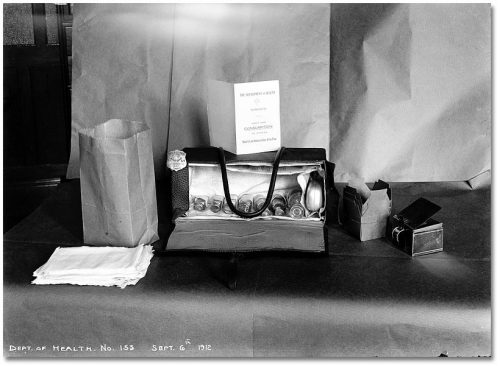

The Department of Public Health has always encouraged people to take charge of their own health. In 1912 Medical Officer of Health Dr. Charles Hastings introduced a “swat the fly” campaign to reduce the spread of typhoid from garbage to food via flies.

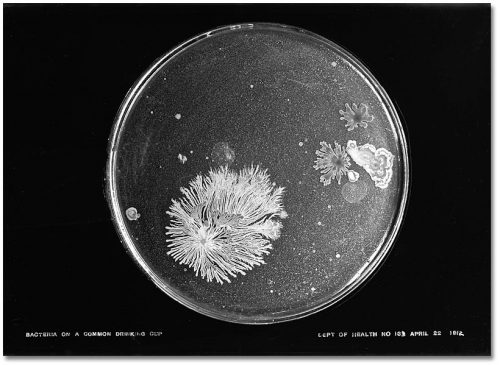

The three photographs below illustrate how the Department of Public Health used epidemiology (the study of what causes and spreads disease) to decrease risks in such common activities as drinking water.

The first photograph shows a drinking fountain with a tin cup chained to it that was used by every person who needed a drink. Horses used the large basin on the opposite side, and dogs drank from the basin near the ground. Dr. Canniff supported the installation of these fountains in the 1880s, saying that they prevented disease and, as a bonus, might deter people from going into saloons to quench their thirsts.

Canniff’s successor, Dr. Hastings, believed that this kind of fountain could spread disease and documented scientifically how the common drinking cup could pass bacteria and sickness from one user to the next.

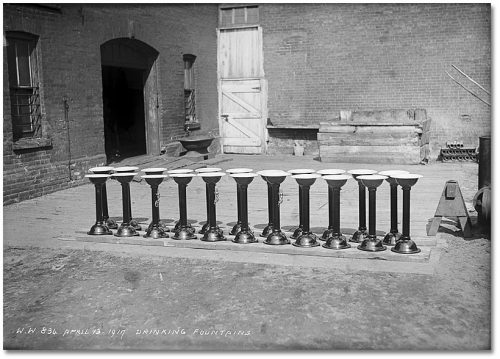

Hastings’ solution was the “bubble fountain”—the kind of drinking fountain we use today, where the drinker’s mouth touches only clean water. The fountains below are waiting for installation by the Department of Public Works.

The department knew it was important to trace the spread of diseases. Doctors were legally required to report to the medical officer of health when they learned of cases of infectious diseases such as typhoid and scarlet fever. However, many doctors didn’t know of the requirement, or didn’t bother.

Tracing people who may have been infected with disease required discretion and an understanding of the need to balance public health with the right to personal privacy.

Once a contagious illness was revealed, the department had the right to quarantine a household until the danger of infecting others was past. Stanley Barracks at Exhibition Place was used as civilian housing before and after World War II. Five families were quarantined there because one child had polio. The children shown here were pictured in The Globe and Mail newspaper for ignoring the quarantine and playing with other children.

As communicable diseases became less common, the need for quarantines declined. However, quarantine was used in 2003 to combat SARS and it is possible that new diseases in the future may bring it back into use.