The Department of Public Health saw the importance of educating women about the link between healthy pregnancies and healthy babies. In 1914, it set up prenatal programs to provide professional advice and encouragement.

The department tried to reach out to literally every mother and baby in Toronto, taking referrals from doctors, teachers, charitable workers, even neighbours. Public health nurses visited pregnant women at home and again after their babies were born.

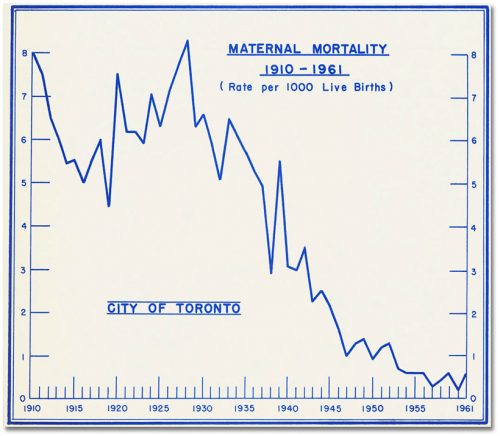

Within ten years, the rate of infant mortality had dropped by almost half.

Since many families could not afford to go to a doctor, the department also started free “well-baby clinics” where mothers could bring their babies for a medical checkup and advice on problems.

In 1914, Medical Officer of Health Dr. Charles Hastings wrote, “There are a large number of small children in Toronto whose mothers work every day, and who are dependent for their existence on the protection and care they receive from the Day Nurseries and Creches.” Children in day care were examined daily by a public health nurse, and weekly by a doctor at a child health clinic.

The department began to teach prenatal and baby care classes, including some aimed at fathers. The class shown below was probably sponsored by the Welfare Council of Greater Toronto.

In later years, the Department of Public Health expanded the scope of its parental education. Many earlier problems had diminished with the introduction of free medical care from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, school vaccinations, the availability of less expensive food, and advances in personal cleanliness due to widespread indoor plumbing. The department decided to pay more attention to helping parents increase their child’s emotional and psychological well-being.

“Too many mothers believe that if a child is reasonably well sheltered, does not go hungry, and shows no evidence of physical mistreatment, this is enough,” noted the department’s annual report in 1962. “Children need guidance, affection and praise from their parents; an opportunity to play and to express their feelings as well as shelter, food and clothing.”

The pamphlet to the right was created by the Manitoba Health Department, but was reprinted for use in Toronto. Toronto’s Department of Public Health reciprocated by providing information to other cities.

Medical Office of Health Dr. G.P. Jackson wrote in 1939 that Toronto was “well and favourably known throughout the American Health world and that in comparison with cities of similar size it ranks with the leaders in organization and accomplishment.” That sentiment continues today.