Donald Willard Moore (1891-1994), described by his friend and former Human Rights Commissioner Bromley Armstrong as “the leader, the gentle giant, the man with the iron fist in a velvet glove,” was a community leader and civil rights activist who fought to change Canada’s exclusionary immigration laws.

Donald Moore was born at Lodge Hill, St. Michael’s Parish, Barbados on November 2, 1891. His parents were Charles Alexander Moore, a cabinetmaker and member of the Barbados Harbour Police Force, and Ruth Elizabeth Moore.

At the age of 21, Moore left his family behind and emigrated to the United States, but soon left New York City for Montreal. He found work with the Canadian Pacific Railway as a sleeping car porter and his job brought him to Toronto. Moore earned enough to enrol in The Dominion Business College at 357 College Street, where he completed the courses necessary to allow him to register in the dentistry program at Dalhousie University in Halifax in 1918.

A lengthy bout of tuberculosis brought an end to Moore’s formal education and his hopes of becoming a dentist. In need of money, he took a job as a tailor, a trade he had learned in Barbados. In 1920, Moore began working at Occidental Cleaners and Dyers, located at 318 Spadina Avenue between St. Patrick Street (now Dundas Street West) and St. Andrew Street. Eventually he was able to purchase the business.

Moore’s store was a gathering place for the West Indian community. It was there that the Toronto branch of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association was established, as well as the West Indian and Progressive Association and the West Indian Trading Association. Moore would continue to operate his business in various locations until his retirement in 1975

In 1951, Moore founded what came to be known as the Negro Citizenship Association, a social and humanitarian organization with the motto, “Dedicated to the promotion of a better Canadian citizen.” The association sought to challenge the systematic denial of black West Indians seeking legal entry into Canada and to bring an end to the incarceration of individuals who were awaiting either deportation or decisions on deportation order appeals.

On Tuesday April 27, 1954 Moore led a delegation to Ottawa, which included 34 representatives from the Negro Citizenship Association, as well as unions, labour councils, and community organizations. They presented a brief to Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Walter E. Harris.

The brief drew public attention to Canada’s discriminatory immigration laws, which denied equal immigration status to non-white British subjects, described the impact of those laws, and made specific recommendations for change.

The Immigration Act since 1923 seems to have been purposely written and revised to deny equal immigration status to those areas of the Commonwealth where coloured peoples constitute a large part of the population. This is done by creating a rigid definition of British Subject: ‘British subjects by birth or by naturalization in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand or the Union of South Africa and citizens of Ireland.’ This definition excludes from the category of ‘British subject’ those who are in all other senses British subjects, but who come from such areas as the British West Indies, Bermuda, British Guiana, Ceylon, India, Pakistan, Africa, etc…Our delegation claims this definition of British subject is discriminatory and dangerous.

Excerpt from the Negro Citizenship Association’s brief to the Citizenship and Immigration Minister

The landmark brief and the subsequent relaxation of immigration laws opened the door for West Indian nurses and domestics to find employment in Canada. By 1955, Moore’s work with the governments of Jamaica, Barbados, and Canada enabled domestics to gain permanent residency after one year of work.

In 1956, Moore and two other members of the Negro Citizenship Association purchased a 12-room house on Cecil Street and converted it into a recreation centre for the West Indian community called Donavalon Centre.

In addition to serving as the home of the United Negro Improvement Association and the Toronto Negro Citizenship Association, the Donavalon Centre offered a range of activities and services, including dances, teas, Sunday programs, insurance for its members, and the publication of a quarterly newsletter.

In 2000, the City of Toronto Culture Division erected a plaque at 20 Cecil Street to commemorate Moore’s significant contributions.

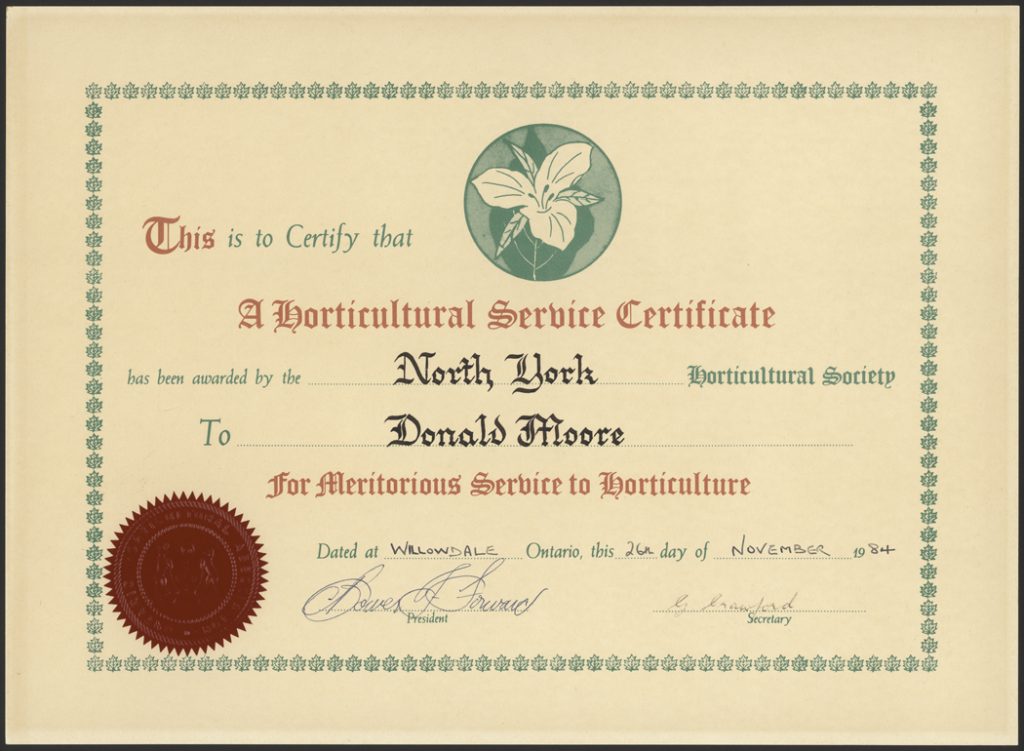

Moore retired from business and public life in 1975. In his later years, Moore became an avid gardener. An award-winning member of the North York Horticultural Society, Moore cultivated a beautifully landscaped garden and lush greenhouse at his home on Drewry Avenue, a home he built himself not long after purchasing the undeveloped two-acre lot back in 1942.

Moore was the recipient of a number of awards for his significant contributions to the West Indian community and to Canadian society, including the City of Toronto Award of Merit (1982), the Ontario Bicentennial Medal (1984), the Harry Jerome Award of Merit (1984), the Barbados Service Medal (1986), the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship award (1987), the Order of Ontario (1988), and the Order of Canada (1990).

In August 1994, Donald Moore died in his sleep at the age of 102. He is buried at Sanctuary Park Cemetery in Etobicoke. He left behind Kay, his wife of almost 30 years, his son Desmond, and his stepchildren Karlene, Lawson, and Betty.