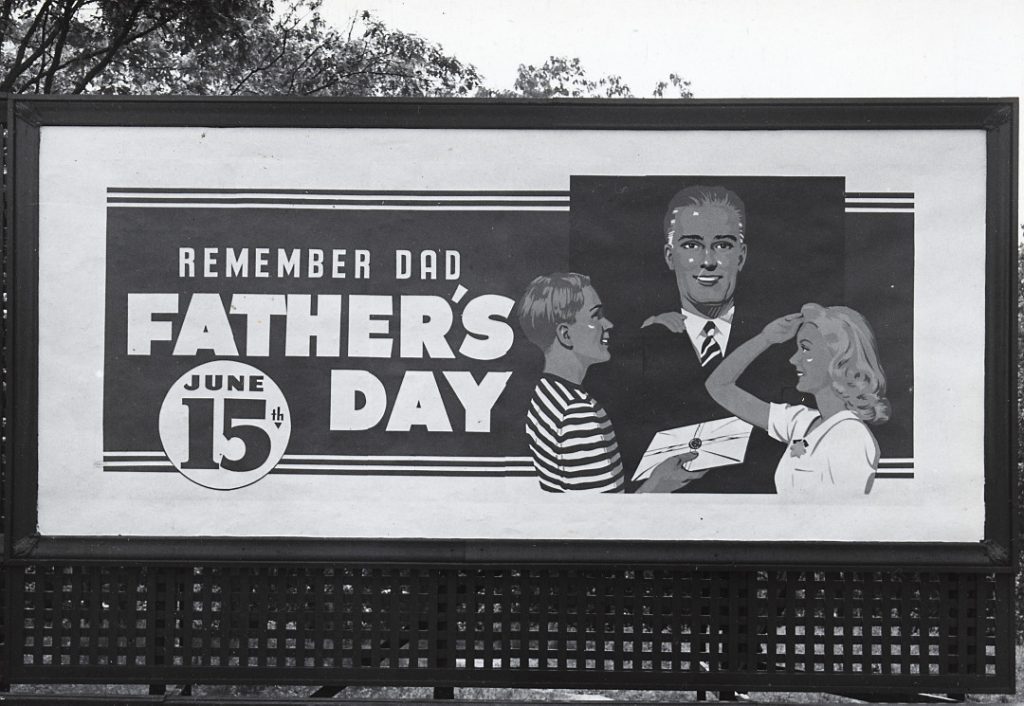

One sure signal that the long, warm days of summer are fast approaching is the appearance of ads to “remember Dad” on the third Sunday in June. Father’s Day is not only a day to cherish one’s father; you are also encouraged to get dad a special gift. This might be a new barbecue, fishing gear, power tools, a big screen television, or the old favourite—a new tie.

The idea of Father’s Day first came to Sonora Smart Dodd of Spokane, Washington. She and her siblings were raised solely by their father, and every Mother’s Day Sonora lamented the lack of a day to celebrate fathers. The first Father’s Day was held in Spokane on June 19, 1910. Informally acknowledged by President Calvin Coolidge in 1924, Father’s Day was not officially proclaimed in the United States until 1966, although not as a statutory holiday. Since the 1920s, Canadians have also marked Father’s Day, but here too it has not received any official recognition. Many other countries do likewise, although a few European countries align the celebration with the March religious feast of St. Joseph, the patron saint of fatherhood.

In Toronto, a leading promoter of Father’s Day was haberdasher Norman Birrell, who lived from 1890 to 1965. Norman was a gifted salesman, who had several menswear stores in Toronto. One of his sons, John Birrell, recounted the story of how Norman contracted with a local ice company to have a straw boater hat frozen into the middle of large block of ice. On a sizzling summer day, the ice block was placed on the sidewalk in front of Birrell’s store on Bloor Street West. As the ice dripped away in the heat, the frozen boater attracted a large amount of attention from passers-by. The clever clothier achieved his goal of increasing sales when dozens of boaters were peddled that day.

Norman Birrell lived at a time when men dressed more formally. Everyone wore a hat, regardless of social standing. Neckties, belts, walking sticks, cufflinks, handkerchiefs, and other male furnishings were items that found a ready market.

However, while business might be brisk most of the year, the summer months tended to be a slack period for sales. Birrell’s genius was to become an early enthusiast for the promotion of Father’s Day in Canada. In 1936 he took on the role of chairman of the Toronto Father’s Day Committee, an ad hoc group of businessmen eager to market their wares. Promotion of this holiday was seen as good for business while the Great Depression dragged on, with retailers aiming for a “second Christmas in June.” As Birrell told the Toronto Star in June 1936, to honour some 10,000 Toronto fathers, “wives and children will go shopping, more than 600 extra persons will have to be employed in Toronto to handle the business, and everyone from shopkeeper to father will be happy.”

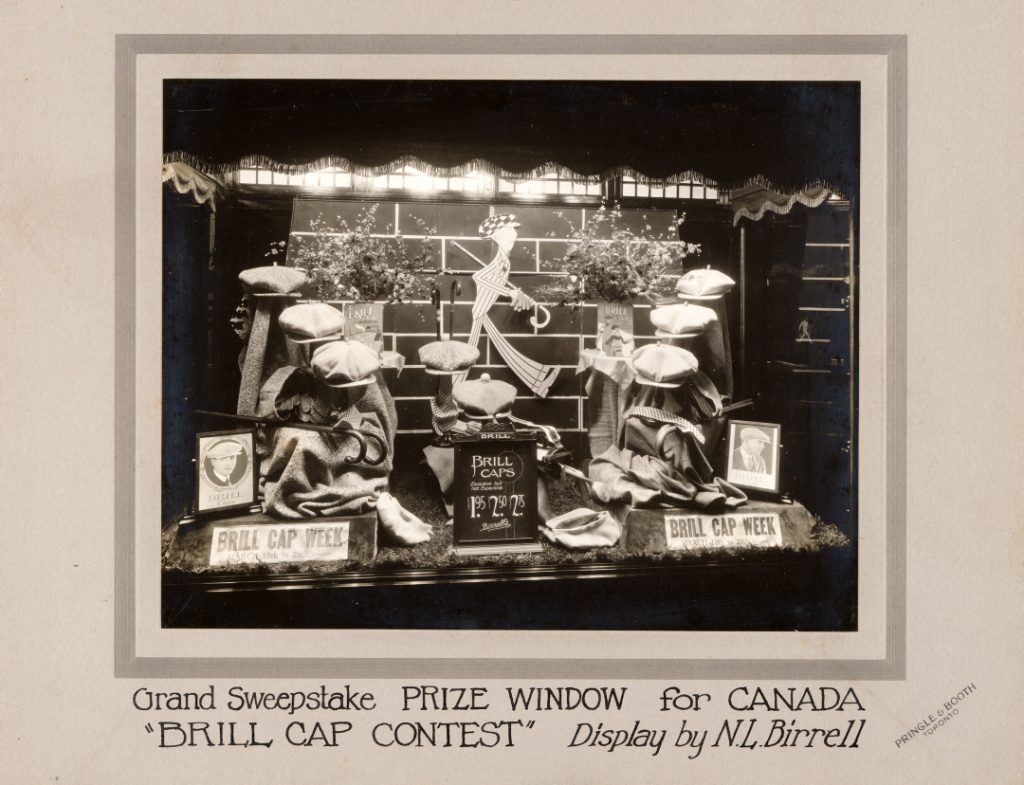

Norman Birrell was also an accomplished window decorator at his various shops. He took a great deal of care with his displays, and his talent and efforts were recognized by colleagues in his business community who awarded him several commendations.

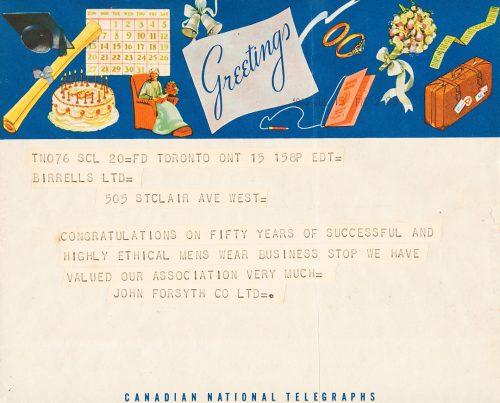

Birrell was the chairman of the Toronto Father’s Day Committee for 15 years, finally stepping down in 1952. That year, at a King Edward Hotel tribute, his fellow menswear merchants celebrated him as “the Father of Father’s Day” for his tireless promotion of the holiday and for the success that it brought to the industry.

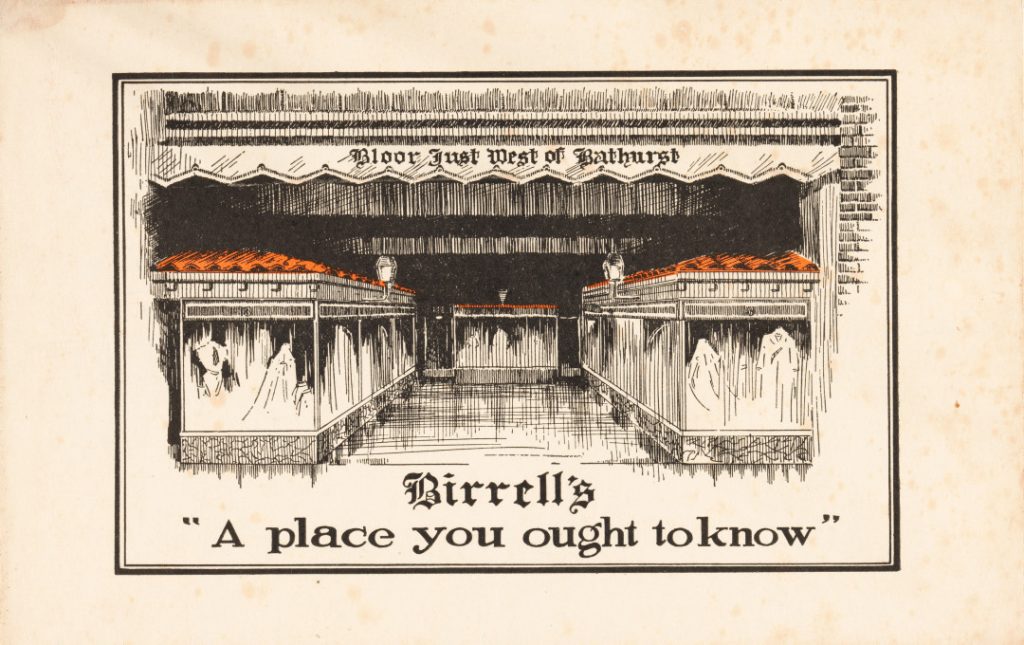

Norman Birrell was a business man and shopkeeper for fifty years. His first store was opened in 1914 at 562 Bloor Street West, just west of Bathurst. Considered his flagship store, it remained open until 1950. Birrell opened additional stores, including one on Bloor near Westmoreland Avenue (open until 1951), and another one at 66 Vaughan Road near St. Clair Avenue West (1939 to 1962). In 1964, Birrell expanded into Thorncliffe Park mall in East York.

After Norman’s death in 1965, his sons Neville and John took over the business, opening one final store in 1978 at Scarborough’s Bridlewood Mall. By that time however, generational and demographic changes were steering men’s fashion tastes towards a more casual look, even in the workplace. Thus the demand for formal wear, especially hats (which few men wore after 1960) declined; the last Birrell’s store closed in 1983.

With his stores now a distant Toronto retail memory, the annual occurrence in June of the day he so actively promoted remains part of Norman Birrell’s legacy.