Romance Underfoot

One of the most common decorative features in Toronto homes between about 1880 and 1940 was the Oriental carpet. Spadina, Toronto’s grand historic house museum, displays an interesting collection of such carpets. Our web exhibit, Romance Underfoot, explores these rugs and their place within the larger context of Torontonians’ fascination with these colourful and popular artifacts.

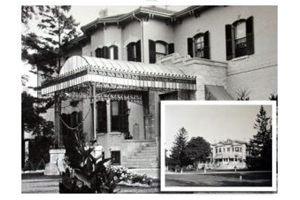

James and Susan Austin built Spadina as their Toronto family mansion in 1866 on the foundations of the former Baldwin estate of 1818. Upon the death of James in 1897, Spadina became the home of Albert and Mary Austin and their five children. The new inhabitants redecorated and remodelled Spadina to suit their tastes, with Mary in particular expending considerable energy in the project. Guided by her personal aesthetic, the family purchased the majority of its decorative arts and furnishings from dealers in Toronto. Despite their wealth, the Austins’ Oriental rug purchases were not extravagant. Rather, they acquired pieces that were typical for middle-class households across the city. Hence, their collection of carpets speaks to the larger decorative experience of Torontonians of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Orientalism

The ‘mystique’ of the Orient was in vogue in the Western world by the 1880s. The fascination with the ‘exotic’ established an aesthetic inclination that people embraced with considerable enthusiasm as it influenced Western design, from book covers to ceramics to household items.

Department stores and other retailers of the 1880s-90s responded to this interest by selling such inexpensive objects as Oriental rugs (both real Middle Eastern handmade carpets and Western manufactured copies). Thus, the middle class could indulge in this latest home fashion trend without spending a lot of money. People in the late Victorian era typically placed Oriental rugs on top of wall-to-wall carpeting in front halls, drawing rooms, and bedrooms as practical and fashionable additions to their homes.

Many other examples of Orientalism can be seen throughout Spadina today.

City of Toronto Collection; photograph by Neil Brochu.)

Right: Middle Eastern coal heater, early 20th century.

(1982.7.683; City of Toronto Collection; photograph by Neil Brochu.)

added a Moorish element to the second floor. (Photograph by Neil Brochu.)

Department Store Carpets

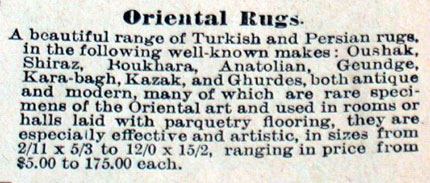

The 1889 Eaton’s catalogue sold rugs of genuine Eastern origin under the names ‘Mecca’ and ‘Dagastan,’ based on the assumed points of origin of hand-made textiles, or, in the case of rugs titled ‘Smyrna,’ a Turkish port from which they had been sent to Europe and North America.

The Spadina collection has a number of rugs that likely date to this period. The earliest known insurance inventory of the home, from 1899, includes 11 rugs, without distinction between domestic and Oriental carpets, although both types likely were present in the home. The inventory lists carpets in all of the principal rooms and hallways of the house. Most carried insurance values of between $10 and $25, amounts that illustrates how Toronto families could follow the movements of popular taste without extravagance.

Carpets of the late Victorian period generally originated in Turkey and the Caucasus, were small in size, and were constructed of wool pile on wool warp and weft. The patterns presented bold geometric designs and could be standardized. However, closer inspection reveals seemingly idiosyncratic drawings that indicate evidence of the artistic individuality of the weavers.

Scholarship

Oriental carpets maintained their popularity across the turn of the 20th century. At that time, scholarship on rugs became more refined and appreciation of the artistry of carpet-making grew.

One consequence of developing connoisseurship was that older labels for carpets, associated with generalized points of origin, were replaced with names that corresponded more closely to the carpets’ tribal pedigrees. Rugs indiscriminately sold earlier as ‘Dagastan,’ for instance, now were marketed under such names as ‘Kabistan,’ ‘Shirvan,’ ‘Chichi,’ and ‘Derbend.’

The 1901-02 Eaton’s catalogue mirrored the academic trend. Rather than listing Oriental carpets generically, such as ‘Mecca’ or ‘Smyrna,’ it used more refined names that still are in common parlance, such as ‘Oushak,’ ‘Boukhara,’ and ‘Kazak.’

Household Cleanliness

Consumers prized rugs from the Orient for their beauty in terms of colour and design, considered them to be more durable than other carpets, and thought they would retain their value better than domestic rugs. Another important reason why consumers chose Oriental carpets around 1900 was their association with cleanliness. New concerns over household sanitation and health motivated many homeowners to pull up their wall-to-wall carpeting and either varnish their floorboards or install hardwood. These dark glossy surfaces proved to be ideal settings for Oriental carpets, which could be dusted easily or sent out for cleaning.

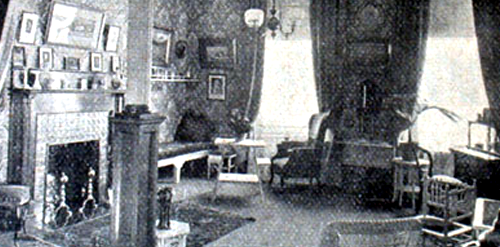

These interior photographs appeared in a 9 January 1915 Saturday Night article that featured the Austin family home. The gleaming hardwood floors had been installed eight years earlier. A large selection of the family’s small Oriental rugs are scattered among the bearskin mats.

The Consumers Gas Company took these photographs of other Toronto interiors in the 1920s and 1930s. Note the large Oriental rug in the living and dining rooms.

Newcomers to the Toronto Carpet Trade

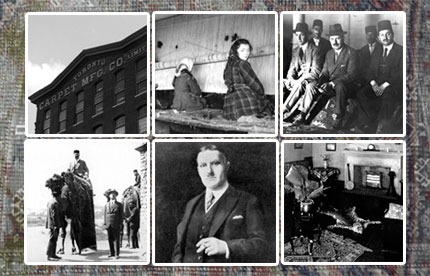

Armenian immigrants in the late 19th century established the first serious Oriental rug trade in North America to compete against the department stores. They were knowledgeable dealers, and generally could import better quality rugs through their connections in the Middle East than their competitors could.

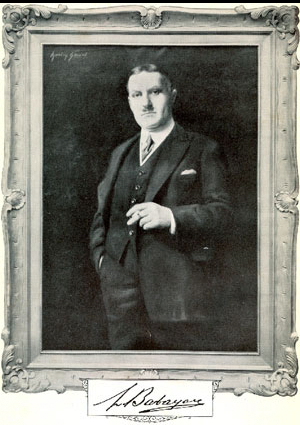

Levon Babayan was the first Armenian dealer in Toronto. He opened Babayan’s Limited in 1896 to sell, clean, and repair Oriental carpets. His company had representatives throughout the Middle East who secured rugs in bundles of 50 to 1000, ranging in quality from good to bad. A shipment typically took between four and six months to reach Toronto after travelling from the villages where they had been woven to Baghdad or to the Persian Gulf for shipment to Constantinople, where they were sent on to Europe and North America. Upon their arrival in Canada, the government imposed a 40 per cent duty on them. Generally rugs from India were not sold in Canada, but Babayan made them available to consumers who wanted to acquire them.

Babayan published The romance of the Oriental rug, a book that offers insights into the local rug trade of his day. He stressed the seriousness of the proper care of Oriental rugs, asserting that maintenance neither should be taken lightly nor entrusted to the care of household servants. In his opinion, the ‘Persian process,’ supervised by the ‘native experts,’ was the only reliable method of carpet cleaning.

In his book, published in 1925, Levon Babayan noted that ‘Over the last 15 years the demand for Oriental Rugs has enormously increased throughout Canada, and the general public has been educated gradually to buy the better class of Rugs, such as Kirmanshahs, Sarouks, and Kirshans or rare Boukharas.’

(The romance of the Oriental rug.)

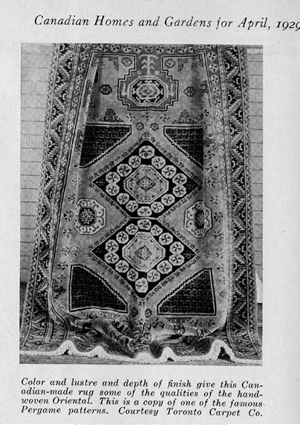

(Canadian Homes and Gardens, April 1929.)

Department Stores Hang On

Despite competition from specialty shops, department stores continued to sell Oriental carpets. They sent their own buyers to the Middle East and dealt with carpet agents there to secure stock for their stores. Buyers from Toronto’s Robert Simpson Company photographed these images in Turkey in the early 1930s.

(Estate of Eric Cecil Budd; City of Toronto Collection.)

(Estate of Eric Cecil Budd; City of Toronto Collection.)

(Estate of Eric Cecil Budd; City of Toronto Collection.)

Imitation Oriental Rugs

Spadina and other Toronto homes also possessed factory-made copies of Oriental rugs. An insurance inventory taken by Mary Austin in 1916 listed two imitation Persian carpets in the drawing room. These rugs were more affordable than authentic ones, but looked much like genuine floor coverings from the Middle East. While manufacturers may have replicated many of the physical qualities of true Orientals, they nevertheless could not capture the mystique and romance of the genuine article.

(Photograph by Neil Brochu)

The Conservative Tastes of the Austins in a Changing World

By the 1930s ideas of modernization had gained acceptance in the minds of some Canadian householders. The pages of Canadian Homes and Gardens during that decade illustrated the tension between the thrill of being up-to-date and the comfort found in embracing the traditional. While Oriental carpets remained as staples in traditional home décor, people with more modern tastes purchased rich monochromatic broadloom, installed wall-to-wall. At that time, improved techniques for keeping households clean allowed homeowners to re-embrace the wall-to-wall carpeting that they had shunned for sanitary reasons several decades earlier.

Despite the trend to modernize, the Austin family continued to add to and maintain their assortment of Oriental rugs in their conservatively furnished home. In the early 1930s they purchased several large carpets and runners second-hand from friends and dealers. Presumably, the movement toward broadloom encouraged the second-hand market in Oriental rugs.

( 1982.7.1008; City of Toronto Collection.)

(Photograph by Neil Brochu)

Torontonians have indulged in an ongoing romance with Oriental carpets for well over a century. The popularity of these textiles traces the path of the social and aesthetic trends of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Despite competing floor coverings and changing tastes from the 1930s onwards, they remain popular and familiar features in 21st-century domestic interiors, attesting to the longevity of these works of art.

In reflecting on this exhibit, we invite you to think about how carpets and other everyday material objects reveal significant details about other time periods and the people who owned them, as well as about social and aesthetic values. We also encourage you to look at your own furnishings and think about how they connect you to a wider world of design and romance, and what they might say about you and your own aesthetic sensibilities.

Further Reading

- Babayan, Levon. The romance of the Oriental rug. Toronto: Babayan’s, 1925. (Available at the Toronto Reference Library.)

- Denny, Walter B. Sotheby’s guide to Oriental carpets . London: Sotheby’s Books, 1994.

- Eiland, Murray L. Oriental carpets: a complete guide . Fourth edition. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998.

- Ford, P.R.J. Oriental carpet design: a guide to traditional motifs, patterns, and symbols . London: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

- Nemati, Parviz. The splendor of antique rugs and tapestries . New York: Rizzoli, 2001.

- O’Bannon, George W., comp. Oriental rugs: a bibliography . Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1994.

- Thompson, Jon. Carpets: from the tents, cottages, and workshops of Asia . London: Laurence King, 1993.

- Train, John. Oriental rug symbols: their origins and meanings from the Middle East to China . London: Philip Wilson, 1997.