Spiritual Toronto

Toronto in the 19th century was a religiously diverse community, although the majority of people were Protestants, embracing, for instance, 73 per cent of the population in 1851. However, within Protestantism there was tremendous divergence, as exemplified by the differences between High Anglicans and Evangelical Baptists. At the same time, Toronto’s Roman Catholic population was sizeable (25 per cent in 1851). Other people also made their contributions to building the cultural mosaic of the mid Victorian city, as represented religiously by a modest number of Jews, Unitarians, and freethinkers.

John Howard’s architectural output for Toronto’s religious communities was small, with the bulk of his ecclesiastical efforts being focused outside the city, where he designed churches for various denominations, although most of his work was for his own Anglican church. His best-known religious buildings were Holy Trinity Chippewa (1840), Christ Church Tyendinaga (1843), and St John’s York Mills (1843).

Toronto Public Library (TRL), 34503.

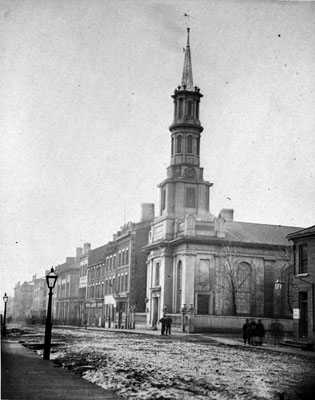

Today, St James’ Cathedral at the corner of King and Church is a magnificent Gothic Revival building from the 1850s. However, this earlier structure – built in 1833 but lost to fire in 1839 – was Neoclassical (designed by Thomas Rogers of Kingston). It captured a different view of the faith, of the rational and light-filled belief of the Georgians, in contrast to the mystical and transcendent religion of the Victorians. (Rogers’ tower, although planned, was not built.)

Toronto Public Library (TRL), JRR 1138.

This building at the southwest corner of Church and Adelaide streets dates to 1830-31. The architect was John Ewart, but John Howard added the tower and spire in 1840 and also enlarged the church. Its architecture captured a loose interpretation of the Greek Revival design popular in Edinburgh, the emotional home of Canadian Presbyterianism (and a city referred to as the ‘Athens of the North’ because of the quantity of such architecture in the Scottish capital).

Toronto Public Library (TRL), 34503.

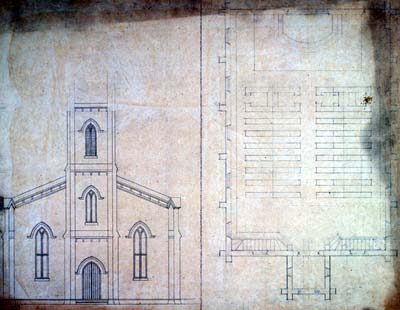

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 314.5.

Howard designed a number of very similar churches in the early days of the Gothic revival in Canada, including St John’s York Mills of 1843, which closely matches this drawing. Unlike slightly later, more authentic Gothic Revival churches, Howard’s early ecclesiastical buildings fundamentally were Georgian ‘preaching boxes’ with some Gothic detailing. However, they represented a change from the earlier generation of Neoclassical houses of worship. Part of the transformation came from the liturgical and cultural developments of the time as well as an emerging view that the Gothic architecture of Mediaeval Christianity was more suitable for churches than the Neoclassical designs of pagan Antiquity.

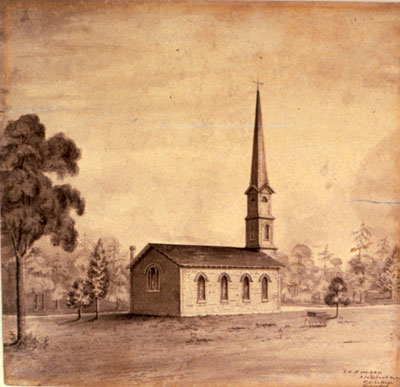

Toronto Public Library (TRL), JRR 3380.

The first St Paul’s dates to 1841 and stood on Bloor Street, between Church and Jarvis. Howard designed the spire and made other renovations shortly after its construction. In 1861, after the parishioners built a new Gothic Revival stone building, they moved this wood structure on log rollers to a spot around modern Bay Street, where it became St Paul’s Chapel-of-Ease, or Old St Paul’s. In 1871 it became the home of the separate parish of the Church of the Redeemer until replaced by today’s Gothic building in 1879 at Avenue Road and Bloor.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), T 10597.

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 913.

St James Cemetery – located southeast of Parliament and Bloor streets – replaced the graveyard that surrounded St James’ on King Street. Howard’s design generally followed the newly developing principles for Picturesque ‘rural’ cemeteries that largely supplanted the churchyards of Georgian times. For instance, planting mournful-looking willows, hemlocks, and other trees satisfied the Victorian aesthetic for a Picturesque cemetery, while the pathways encouraged people to meander through the grounds. Like other such burial grounds, it served as a kind of park until modern parks began to appear a generation or so later.

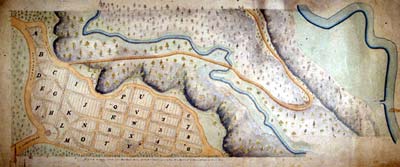

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 756.

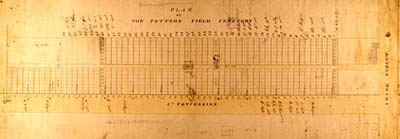

The Potter’s Field was located west of Yonge along the north side of Bloor (then known as the First Concession). It received 6,700 burials between 1825 and 1855. After it closed, remains were moved to Mount Pleasant and Toronto Necropolis cemeteries.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.42.

John Howard designed this tomb in High Park for his wife and himself in 1874-75. (Jemima Howard died in 1877 and John passed away in 1890). Like Colborne Lodge, this was a romantic structure, but it represented a heavy Victorian romanticism in contrast to the lighter version articulated in his Regency lodge.

City of Toronto Toronto Culture, Museums and Heritage Services, 1978.41.36.

This view of the tomb shows its famous railing, designed by Sir Christopher Wren in 1714 for St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Howard bought the fence when it was taken down and had it shipped from England. Sadly, some of it was lost at sea, with only enough for one side of the tomb being preserved for installation late in 1875. There are two small brass plaques on the railing. One records the birth and death dates of the Howards. The other contains the text: ‘Saint Paul’s Cathedral for 160 years I did enclose’ and these thoughts on the Fall of humanity: ‘Oh! Stranger look with reverence. Man, man, unstable man, it was thou who caused the severance.’