Commercial and Industrial Toronto

By 1832, a year before Howard moved to York, the town had displaced Kingston as Upper Canada’s leading urban centre, with an economy partly based on serving a hinterland that extended out in a 60-kilometre arc in the pre-railway era as lumbermen and farmers cleared the forests and transformed the colony’s landscape. The town’s expanding port and road connections facilitated economic growth, helped further by something of a transportation revolution marked by the coming of steamships on Lake Ontario (1816), the opening of the Erie and Welland canals (1825 and 1833), and by less dramatic developments, such as the macadamization of part of Yonge Street (1830s).

Industrial output remained modest in Toronto before the 1860s, with few operations expanding beyond workshop enterprises to meet local needs. Yet, portents of the future could be seen as early as the 1830s with the introduction of steam-driven machinery in some businesses. Dramatic change began once the railway arrived in the 1850s, bringing with it modern industrialization, the filling in of the waterfront, and a corresponding growth in banks, white-collar businesses, consumerism, and new class and social structures.

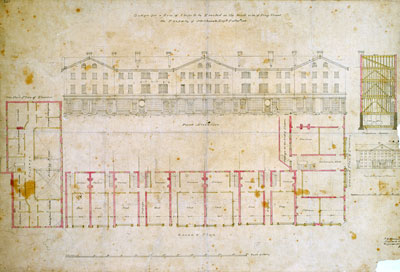

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.60.

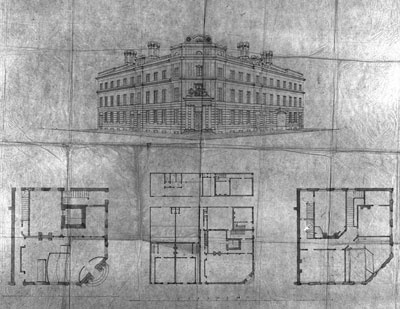

The Canada Company purchased a million hectares of land from the Crown to resell or lease to settlers beginning in the 1820s. The company’s holdings were concentrated mainly in the Huron Tract of today’s southwestern Ontario, and thus the Canada Company is a good example of how Toronto-centred businesses exerted influence throughout the province. The Howard-designed building of 1834 stood on the east side of Frederick Street between King and Front. Its design followed the architectural norm in late Georgian Toronto, being a balanced centre-hall Neoclassical structure.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.61.

The large building on the southeast corner is the Chewett Building, designed by John Howard in 1833. When built, it was the community’s first office block and the largest single structure in town. It included offices, shops, residences, and the British Coffee House (a hotel). For a time, John and Jemima Howard maintained an in-town residence there.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 201.

The Chewett Building was typical of 19th-century urban commercial construction: it took maximum advantage of the land available, with narrow ground floor shops built to the lot line, and with storage, offices, and apartments located above. Howard designed other commercial blocks and smaller one- and two-shop retail facilities in Toronto and elsewhere in the province.

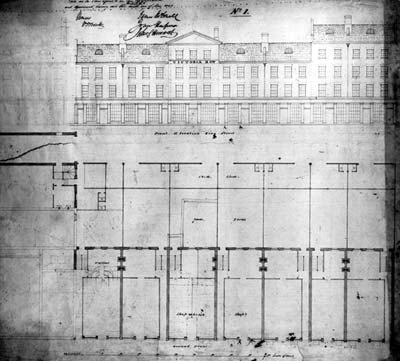

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 221.

Another Howard-designed commercial project was Victoria Row, on the south side of King Street, west of Church. It was built in the early 1840s for James McDonell, a government clerk who had inherited property in the city and who wanted to exploit its financial potential. (Note the toilet facilities in the rear sheds.)

Toronto Public Library (TRL), T 12638.

This photograph shows Victoria Row after being modernized in the Second Empire style in the 1860s. We might wonder what John Howard thought of the changes as architectural tastes moved beyond those of his frmative years.

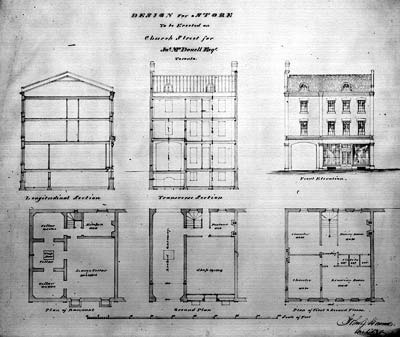

1839? (JH) Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 248.

This plan contrasts with the other Howard store designs above because it is a much smaller structure. Note how he used space efficiently, how a trap door in the driveway allowed for loading goods into the cellar, and how he laid out the domestic and retail spaces.

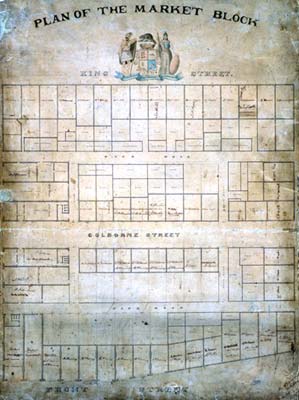

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 819.

This map depicts the area between St Lawrence Market and Church Street shortly before the Great Fire of 1849. It consisted largely of rows of masonry buildings facing the streets (heavy lines), and lesser, mainly wood buildings facing the laneways (thin lines).

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 239.

This impressive Howard-designed bank dates to 1845-46 and stood at the northeast corner of Yonge and Wellington streets. Howard called the architecture ‘Modern Greek,’ which he interpreted loosely, and which mimicked Sir John Soane’s Bank of England in London (in a modest way), presumably to convey a sense of reliable gravity to the bank’s clients.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), T 10463.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 767.

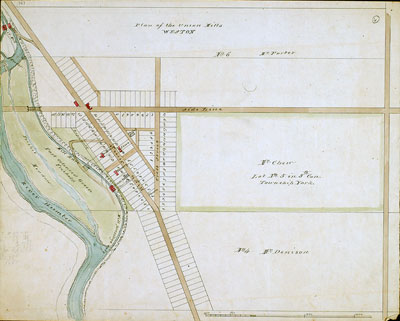

Today’s Toronto incorporates dozens of older communities. Weston was one, a semi-rural village that grew along the Humber River as a result of pre-modern industrial activity that used waterpower. During this era Howard designed mills and other industrial buildings outside of urban Toronto. A major shift occurred with the coming of wood- and coal-generated steam power (especially from the 1860s) because factory owners then could concentrate their operations in emerging railway centres, such as Toronto and Hamilton.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.51.

This view shows Taylor’s Wharf at the foot of Frederick Street (in the mid background) and the Gooderham windmill (right background). The mill was unusual because most industry in Georgian Canada favoured waterpower.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 825.

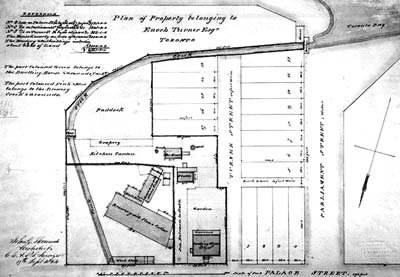

Toronto’s famous brewer (and founder of his eponymous free school) had property at the southeast corner of Palace (Front) and Parliament streets. The orientation of the plan is upside-down, with ‘south’ being at the top. Note how Turner’s business and home sat in close proximity to each other. That was common before later industrialization led wealthy producers and merchants to segregate their homes in neighbourhoods away from their enterprises and their workers.

Among the many features on this map, perhaps the most interesting are the proposed railway lines. When railways came to Toronto, the undeveloped linear creek valleys became access routes to bring trains into the heart of the city. Note the original base of Dundas Street (now Ossington Avenue south of Dundas).

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 737.