Institutional Toronto

Urban Toronto had its birth in 1793 when a threatened American invasion led British officials in Upper Canada to establish a naval arsenal by the shores of Toronto Bay, build Fort York to defend it, attract a civilian population to supply the military with goods and services, and move the colonial capital here from the exposed border town of Niagara.

When John Howard moved to ‘York’ 40 years later, the community had evolved from a backwoods outpost into the province’s largest centre. Yet much of its prosperity and character still came from its status as the capital and as a garrison town, as well as in attracting businesses, institutions, and professionals with a colony-wide interest. In 1834, a year after Howard’s arrival, the province incorporated the town as the ‘City of Toronto’ in order to create a municipal structure to meet the needs of an urbanizing population.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.30.

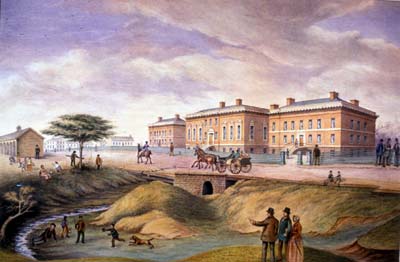

The Upper Canadian parliament buildings, designed by Thomas Rogers and constructed between 1829 and 1832, stood at Front and Simcoe streets. The surrounding area was largely a mixed institutional and affluent suburban district that had emerged after the War of 1812. However, less prestigious structures, such as immigrant sheds and taverns, stood nearby, as sharp neighbourhood distinctions did not exist in Georgian Toronto.

The parliament buildings overlooked Toronto Bay before the waterfront began to be filled in with the coming of the railways and modern industrialization in the 1850s.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.95.

Howard’s watercolour records a luncheon held in the prayer hall of Upper Canada College near the parliament buildings. The event celebrated the laying of the cornerstone for King’s College, a post-secondary educational institution in today’s Queen’s Park (and the forerunner of the University of Toronto). Although governed and subsidized by the province, UCC and King’s fundamentally were Anglican institutions. They represented an attempt to make the Church of England the ‘established’ church in the province. However, the population was too diverse and the times were too liberal to achieve that goal. King’s became the non-sectarian University College in 1850, while UCC became non-denominational and eventually lost government funding in 1900.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.40.

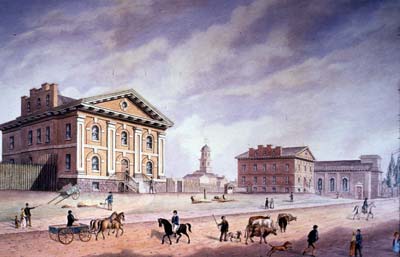

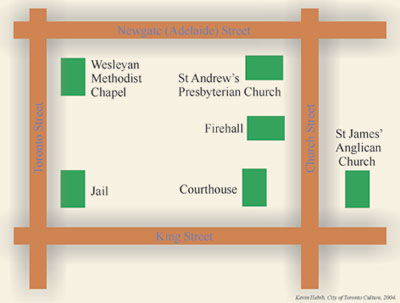

John Howard’s watercolour depicts the 1824 jail, the 1835 fire hall (by Howard), the 1824 courthouse, and the 1833 Anglican church of St James. These public buildings marked the importance of both governmental and other organizations in Toronto. For instance, when the Church of England created the Diocese of Toronto in 1839, it was natural that St James’ would become the cathedral and that its rector, John Strachan, would be consecrated bishop.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), 938-1-2.

The Howard-designed ‘Home District Gaol’ stood at the southeast corner of Front and Berkeley streets (but the courthouse was not built). Constructed between 1837 and 1841, the jail’s design followed 18th-century British precedents, being a ‘panopticon,’ which allowed guards at the centre of the building to monitor the cell wings with ease. The Don Jail replaced it in the 1860s except for a brief period of military use in 1866-67 to house prisoners taken during the Fenian Raid.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Arts Services, A75-77.

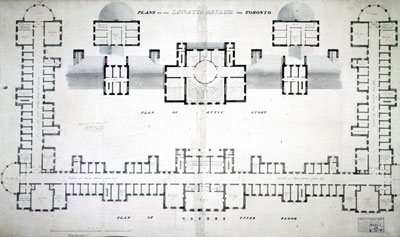

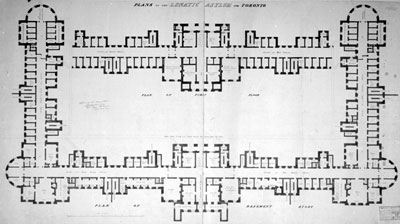

The Provincial Lunatic Asylum was Howard’s greatest building project. Architecturally, the inspiration for the main façade was the National Gallery in London, completed shortly before Howard moved to Canada. (The portico, however, was not built and another architect constructed the southward-projecting wings in the 1860s to a different design.) Before the asylum opened in 1850, the mentally ill either lived with their families or in jails, but received little, if any, professional care.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), T 10965.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 423.1.

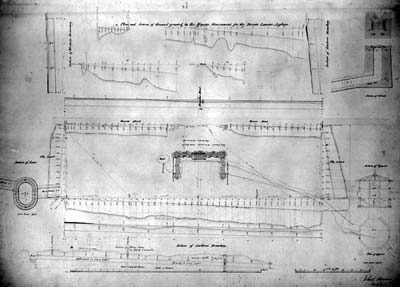

This map shows the land set aside for the asylum along Queen West (at today’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health). In developing the facility, Howard studied contemporary literature on asylums and visited similar buildings in the United States, as well as investigated new developments for providing water, heat, light, and ventilation in large buildings.

Archives of Ontario/Archives de l’Ontario, AO3267.

Patients were divided by gender and by the severity of their conditions. Each treatment unit was self-contained, with such facilities as a dining room serviced by dumbwaiters from the basement kitchens. Amenities included Protestant, Roman Catholic, and non-denominational chapels as well as a ballroom where patients could exercise and socialize. Corridors did double duty as recreational and visiting areas, and sunrooms overlooked the grounds. The land around the building contained gardens where patients worked to help reduce operating costs and to engage in healthy outdoor labour as part of their treatment.

While this plan conveys the order and rationality of Howard’s concern to create a worthy public asylum, much of the idealism behind his design was lost when the full facility was not built, the number of patients admitted exceeded capacity, and understaffing and other problems subverted the care offered.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 411.

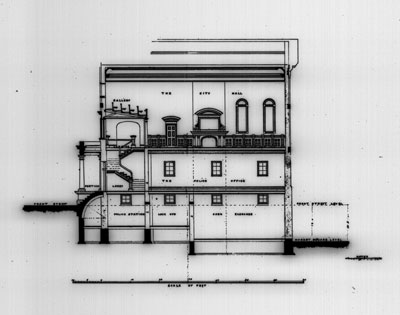

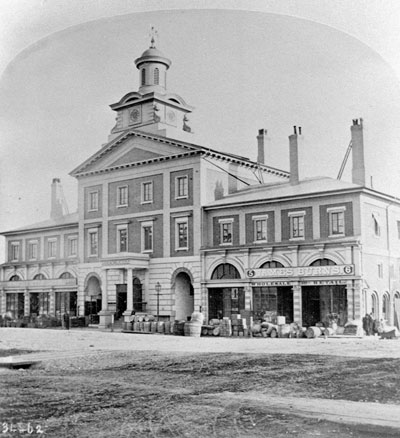

This was Toronto’s second city hall, built in 1845. While the drawing is Howard’s, the architect was Henry Bowyer Lane, who produced a sort of Palladian building. Known as the ‘New Market House’ it served as city hall until 1899. Howard competed to be the architect to renovate the building; however the job went to another, William Thomas.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), T 11786.

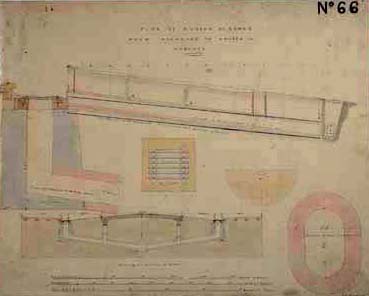

City of Toronto Archives, PT169C-66.

Public works projects were part of Howard’s duties as city surveyor. These plans are typical of those he created and show the standard Toronto gravity-fed sewer lines of the period. The 1840s and 1850s saw a recognizably modern city begin to take shape. This was due partly to population growth, but also to the innovations of the Victorian era, such as the installation of sewers and the other mundane elements that made urban life congenial. For example, gas home and street lighting came in 1842. A waterworks opened at about the same time, although it was intended primarily to help fight fires. (Private wells and carted water remained common, while health problems associated with bad water persisted for decades to come).

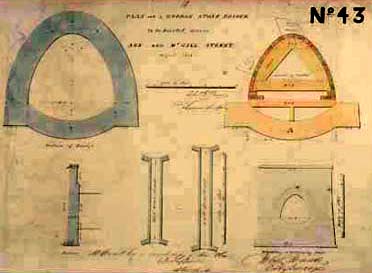

City of Toronto Archives, PT169-43.

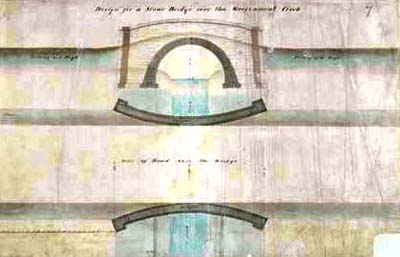

Howard designed bridges, levelled and paved roads, built sidewalks, and carried out other engineering duties to subdue the landscape to meet the needs of a growing urban centre. This bridge design was a standard one used to carry small streams under road surfaces.

The location of this bridge is uncertain, but with its Picturesque aesthetic, it is a more elaborate design than the one across Ann and McGill streets. (It may have been designed to improve access to the garrison lands leased from the military by the City for a park. If so, the bridge may have been built on the line of King Street, west of Bathurst.)